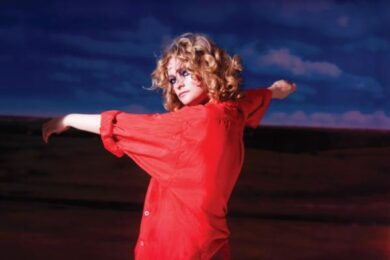

Jack Barnett, with slicked back hair and in a suit made to measure from Shanghai, holds on to a double bass on the Barbican stage. His eyes are sunken, pointed; so much about tonight’s recital of Field Of Reeds seems sunken yet pointed. We’re floating somewhere within These New Puritans, inside the molecular workings of the band. Jack’s compositions are interpreted by the ‘Expanded’ ensemble laid out before us: over thirty players, from violinists and clarinettists to basso profundo singers, who can reach some of the lowest notes in the world.

It is a concert on the edge of something, a set of players out of their comfort zone presided over by a band who, at the end of countless gigs over the years, have looked like they never want to do it again. But something always brings them back.

Aside from some early discrepancies in acoustics, Barnett’s meticulously planned arrangements succeed somehow in letting us in on the secret, opening up Field Of Reeds for us to wallow within its spacial timbres. The affect is aided by Jack’s twin brother (and the band’s drummer) George’s visual direction with Tupac Martir. It is Martir who is responsible for the sudden flashes of light that jolt the audience at the start of the song ‘Field Of Reeds’.

A year ago today on April 17, 2013, tQ’s Luke Turner advised me that the live coverage of Thatcher’s funeral procession made sense if you turned the sound down and played These New Puritans’ as-yet-unreleased album Field Of Reeds on headphones. The ecstatic foreboding and languid, abstract melancholy of the record seemed to expose the event for what it so obviously was: a tragicomic hurrah of British order; obstinate colonial-to-postcolonial Britain reopened like a plague pit, noxious and horrific. Watching it via a live feed on my laptop screen, the combination of the funereal yet ecstatic sounds of the album acted to make the event seem somehow ambiguous, ineffectual, barely there.

Anniversaries are meaningless; circularities and synchronicities are as easily explained away as they are reinforced. But this one feels like something; the collision gives resonance to the way the Puritans have made me feel since I first saw them above an Essex pub in 2005, the way Barnett’s music somehow probes the hidden, finds the elegiac and the sublime in the horrors and scars of southeast England.

These New Puritans speak to Essex, but it’s Essex as adjunct of London, the Thames as slipstream to outside, to the past and the future. When I first heard Field Of Reeds a year ago, it immediately made me think of the container ships of our shared home-town of Leigh-on-Sea near Southend: the way they saunter lugubriously to port and back, as if they were not quite of this world. But as much as I hear echoes of the estuary in the album’s foghorn brass, and the bomb testing on Foulness island in the percussive booms that feature in ‘Light In Your Name’, Field Of Reeds is primarily an introspective work: an internal psychodrama for an atomised and self-involved/inflicting generation, a sonic representation of an inner world. Barnett, alive with his surroundings, travels inward island landscapes and coastlines. He wrote the whole thing in a room and recommends you listen to it using headphones, spurred on by a similar impulse as his beloved Dr Feelgood: compared to the later punk bands, they didn’t want to change the world, they wanted to escape it. Wilko Johnson, Lee Brilleaux and co escaped by getting in a van and touring the length and breadth of the country and then the globe. The Puritans, who used to cover ‘She Does It Right’ and wrote songs like ‘Attack Music’ that sought to shake people with philosophical braggadocio and dancehall-inspired beats, now escape into notation on the page and the possibilities of the studio.

“Her body will be carried by a horse-drawn gun carriage down the Strand to St Paul’s Cathedral.”

At the beginning of the week, Jack Barnett, Elisa Rodriguez (the Portuguese jazz singer and his co-vocalist on Field Of Reeds), and trumpet/flugelhorn player Yazz Ahmed had played a brief set together at the opening of These New Puritans’ Magnetic Fields exhibition at 180 Strand, an abandoned brutalist office building on the edge of a thoroughfare between the City and Westminster, London’s respective commercial and political centres. For a working week, the darkened room was turned into a temporary portal, positioning the Puritans in the centre of a collection of some of the UK’s fellow seekers of their own sonic truth. The group invited Charles Hayward, East India Youth and Scanner to play the Magnetic Resonator Piano, an electronically-augmented acoustic piano capable of eliciting new sounds acoustically from the piano strings, using electromagnets to induce vibrations in the strings of the instruments. Barnett plays the hugely affecting ‘Light in Your Name’, duetting with Rodriguez, electromagnetic mists hissing and fizzing out of the instrument. The song is the first to mark the album out as a record about a relationship and the uncanny power that falling in love can bring with it: You have led me out here (I have led you out here); I can’t lead you back again.

The Strand is formed from the old English word meaning “shore”, referring to the bank of the River Thames which was once much wider (before Bazalgette’s Victorian embankment was built). It is a cord that has fallen into disrepair more than once, before rebuilding itself, renewing again. Large mansions once lined the south side of the street, with their own landings directly on the Thames. The mansions were knocked down and the well-to-do moved away from the riverside toward the West End. Later the street became filled with theatres and shops.

“When Victorian men went out to administer the Empire, or to wage frontier wars with the aid of hampers from Fortum and Mason, they bought their pith helmets, their camp beds, and all the impedimenta of an imperial race in the Strand," wrote HV Morton in his 1951 travelogue In Search Of London, one of the many populist ‘searches’ for a lost idyll that have been published in Britain during the last 200 years. "Whenever [they] thought of London from their places of exile in distant Parts of the earth, it was of the Strand they dreamed in moments of homesickness.”

There is a feeling of the British postcolonial that courses through Field Of Reeds‘ melancholic moments. Cloudy, romantic exploration, filtered through a portentous feeling of dread. “Distinguish melancholy from sadness,” wrote Albert Camus as a command to himself in his notebooks; Field Of Reeds does exactly this, capturing beautifully the general melancholy of England, its present state as much as much as its history; a melancholy bound up between landscape, feeling, geopolitical shifts and the passing of time.

A pertinent moment at the Barbican comes during ‘Spiral’: "This is your guided tour. Exocets towards Stanley. Watch the fireworks from the beach. I’ve got meteors falling to earth. This is your guided tour."

Drums again boom like bombs. Jack Barnett later tells me he sings the line from the point of view of an imagined tour guide on the Falkland Islands, talking rich tourists through a battle recreation scene they watch, champagne flute in hand, from the balcony of a glitzy hotel. He wrote it after watching a documentary on the Falklands War: "I thought it was bizarre the way they were talking about it in this strange detached way, the way people talk about ancient history, like it’s a game or something."

Though the reference somehow seems to connect to the Barnett-beloved Robert Wyatt’s politically charged lament ‘Shipbuilding’, Jack claims that it isn’t an intentional political statement – but it does represent his preoccupation with the ambiguity of established truths, hidden power shifts and motives found between the battle lines of meaning.

The image tickled him, so he put it in. Barnett is a songwriter who, he says, works on blind instinct. It means that often he is at a loss as to what the themes are until later on. The amount of references that the album has to islands and the sea, for example, was new to him until people started to point them out. You can point to the Thames Estuary Essex location of These New Puritans as a possible source for much of tonight’s lyrical and sonic material – the sound of waves lapping on a beach at the beginning and end of proceedings, for example – yet what Field Of Reeds invokes is the power of human feeling. "This is music for music’s sake, but it’s also music about what a person can provoke you to feel, to some extent," Barnett writes in the evening’s programme notes. "I consider this music to be soul music really." In a sense, it is a breakup album. On ‘Nothing Else’, the duet between Rodriguez stops, and it is left to Jack to quietly reflect: "The blue dress. And nothing left. Drift like feathers down. Beneath the rolling waves."

"I don’t want to say goodbye," sings Rodriguez, alone, on penultimate song ‘Dream’. "But as I awake it begins to loosen." As album closer ‘Field Of Reeds’ begins, Martir’s blinding retinal attack cajoles us to take notice of its basso profundo singers, Jack’s gargling phonetic utterances, and the clearer sections of singing: "You asked if the islands would float away, if the stars run through me, like a river, like the air: I said ‘yes’".

These New Puritans’ genius is their will of refusal to dilute ideas in return for mass-market prominence. There was a brief flurry of indignation when Field Of Reeds was omitted from the Mercury Prize shortlist last summer, not least from the band themselves, who posted the not-so-cryptic disembodied phrase "not ‘industry’ enough" on their Facebook page. But it is exactly this failure to connect with the received logic of what ‘art rock’ – or whatever we should be calling it – should aspire to, that has resulted in this very special record of hidden emotional depths.

These New Puritans head to the USA this week. For full tour dates go here