Before we’ve even begun discussing his latest play, Birdland, I explain to Simon Stephens what the term ‘sausage party’ means ("What an extraordinary image," he says), and he tells me he’s thinking of commissioning an award for playwrights who’ve received ten one-star reviews from the Daily Mail. (If you think it can’t get better from here, you’re wrong.)

"It would be a little statue of Quentin Letts with shit coming out of his mouth," he laughs. "And then I’d pass it on to the next writer who got ten one-star reviews. It shouldn’t be mine to keep for life." (If you were wondering, various accusations leveled at Stephens by Letts include ‘not seeming to approve of Mrs Thatcher’ and being ‘sweary’.)

He may jest about being the subject of right-wing vitriol, but Stephens, one of this country’s most prolific playwrights, is currently receiving ecstatic praise for his latest play, Birdland, which is currently showing at the Royal Court. He admits to not having read any of the reviews, and laments the loss of real critical thought about theatre in the broadsheets. "If you look right through the history of art, in all its forms, artists have been dependent on the oxygen of thought that a good intelligent critic can afford them," Stephens says. "Look at Ken Tynan’s role at the National Theatre, or the relationship between NME‘s writers and the punk musicians at the end of the 70s. There can be a real oxygen in those relationships."

But despite his sense that theatre writing is increasingly being pushed out of the mainstream papers, he suggests that theatre has always been a marginal art form. "And actually, it’s fine for theatre to be marginalised, because we’re better than the other art forms, so we can just sit quietly and do better work than you’ll get anywhere else," he says. "It’s a persistent art form which, at the moment, is also remarkably radical." He wonders, though, if his notion of what it is to be radical now is actually quite conservative. He sees his son negotiating between three screens at once, and admits, "inside, I’m going, ‘Turn your fucking screens off and go and read a book!’" but makes an extremely compelling argument that theatre’s importance lies in the fact that it requires thought – something that is becoming increasingly rare in age of twenty-four hour TV, ‘liking’ and ‘retweeting’.

"If you think about theatre, it’s an increasingly rare environment: strangers gather together of their own volition, to share an experience that they don’t fully anticipate until it happens, and it’s happening live in the room with them. You’ve got to turn your phone and your social media off, and sit and share something with someone you’ve never met before. It synthesises both the radical and the ancient; it feels a bit like going to church. And you do something you never do anymore, which is just to turn your fucking phone off."

Birdland doesn’t even allow its audience the luxury of a break in the middle to text their mates. It’s an intense, exhausting and brilliant two hours without an interval. "I like the idea that you should be sticking your head in a bucket of theatre, because at it’s best it should be immersive and experiential," Stephens says. "I nicked that adjective from Sarah Kane. It’s a therapeutic term, and I think theatre can give you the catharsis of imagined experience. "

The bucket of theatre that we are thrown into in Birdland is the world of Paul, played by Andrew Scott (who Stephens describes as "one of the best actors of our time"). He’s a wildly famous musician whose star is ever in the ascendant, and he luxuriates in the dizzying heights of worldwide fame and glory. Or he had been, but now seems lost in a world that is constantly shifting between being utterly intoxicating and totally repugnant – which happens to be a fitting description of Paul himself. Events transform into a rapid downward spiral when Paul sleeps with the girlfriend of his best friend and bandmate, Johnny, and she commits suicide.

For a character who can be cruel, careless, charismatic and spell-binding all at once, I wonder whether Stephens likes Paul, a man who can draw besotted crowds of 75,000 but betray his best friend without batting an eyelid. "I don’t think it’s possible to imagine a character unless you love them completely. And he’s carved out of me. Conor MacPherson said once that when you create a character, there’s an extent to which you’re asking yourself what you would do in that situation. What would I do if I was a musician who made work that appealed to an extraordinary amount of people, and the level of that appeal put me in a position of destabilizing celebrity? Or if I was being encouraged to live under the delusion that I had enough money to buy whatever I wanted?

"So in that sense, I love him completely and sympathise with him massively – while accepting that it’s true what Jenny says to him: ‘You’re behaving like a cunt’. But there’s a difference between behaving like a cunt, and actually being a cunt. But, on the other hand, I don’t really love him, because he doesn’t really exist."

He doesn’t exist literally, but neither does he exist in the world that he inhabits in the play. Paul the rock star is not real: he’s the product of what his manager describes as a "fine and long heritage" of difficult and doomed musicians. Paul the human being is irrelevant, as long as he fulfills the well-worn trope of the dysfunctional rock star.

"Yeah, the rock star becomes a puppet for our own collective cultural imagination. That’s why we rush out and buy Heat magazine: so we can engage and perpetuate the fictional narrative of the famous."

Narrative similarities aside, it feels important that one of the source materials for Birdland was Bertolt Brecht’s Baal. Brecht’s sense of needing to remind the audience that they were watching a performance hits the thematic heart of Stephens’ play: in a world vastly populated by a celebrity culture, we’re not just watching a famous person in a play or a film – we’re actually watching famous people simply live their lives, all the time. And that’s a key to the play’s opening scene, Stephens tells me. "There’s something about the casting of a known actor in that – and this is a play that lends itself to an actor who is celebrated. Remove yourself from the story of Paul and Johnny, and imagine Andrew Scott talking to Alex Price – that whole first scene is just about two actors about to start a play. ‘Have you been here before, have you seen anything here?’ It’s two actors talking about the Royal Court. ‘I like the technicians,’ Andrew Scott is saying.

"’What would you do if I walked out?’ ‘I’d do it without you, they’re not only here for you.’ And that next line, he turns round and says, ‘Do you not think?’, that could be Ben Whishaw or Daniel Mays or Matt Smith, and it would be just as resonant. There’s a level above the story of Johnny and Paul in Birdland which is the story of going to the Royal Court to watch a play about a rock star and watching Andrew Scott in a play about a rock star, that will hopefully invite people to consider the extent to which the lives of the famous has become a kind of puppet show, manipulated by the population at the end of late capitalism."

He pauses for a minute, as if he wants to apologise, and then says, in earnest, "Actually, I really think that. I know it makes me sound really pompous, talking about late capitalism, but actually, I do think that."

Stephens suggests that we need stories about celebrities to help us make sense of who we are. "Narratives unite us in an increasingly atomised and fractured world," he says. It was a chilling coincidence, which Stephens confesses felt "alarming", that the play opened the night after Peaches Geldof died.

He says it’s right to assume that after the play ends, the money machine that is Paul’s career will keep on turning – even though he has been caught doing something that is not only illegal, but that will make the public "lose their taste for him". His management just needs to find a way to market it. "It’s the most hectoring play I’ve written, in a lot of ways. It’s a play about what happens to the human being when we’re defined by what we spend."

Stephens thinks Andrew Scott’s way of explaining the grotesqueness of this idea is brilliant: Scott suggests imagining a funeral eulogy that listed the amount of money that person had earned each year. "It would be abhorrent, monstrous. ‘Here lies such and such – in the last years of her life she was earning over £95,000 a year and had paid off 75% of her mortgage.’ But at the same time, if you raise the question of whether it’s possible to measure a sense of well-being or happiness in ways which are non-fiscal, increasingly people will look at you as though you’re insane."

The relationship between art and money is an important question at the heart of the play. Paul’s tragedy (although Stephens feels it is faintly ridiculous to talk in such terms) is that we never see him making music with Johnny: "It’s tremendously sad. That’s the one thing you keen for," he says, "because you just think, ‘I bet it’s fucking great’."

In the play, Paul describes their music as "twee," and I confess that this makes me wonder (worry, in fact) that they might be something like Mumford and Sons.

"I have no idea what the music is. I suspect they’re a two-piece – just Johnny and Paul. Which makes me think they’re probably a bit like the Pet Shop Boys. The White Stripes were a two piece, as are the Black Keys."

Or Hall and Oates? I suggest.

"That’s fucking exactly who they’re like. It’s Daryl Hall and John Oates!"

At one point, Paul makes a provocative suggestion to a journalist that "this is the best time we’ve ever lived in," an argument that Stephens says is derived directly from one made vehemently in recent years by Steven Pinker.

"We live with the sense that we’re living in the apocalypse. That feeling of the end times gives us a tremendous sense of excitement. But actually, according to Pinker, in comparison to any culture that human society has created, ever, everywhere in the world is better now. His argument is that money has dignified us," he says. "I’m quite interested in that argument – not that I agree with it without reservation, but I like the way that it provokes me into doubting myself. I think it’s very important for dramatists to doubt themselves."

It’s not an idea I’m sure I can get behind, I say.

"Well, that’s interesting isn’t it, because what if it’s true? If you’re faced with proof that life all over the world now is better than it was a hundred years ago, and you don’t believe it, you’re just creating your own reality. Why’s that? Why would you do that?" he laughs. "I completely relate to it, because you read Steven Pinker saying, ‘actually, any other culture in the history of world civilisation, this is better than’, and, intuitively, somebody raised in a kind of social democratic position on the liberal left in the 21st century, bandying around words like ‘late capitalism’ and ‘the end times’, we go, ‘Oh fuck off Pinker, you’re killing yourself, you’re just an apologist for the neo-liberals’. But what if he’s right, actually? And I don’t think he is, but what if he is? I think that’s the difference between a dramatist and a journalist: the dramatist has to embrace uncertainty, and the journalist – you can’t. I can’t fucking finish a sentence without wanting to contradict myself nowadays."

What’s fascinating about Paul is that, although he’s ‘made it’ and lives a blisteringly-paced hedonistic lifestyle, he has completely exhausted human experience. The act of having sex with his best friend’s girlfriend is done in order to experience her experience of the experience: he asks her, "Is this all a little bit exciting?" There’s a suggestion that not only are we living our lives through celebrities – celebrities are also living their lives through us.

"I think we all do that," agrees Stephens. "It’s a phenomenon built on the technologies we constructed to make ourselves feel less alone in a world of catastrophically escalating global population. The fuller a room gets, the lonelier you feel, and that’s happening on a more global level. We feel extraordinarily alone and disconnected from one another, so we construct ways to try and connect with each other, and, actually, they exacerbate the loneliness to the point that the only experiences we live through are vicarious ones. It’s the pornographic age."

In one scene, I say, a fellow audience member seemed to be involuntarily gasping aloud at the things Paul was saying. Why would Stephens want to make audiences feel that?

"I fucking love that. I think the whole point of theatre is to make people different, to change people. Its main responsibility should be that the people who leave the theatre at the end of the night should in some small way be different people to when they came into the building at the beginning of the night.

"They’re physically the same but on a psychological or emotional level, they’re different. That’s the fucking job of art, and in that sense I think it’s an innately optimistic medium. I think it’s also an innately left-wing medium – that’s why there’s no right-wing playwrights – because theatre is built on the idea that collectively we’re more than the sum of our individual constituent parts. It’s a contradiction to neo-liberalist capitalism, where the only thing that matters are individuals."

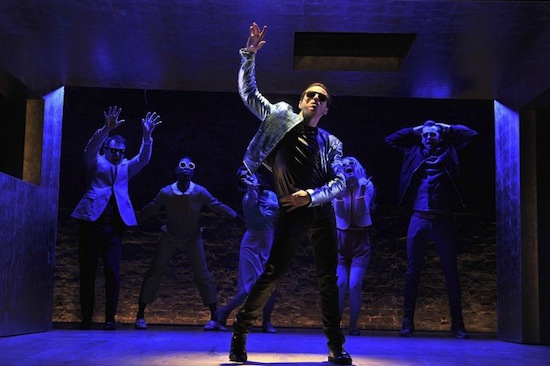

Birdland‘s final moments possess a simple poignancy that actually feel quite epic in their implications. We see Paul in a Bowie-esque stance, draped in sequins and thinking about the possibility of his impending death. Is it a moment of triumph – the rock star eludes mortality, living on forever in a haunted hall of fame full of flawed heroes? Stephens thinks not.

"I’m not sure I completely understand that last moment yet. Every time I watch it, I try and make sense of what that moment’s about. I have an intuitive hunch that it’s related to the notion of death and home. I think it’s the moment he realizes that never dying is an awful thing, that immortality would be a curse. He’s saying ‘I’m never going to get home now’. There’s a great Shangri-La’s song: ‘You can never go home any more’."

And with a glint in his eye, he grins, "I just thought I’d sing that for you. You know, fucking Tom Stoppard wouldn’t do that for you."

Birdland runs at the Royal Court 3 April – 31 May 2014