Claiming to present ‘a new view of the pop-cultural significance of Depeche Mode’, ‘a comprehensive retrospective of the band’ and ‘three decades of music history in a polished synthesis of music and design’, Depeche Mode: Monument (Blumenbar, 2013) promises much. It only partially delivers on that promise, but it is much more than the simple discography it first appears to be, and is both an intensely personal book and one that gives an impression of how defining the band were for a generation of European youth. Born of a collaboration between graphic designer and record collector Dennis Burmeister (the owner of the majority of the objects featured in the book), and historian of youth culture Sascha Lange, who both grew up in an East Germany where the Depeche Mode cult was a significant subculture, the experiences and passions of these two men make for a truly unparalleled publication.

With chapters dedicated to each of Depeche Mode’s studio albums, bookended by sections on their roots in Basildon, Essex, and on the international fan cult that surrounds them, Monument presents literally thousands of obscure pressings, collectable misprints, rare promos and pieces of memorabilia. Vinyl sleeves and labels are documented in minute photographic detail, and this is very much the territory of the serious collector. But if this kind of material has a narrow appeal, it is the weird bits of memorabilia that Burmeister has accumulated that really fascinate. A tongue-in-cheek Mute Records press release for the band’s debut single, ‘Dreaming of Me’, has great poignancy over thirty years later: ‘Aims of the band: to make money and make their mums proud’. The cutting of a Record Mirror live review of an early 1982 gig at Rafters, Manchester, is another gem: ‘Depeche Mode may not be the most remarkably boring group ever to walk the face of the earth, but they’re certainly in the running’, writes a certain Steven Patrick Morrissey. The full-page reproduction of the cover of the November 1984 edition of International Musician and Recording World, featuring the band posing awkwardly around a thundering great Emulator II sampler, is priceless, while the Songs of Faith and Devotion-branded candle and incense burner and Playing the Angel feather boa show the precise calibration of promotional frippery to the band’s changing aesthetic.

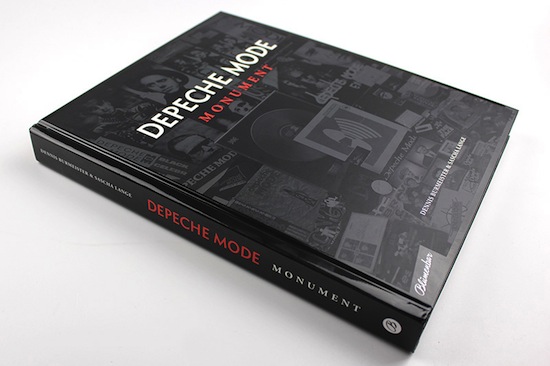

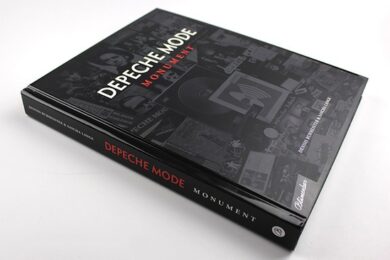

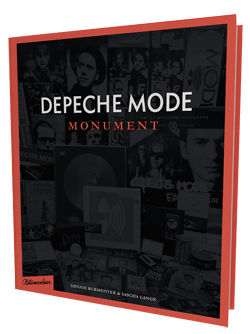

As a text, the quality of Monument varies, and its opening chapter, with its bald statement that ‘Basildon is boring’ as an explanation for the birth of the band, compares unfavourably with Simon Spence’s nuanced, meticulously researched analysis of their genesis in Just Can’t Get Enough: The Making of Depeche Mode (Jawbone, 2011). Monument originally appeared in German, and the central chapters of the book suffer from a sometimes stilted translation and an uneven emphasis due to a lack of adaptation for an anglophone audience, with an inevitable focus on releases from Mute’s German distributor, Intercord. However, the candid interview with Daniel Miller, which is particularly revealing on the early days of Mute (‘I didn’t really know what the fuck I was doing’), and the dry replies from another interviewee, Basildonian friend of the band and sometime roadie Daryl Bamonte, are welcome additions to the English edition. The book is also a truly beautiful object, as sleek black as the band’s own aesthetic, and as tombstone-like as its name suggests (at over 400 glossy pages, it weighs a tonne). Burmeister’s lay out is sumptuous and a great strength of the book is that it amounts to a complete history of the band’s sleeve artwork and broader iconography – a constituent part of their appeal and cultural relevance.

The really personal nature of Monument only emerges in its final pages. It might be expected that Burmeister, the collector, would be the obsessive fan, but he is in fact the ultimate dispassionate completist: ‘Before you start thinking I’m crazy, I’m interested in lots of bands and their vinyls. I’m not their biggest fan who lives in a Depeche Mode museum… I just thought that if I’m going to do it, I may as well do it properly.’ It is Lange, the academic, for whom this is personal, as testified to by his earlier book DJ Westradio (Aufbau, 2007, not yet available in English), reflecting on his Depeche Mode-obsessed youth in the GDR (a period ‘between Playmobil and perestroika’). The touching vignette of Lange’s parents bumping into Martin Gore in Budapest in 1985, when Depeche Mode went behind the Iron Curtain for the first time, and getting an autograph and a hastily snapped photo for their son, both of which are reproduced in Monument, is a microcosm of the fandom of countless teenagers in the Eastern Bloc, and it is the book’s exposure of that fandom in that geographical context that is its strongest element.

‘For East German teenagers, Depeche Mode opened up a cosmos of endless yearning’, the book says. This was a yearning for material goods which were not available on the state-controlled East German market – posters, records, magazines – and that were the physical markers of allegiance to the Depeche Mode cult. While the band’s music, taped from West German radio or copied from originals supplied by relatives in the west, was desirable, when fans from the town of Sömmerda in Thuringia wrote to the band about starting their own fan club (Monument reproduces the letter in facsimile), they asked for autographs, posters and pictures, not recordings. Indeed, the emphasis here is on an unmet, aching demand among teenagers for the artefacts of material culture through which popular cults are lived out. Still, it is fascinating to learn that the hotbed of Depeche Mode fandom in the GDR was Dresden – a broadcasting blackout zone where the basin-like terrain meant that West German radio and TV, and the appearances of the band thereon, was out of reach – being starved of the object of obsession only served to fuel it. The avid fandom of Lange and the completist’s mentality of Burmeister may be seen as born of this starvation – like a ‘waste not, want not’ mentality enduring sixty years after the end of wartime rationing.

Monument‘s photos of eighties East German Depeche Mode fans posing as the band, standing in scrap yards in leather jackets and sunglasses (some of these show a young Lange, although the captions do not let on) are profound historical documents with a vivid sense of place. The authors comment that ‘the grey industrial aesthetic’ that had become a trademark for Depeche Mode by the late eighties was ‘a daily reality for the average apprentice in an East German state-owned Kombinat… The lucky ones who owned a rare, expensive Walkman could practically daydream that they were in a Depeche Mode video all day long.’ But if this ever starts to get close to Commie chic, the most remarkable artefacts in the book jolt us out of any sense of uncritical Ostalgia. Stasi reports on the Depeche Mode fan clubs in Dresden, Zwickau, Leipzig and Karl-Marx-Stadt highlight that in issuing newsletters (‘illegal publications’) and holding fan parties (‘unlawful assemblies’), fans drew the attention of the secret police as potential subversives and were subjected to surveillance and harassment. Here was a generation of young people living under state oppression. Their attitude to that oppression, however, is summed up by a 1988 newspaper cutting reporting a spate of megaphone thefts (the cover artwork of the previous year’s Music for the Masses made these propaganda tools highly desirable adornments for fans’ bedrooms), and the photo of the riot police-issue leather braces requisitioned by Lange (by unspecified means) as a vital bit of Martin Gore-esque sartorial kit. Here is the blithe stubbornness of youth in the face of any obstacle, where even the symbols of subjugation can be subverted and repurposed for liberation.

The future, it turned out, belonged to this generation of German youth, but at the time nothing was guaranteed. When Depeche Mode announced their first gig in the GDR would take place on 7th March 1988, astonishingly arranged under the auspices of the state-run youth movement, the Freie Deutsche Jugend, in an effort to appease the burning desire for Western Pop Music (the state record label, Amiga, had already bowed to pressure and issued a Depeche Mode greatest hits album), ‘no one believed there was going to be a second chance’. As a result, Monument reveals anecdotally, tickets for the concert were painstakingly forged by hand, swapped for state-issue Trabi cars for which there was a 15-year waiting list, or bought for the equivalent of six months’ salary – for fans there was no question of giving up on the dream of seeing their idols live. Ultimately, the story of the Depeche Mode cult in the Eastern Bloc is a story of young people making their lives how they wanted them to be, however slim their hopes for the future and regardless of the plans the authorities had for them – arguably the essential drive of all youth subcultures.

How many more stories are there to be told about this unfathomable passion for a band from urban Essex and the power of Western Pop in the Eastern Bloc? The encyclopedic, picture-heavy approach of the bulk of Monument means that the promised shining of a light on the popular cultural import of the band remains a glimpse rather than a full exploration. Agata Pyzik’s forthcoming Poor But Sexy: Culture Clashes in Europe East and West (Zero, 2014) promises some examination of the Depeche Mode cult in the Eastern Bloc, while Lange’s previous work on youth resistance to the Nazi regime in his native Leipzig would bring a revealing perspective to a fuller published study of this phenomenon, but this remains a history yet to be outlined in full.

With the last German gig of the 107 date Delta Machine Tour already having passed (appropriately enough, this was in DM-obsessed Dresden), the tour has reached its end point, and the band will no doubt disappear for several years. But Monument shows that the Depeche Mode cult has a drive all of its own that operates independently of its focus – as Burmeister says, and Monument demonstrates beyond doubt, ‘the fans clearly show that Depeche Mode are much more than the sum of their individual parts’.

Depeche Mode: Monument is available now, published by Blumenbar