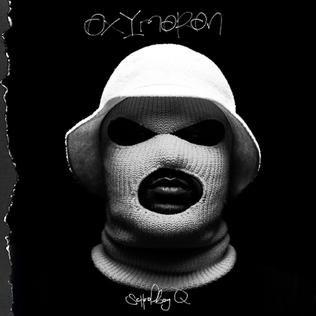

The anticipation for ScHoolboy Q’s latest album has been rumbling on since the critical praise levelled at its 2011 forerunner, Habits & Contradictions. Couple that with a close association with Kendrick Lamar through shared label Top Dawg Entertainment, as well as some particularly savvy marketing and press coverage, and it looks like Oxymoron is set to become one of the more significant hip hop records of this year. Take note, however, that what makes it significant is less to do with any claim on musical or lyrical innovation, and far more tied up with its effectiveness at capturing a set of paradigms at work in contemporary hip hop. Put more succinctly, it’s more sign of the times than Sign O’ The Times.

Opening with the unapologetically self-defining ‘Gangsta’, ScHoolboy Q sets up shop with a piano-heavy beat that conveys both menace and claustrophobia. His voice is distinctively gruff; histrionic in places and gorgeous in others. It compels the listener forward throughout Oxymoron, while also leaving them feeling backed against a corner, Q’s finger jabbing their chest. Thematically the album follows a similar focus to Lamar’s Good Kid, m.A.A.d. City, tales of gang-banging and addiction (in Q’s case prescription drugs) intercut with family concerns. ScHoolboy Q’s daughter Joy features prominently, both as a vocal presence, cover star and object of affection, an innocent figure amongst the bleak and pessimistic vignettes. Particularly effective in this respect is the first half of ‘Prescription/Oxymoron’; built around a Portishead sample, it offers up a detailed narrative of addiction and its reaped deficit, "my daughter calls, I press ignore."

Unfortunately, the second half of the track is a prime example of where Oxymoron repeatedly falls down, its chirruping synthetic hi-hats offsetting a monotonous chorus and verse. The problem is that for all the clever moments – and there are a notable number – the album drags too often. ‘Studio’, for example, is a glossy slo-jam that provides nothing better than a mechanical rut, loaded with casual misogyny. ScHoolboy Q’s issue isn’t so much the content of his story, problematic though it may seem to some listeners. The reality is that Oxymoron fails to develop any of the spark that other, more successful, gangster narratives have. This is no more evident than on ‘Blind Threats’ when Raekwon’s verse drops into the song, opening with "Tuna-fish sandwiches, bread, dry, stinking," before roaming through a flurry of closely observed and evocative imagery. It’s the Wu-master showing exactly where the deficiency of spirit exists in Oxymoron. Too often the lyrics are dry and lacking imagination, or utilise all too familiar gangsta rap tropes, failing to make any kind of impression. There isn’t anything particularly distinct in Q’s lyrics, none of Biggie Smalls’ fatalism, or the back-yard scrappiness of Clipse, or even the Ozymandias-like egoism of Jay-Z. Q unwittingly sums it up best on ‘Canoe Street’, "every last one of us had a pistol in the room," well, exactly.

Musically, Oxymoron veers in quality. There are plenty of strong moments. The synth on Pharrell-produced ‘Los Awesome’ evokes a face frozen in a mirror after the fifth coke bump, suspended somewhere between a kind of greasy euphoria and mortal dread. ‘Blind Threats’ features the neat knock of a drum pattern set against violin and vibes samples, it is easily one of the instrumental highlights of the album. However, too many of the tracks feel forgettable, ‘Hell Of A Night’ tip-taps along without much incident, ‘Man Of The Year’ adopts an empty bassy strut designed to pander to a commercial market that doesn’t exist outside the minds of club promoters. There feels a decisive split between the better, rawer-sounding tracks, and varied attempts to ground Q’s gruffness into a commercially friendly template. Ultimately, nothing hangs together long enough to enable a consistent or enjoyable listening experience.

There is something significant in the swagger of Oxymoron, something that denotes where rap currently sits in its role as clumsy social and cultural barometer. Gangsta rap has historically oscillated between abject nihilism and a grotesque form of venture capitalism. Its protagonists are respectively born-to-die or self-made men, and the emphasis tends to lean one way or another dependent on the prevalent winds within the current socio-economic context.

What is interesting in recent years is how much this polemic has petrified into an anxious rendering of a pure fatalism. ScHoolboy Q seems paralyzed in the belly of something, incapable of agency or change. Where Lamar’s Good Kid, m.A.A.d. City focused particularly on the titular kid, offering a sort of redeemable protagonist in a maelstrom of social pressure and unease, Q is zombie-eyed and scowling, an avatar that assures nothing beyond the mean-spiritedness of the world. It is, in reality, a half-truth, a postured realism that falls into a lazy glorification of the unimaginative, a ground-zero sort of limitedness. Effectively the album embodies what Nina Power wrote about contemporary pornography in One Dimensional Woman: "[That it] is realistic only in the sense that it sells back to us the very worst of our aspirations: domination, competition, greed and brutality." The rush to praise Oxymoron, already a default position amongst many periodicals, is a rush to praise lack: a lack of potential, a lack of hope, and fundamentally a lack to think beyond that which has already been anticipated or allotted to us.