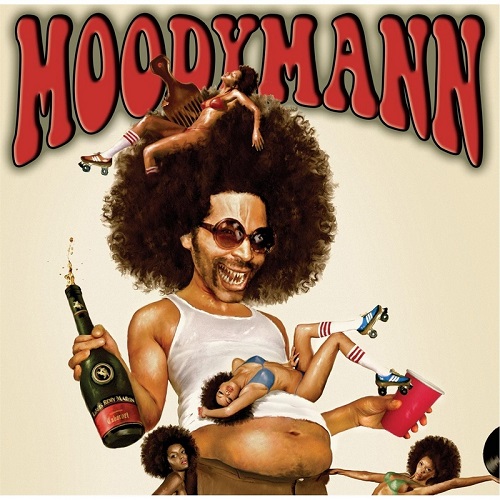

A cursory glance at the cover of Moodymann, the self-titled full-length from the mercurial Detroit producer, connects Kenny Dixon Jr. to the posters and protagonists of the short-lived 1970s blaxploitation film movement. The caricature depicted exudes blaxploitation-era attitudes, with his roller-skating women, liquor and domineering demeanour. For many, this resonance won’t necessarily come as a surprise: Dixon gave his 2010 Red Bull Music Academy interview surrounded by a gang of women, who combed his afro while he spoke and sported his face across their t-shirts.

A closer inspection of the cover, however, reveals this connection to be rather more nuanced. Rather than cutting the kind of muscular, well-dressed figures embodied by Melvin Van Peebles and Fred Williamson, the Moodymann depicted boasts a pot belly, an old white vest and a vampiric grin. Armed with a bottle of Rémy Martin in one hand and a red cup in another, he is both risible and intimidating. He looks like a ghoulish, self-deprecating anachronism, replete with insecurity and cruel intentions. It is this oscillation between pride and self-awareness, extravagance and introspection that, translated into music, makes Moodymann such a rewarding experience, his strongest release since 2004’s Black Mahogani.

Moodymann traverses the jazz-fluting house of "Hold it Down", the sinister libidinal tension of "No" and the Dilla-esque fragmentation of "Girl" with characteristic self-assurance. Disparate elements are drawn together such that they maintain overall coherence while sounding distinct. His inclusion of a slightly reworked version of his acclaimed 2008 remix of Jose James’ ‘Desire’ is a reminder of why it caused such a stir at the time of its release; its use of pointed silences and fractured percussion become incredibly affecting when matched with the simple repetition of James’ "remember" refrain. It’s a powerful example of how house music can use its form and content to articulate complex phenomena, exploring our tendency to sentimentally linger on the past whilst stepping blindfolded into the future.

‘Lyk U Use 2’ is a near perfect pop song, an elegy for a lost lover that delicately plays with its sample to frenetic effect. If songs like these constitute the roller-skating hedonism of Moodymann‘s cover, ‘Sunday Hotel’, ‘Restart’ and ‘Radio’ comprise the sinister corollary. Straddling the line between acid house and techno, the dark side of Moodymann is both unsettling and curiously inviting. The warbling synth of ‘Radio’ plays like a homage to the medium itself, something that has always been integral to Dixon’s work; radio samples have figured as cultural documentation in, for example, his Marvin Gaye tribute The Day We Lost The Soul, among others.

Lost lovers, dying mediums… These themes scattered across Moodymann come to fruition in the closing, eleven-minute, Funkadelic-featuring opus ‘Sloppy Cosmic’. The only explicitly political song on the album, it opens with a gospel organ and sombre chorus: "Oh! Hear my mother call!" When this collides with news extracts about Detroit – "So far this year 128 people have been murdered in Detroit whereas 125 have been killed in Desert Storm … Detroit had the highest murder and unemployment rate. White people have left this city in record numbers…" – the significance of Detroit in Moodymann’s musical thought becomes painfully clear. Following deindustrialisation, his fellow citizens were condemned to the desolation and destitution we associate with contemporary Detroit; we are all too familiar with the images of abandoned factories and $5,000 houses. Any notion of post-Obama progress is rendered illusory by George Clinton’s aphoristic refrain: "Don’t walk so smooth, things don’t seem to have changed that much / Don’t walk so smooth, they’ve rearranged as such".

It is perhaps this mourning for Detroit – expressed as reconstructions of the past through sampling and soul/funk pastiche – that explains the paradoxical figure on Moodymann‘s cover. Whereas the blaxploitation heroes of the 1970s were rolling on the wave of Civil Rights gains, this contemporary blaxploitation hero is a risible figure. He’s fat, his treatment of women is more than outdated, and he’s surrounded by a musical culture dominated by garish EDM and gentrified house. The mastery of Moodymann is its ability to consider and celebrate a rich cultural past whilst simultaneously providing a localised image of what an intimate, cathartic and utopian electronic music could look like. Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song – the 1971 film that gave rise to the blaxploitation subgenre – ends with the eponymous hero escaping the racist police into Mexico. The tragedy is that, a full forty years later, Moodymann finds himself still lamenting the society that Sweet Sweetback wanted to challenge.