David Lynch is more accessible than he’s given credit for. He can be pretty weird by mainstream standards, but he’s often mainstream by weird standards. His harshest critics say that the radically structured Inland Empire is willfully cryptic, or that Mulholland Drive is an obscure salvage job. There’s the lingering accusation that he delights in mystified efforts to find sense where no sense is intended. But earlier films like Blue Velvet are traditionally organized (‘I’m in the middle of a mystery,’ says Kyle MacLachlan at the precise midpoint) and Wild at Heart and The Straight Story come from another writer’s novel and a true-life tale respectively. Their remaining strength resides in first-rate performances by well-cast actors, not from the contrived on-the-fly auterist vision that Lynch is increasingly charged with. But an exhibition of factory photographs? Abandoned spaces are surely one of the most common – one of the most overexposed – subjects in the history of photography. On first glance the display seems altogether too straightforward. Where’s the mystery?

There’s no trick to the exhibition, but technical excellence and a characteristically ominous tone reminding us that Lynch began as a painter, winning an advanced scholarship at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1967 before the eventual $7 million success of Eraserhead. More than eighty snaps are on display – all black and white, all shot using film – from the USA, England, Germany and Poland, taken on trips between 1980 and 2000. We see that space, notionally empty, can contain a sensibility. People talk about Turner’s skies. We can now talk about Lynch’s factories. He’s returning to an inexhaustible realm of fascination.

Although Eraserhead and The Elephant Man were in the can before Lynch thought to photograph factories in isolation, a preoccupation with mechanical, industrial backdrops has been visible since the start. His films are suffused with mechanical metaphors, from the Man in the Planet and his mysterious levers in Eraserhead to the Packard Sawmill in Twin Peaks. (Incidentally the very name Packard chimes with the frequently-pictured Packard Automotive Plant in Detroit, closed since the late fifties and in the words of photographer Zach Fein, ‘set on fire on nearly a weekly basis.’) In Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire the idea extends to the shadowy business kingpins who control the mechanics of Hollywood production, caring no more for their stars than farmers for abattoir cows. In The Straight Story, with Alvin puttering towards Wisconsin on a 1966 John Deere tractor, mechanical industry might be said to literally drive the narrative.

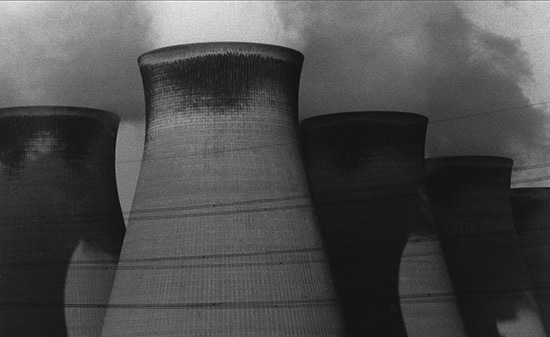

So rather than bubbling up from the ether, The Factory Photographs see Lynch in his element, contributing his vision instead of taking – in the sense of subtracting – photographs. An audience in turn can project or reject their expectations of what an exhibition by Lynch might look like in the first place. In the thermal power factory at Łódź, you might see a dividing line between man-made brickwork and the grassy nature that would reclaim it. In Berlin an angle could be a paused frame from a historical sequence, invisible streams of dusty workers about to emerge with the jittery motion of the Louis Lumière film Exiting the Factory. This being Lynch, you’re more apt to imagine a fade from the turbid skies and rolling smoke of the chimneys to a cloud of ash-grey cigarette smoke drifting from a heavily-lipsticked mouth. He’s consistently praised for creating indelible cinematic images, but in the films he tends towards visceral portraits: Frank Booth as the definitive vision of psychosexual evil, or Rebekah Del Rio expressing the essence of saudade as she sings ‘Crying’ in Mulholland Drive. Preceding that scene, a composite portrait of Naomi Watts and Laura Harring pays homage to Bergman’s Persona, but here in The Factory Photographs location is all. You scrutinize the nooks and crannies fearing the sudden big boo, peering down stairwells and scrutinizing shadows so dark they become substantial, the concentrated blacks of motor oil. Oddly enough this makes the exhibition feel reassuring: you’re drawn towards the light. The only horror is the horror you ascribe, and some people might find terror enough in two of the English photos showing the familiar towers of the Central Electricity and Gas Board before it was quartered and privatized in the early 1990s.

It’s tempting to interpret the photos as mourning the decline of once-great industries, part of a strand expressing the grandeur of the past in America, Europe or the United Kingdom. That’s beginning to feel fairly conventional, a reaction instead of a response. Lynch has said he has pretty much zero interest in the history of the factories, separating his work from the opinion that photography is an essential part of some ongoing project of social reform. Lynch has often emphasized the role of intuition in thinking about art. The Factory Photographs reward meditation, in keeping with Lynch’s devotion to twice-daily practice, the hope being that consideration prevents an audience settling on a clichéd conclusion. Lynch seems to subvert the critical acceptance of the artist’s intention as the standard for evaluation. With gouged walls, damaged passageways and rain mottling the lens many of the images share the ominous qualities of forensic crime-scene photos or first-person victim-views. But here, if the culprits are caught and held to account they’re unlikely to be able to explain why they did it.

One of the bigger questions in the history of the medium is whether the photographer is more important than the photographs. In 1993 Lynch published his first book, Images, the art photos plainly and memorably described by David Foster Wallace: ‘…some of which are creepy and moody and sexy and cool, and some of which are just photos of spark plugs and dental equipment and seem kind of dumb.’ In this case David Lynch, or the set of qualities and themes associated with work by David Lynch, win out. In narrative art the quest for universal qualities tends towards the expression of universal virtues, but in photography there’s more than enough room for universal anxieties around material and mortal decay, degradation and abandonment. Once again, Lynch casts us as detectives, illuminating and animating our nebulous fears. As ever, he shows us the shadows and trusts that we’ll settle the question of whether any subjective horrors hide within. While so many films, photos and commercial images seem to be in the business of keeping thought at bay, it’s a fun and unsettling role to play.

The Factory Photographs appear at The Photographers’ Gallery (London) until March 30. Small Stories runs at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (Paris) until March 16. The Factory Photographs book is published by Prestel, available now