As this occasional series has galumphed along for the past couple of years, there’s been an unintended constant undercurrent. Most of the records I’ve written about have been what one might term "underrated classics" – albums that hit some of us hard at the time of their release, and have remained close to our hearts and our music-playing equipment ever since, but which, in the main, left the rest of the world somewhat unmoved. Perhaps there’s a change in the zeitgeist, or a new mood in the air; perhaps, with the Monty Python gigs selling out in 48 seconds, it’s just time for something completely different. Whatever: this time we’ll

take a look at a record that is the almost diametric opposite of a neglected masterpiece – an acknowledged classic that sold boatloads when new, and remains on many people’s all-time-greatest lists to this day; but which is, at best, a pretty ordinary affair, and at worst, a frustratingly poor record by an artist who, you sense, was capable of making something far, far better.

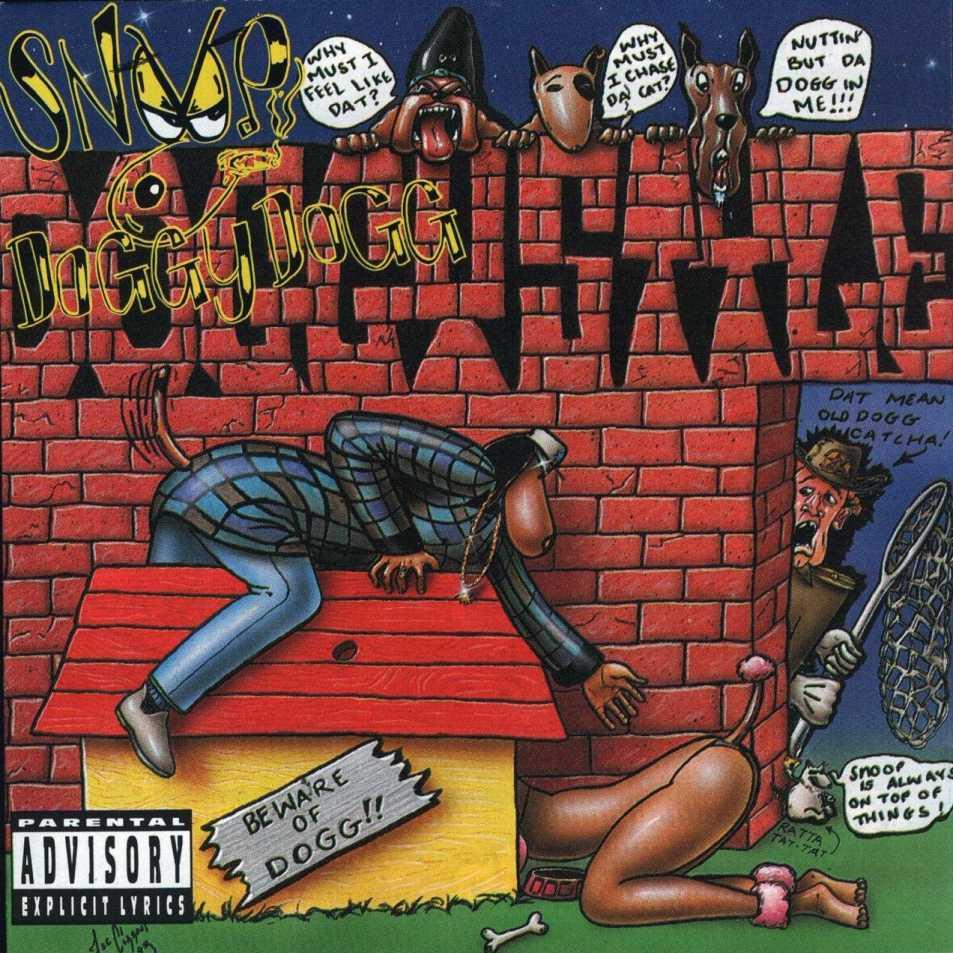

There were things about the-then Snoop Doggy Dogg’s debut that made it a very hard record to love at the time, and which render significant chunks of it, to these ears at least, almost completely unlistenable today. It’s not the production – a step-up refinement of the polished sheen Dr Dre had essayed on The Chronic (the record that, if truth be told, was Snoop’s real debut) which pushed the boat out into expansive, if becalmed,

musical waters. It’s not in the delivery of the raps, with Snoop’s insouciance and half-sung, half-rapped cadence remaining probably the most engaging and entertaining aspect of the album. It’s not even in the lyrics (of which, unavoidably, more later), as variably as they boomerang between the inspired and the reprehensible. It’s more an overarching sense of what might have been, if only the nominal star at the heart of the record had

really been able to properly focus on it.

Unfortunately, for the still-youthful rap protegee, music-making wasn’t really Job Number One during 1993. In a story that has since come to seem almost banal when set next to some of the sagas that later rap icons would find themselves enmeshed in, Snoop spent a great deal of the time when his Chronic tracks were turning him into a superstar consulting with a

high-powered legal team working to get him off an accessory to murder charge. By the time the court found him not guilty, the rapper had completed this album and released it; the notoriety didn’t seem to hurt sales, and indeed the rest of the industry was clearly taking notes, judging by how enthusiastically it embraced hip hoppers who could burnish their "keepin’ it real" lustre with a court-verified rap sheet to go along with their rap records.

It’s instructive to note that 50 Cent was dropped after making a

major-label album that never got released, only for a bidding war to erupt only after he was later almost shot to death; the publicity around a criminal past that had almost caught up with him was fundamental in propelling his second LP to the status of fastest-selling "debut" in US chart history. It’s also worth remembering how Akon saw fit to talk up a relatively modest criminal past (a couple of nights in jail for minor misdeeds) into a story that put him at the heart of a Gone In 60

Seconds-style high-end car-thievery ring, complete with FBI car-chases and months in chokey, all so that (as he would later tell it) he could have a stronger cautionary tale to impart to the kids buying his records, a better narrative with which to tempt them away from a life of crime. The fact that the story helped attract attention and beefed up his streetwise bona fides in the early stages of a career that began with the release of

a single called ‘Locked Up’ were, it would appear, merely minor

by-products of this laudable game-plan.

Regardless of the precedents his situation set, it’s not a stretch (pun optionally intended) to surmise that Snoop wasn’t entirely focused on the business of making an album while he was putting this record together. It’s also important to try to recall the pressure his label, Death Row, brought to bear on its artists by its combination of huge commercial success, lavish and, it would turn out, unfulfillable undertakings to the

marketplace, and the overarching atmosphere of entirely undisguised menace that was a key part of the enterprise’s public image.

Tales to support the latter are legion – many are included in Ronin Ro’s still astonishing book Have Gun Will Travel, and Nick Broomfield’s Biggie and Tupac succeeded in popularising a number of troubling allegations against the label and its infamous boss, Suge Knight – but this writer’s favourite is included in Toure’s collection of music journalism, Never Drank The Kool-Aid. The journalist, in LA to write about Knight’s mentor, Solar Records boss Dick Griffey, gets an interview with Suge in the Death Row offices. An hour-long chat ensues, and all is going swimmingly until Toure asks about an apparent disagreement that was then brewing between the two moguls. Suddenly the atmosphere changes, a man-mountain bodyguard blocks the one doorway out of the office, and Suge, with the by-now terrified journalist’s shoulder in a vice-like grip, encourages him to contemplate, at close quarters, the piranhas in the office fish tank. Finally, Knight rewinds the interview tape, presses play and record, and recites – word for word – the entire hour-long interview, up to the point where the feud had been raised. He then asks Toure if he has any further questions. The journalist says "no", and takes his leave, still shaking.

And then there was Death Row’s, erm, idiosyncratic approach to the marketing of its wares. Most labels would set a release date for a major new album and give every impression of doing their best to stick to it. Advertising space would be bought and interviews and public appearances arranged to coincide: usually, the record would be fairly well in hand, if not entirely completed down to the last paragraph of the sleeve note, before its title or release date were made public. The set-up for Doggystyle had begun – we now can be reasonably certain – before a note was even recorded. Snoop was on the cover of the launch issue of Vibe magazine a good three months before the album wound up in shops, and extensive coverage in other outlets also hit the newsstands long before any music was available to hear, never mind buy. It worked – anticipation was merely heightened; there was no real sense among fans that people were getting tired of the hype and would be bored of the artist by the time his record came out. But it is surely inconceivable that some of this did not translate into pressure that would have been felt in the studio.

Still, by the label’s later standards, this would have been mild: the back cover of this album carries a note saying that the Ice Cube-Dr Dre collaboration, Helter Skelter, was imminent, despite the fact that, in a 2006 interview, Cube confirmed to me that the only track the pair ever recorded for that project was ‘Natural Born Killaz’, which eventually surfaced on the bloated soundtrack LP to what was, in effect, just a long Snoop promo video for ‘Murder Was The Case’. By that stage, over-promising and under-delivering had been added to the Death Row playbook – and those qualities definitely didn’t help. But I digress.

A large part of the snowballing momentum Snoop had balled up going in to November 1993 was down to his starring role on The Chronic. Before its release, he had been part of a group, 213, with Nate Dogg and Warren G, which made demos and achieved something of a buzz around Long Beach – the port city to the south of Los Angeles. Warren had passed a tape to his cousin, Dre, who tapped Snoop for an interesting and well-received single (‘Deep Cover’, the theme song for a Laurence Fishburne film of the same name, in which Snoop’s sing-song chorus introduced the three-digit police code for homicide to rap’s lexicon, the contrast between his delivery and the message as chilling as the vehicular rumble of one of Dre’s more effective and remorseless beats). After The Chronic, Snoop was rap’s biggest new star, and the fact that he was the co-author of much of the material he didn’t appear on as a vocalist himself just served to

amplify expectations for his own LP. His style was new – relaxed and easygoing, genuinely funny – yet he was still a writer capable, on the unarguably moving ‘Little Ghetto Boy’, of using his honeyed drawl to deliver lyrics of genuine power. All he had to do was build on his many considerable and obvious strengths.

There are several moments on Doggystyle where we get glimpses of what might have been. The first single, ‘Who Am I (What’s My Name?)’, is terrific. OK, so it’s just Snoop rapping over George Clinton’s ‘Atomic Dog’ – with that name, and his own fondness for the more laid-back and louche end of 70s funk, he could hardly have resisted the temptation to use it – but nobody ever got rich by overcomplicating pop or overestimating the demands of its market. Accompanied by a fun video which had what was then a pretty big-budget set of digital special effects (not to mention some speeded-up chase sequences directly inspired by Snoop’s favourite TV comic, Benny Hill), it was the perfect first salvo – a marker thrown down, a statement of intent. Here’s a new guy, he’s different, he’s quirky, he’s funny, and you’re gonna like him a lot. It ticks all the boxes and still sounds great today.

‘Pump Pump’, the album’s last track, is pretty sensational too, Snoop trading verses with his cousin (a member of the long-forgotten Dallas Austin-signed teen-rap duo Illegal) over a snarling soundbed made out of rolling bass, old-school-scratchy drums and a single repeated, echoing piano note – the best beat Dre had made since Above the Law’s debut album (and possibly before that, if claims by ATL members and Ruthless Records boss, Jerry Heller, that Dre’s work on that record was more about absorption than contribution, are to be believed). ‘Doggy Dogg World’ is also more than fine, the high-gloss track providing a sumptuous setting for another lyric that, between the phrasing and the delivery, had you believing Snoop could knock ’em out the park like this without really thinking about it. The appearance of soul vocal group The Dramatics on thetrack was a nod to a key influence, as was a fourth standout track, a cover (hip hop’s first) of Slick Rick’s ‘La-Di-Da-Di’, where the tension between the comedy lyric and the uneasily unsettling music really worked. (The ‘Doggy Dogg World’ video included another of the rapper’s touchstone icons – Starsky & Hutch star Antonio Fargas, his 25-year-old on-screen pimp archetype suddenly lent a new lease of life.)

The other highpoint is ‘Murder Was the Case’, a hip hop makeover for the ages-old blues riff about meeting the devil at the crossroads. In this song, Snoop’s bargain with a mysterious higher power isn’t to trade his immortal soul for the ability to rap like a demigod, nor was the song – as some listeners chose at the time to interpret it – a veiled or allusional commentary on his own very real homicide charge. Instead, the narrative has Snoop’s gang-banger lying shot and dying when a mysterious voice

offers him salvation and riches undreamed of, so long as he doesn’t return to violence. In the second verse, the narrator’s life goes swimmingly, but there’s a problem. "They say I’m greedy, but I still want more," he admits. And, without further explanation – the absence of which serves to amplify the inevitability – the next verse finds him in jail doing 25 to

life, listening to the sound of toothbrushes being sharpened into weapons in the cells nearby.

It’s the one track on the record that comes close to matching the impact of ‘Little Ghetto Boy’, and is thus simultaneously the moment you most admire the album, and most despair of much of what its maker felt was acceptable fare with which to surround this genuinely compelling piece of work. Why didn’t he do anything like this elsewhere on the record? If he could conjure such potent visions, write with such breadth and clarity, say so much by saying as little as he feels the need to in the transition between verses two and three, why did he choose to fill up the majority of the album with lyrics that make him sound ignorant? In the back of a car taking him from a London hotel to an interview at a radio station in 1994, he was blunt: saying nothing sells, he argued – and making money is the only thing that matters.

Snoop: "What’s important to me about my music is the clarity and the quality of the music. That’s all that’s important to me."

So what you say in your raps is secondary…

"Some songs are made to just party to. Just dance to while it’s on. Some songs are made to sit down an’ listen an’ see what the fuck I’m sayin’. But not every song on my album is made that way ‘cos I’m not a political person at all. I wouldn’t make no record for mo’fuckers to study, I will write a book for mo’fuckers to study. But music is an art, it’s made to enhance mo’fuckers with. To dance to, or just sit back an’ relax to. It ain’t made to preach – that’s literature, books an’ shit like that."

But don’t you think you’re in a position where, with all these different people listening to your music all over the world, you could make a big impact if you chose to?

"No, because you have to look at it like this: I have not said that shit yet, an’ they buyin’ it, an’ if I do start sayin’ that shit I’m gonna fuck ’em off. Why change what you got goin’ for you? Why would I change this beautiful blueprint I got set up for some bullshit?"

There might be…

"It’s bullshit."

But there might be something you believed in that you wanted to get across.

"It’s all real, everything I write about is all real. My next album might consist o’ that, I don’t know. I’m trying to sell records. I ain’t trying to make nobody happy, I’m just trying to sell records."

Some of the rest of the album is ordinary, in a banal sort of way – bland and only wearying rather than offensively bad. But five tracks and a lot of filler is a poor return for what was supposed to be, to quote a coverline from one of those way-too-early rap mag interviews, "the ultimate bomb". ‘Gin and Juice’ has its admirers, but it’s little more than a riff and a chorus in search of the rest of a song, and its casual misogyny is as unnecessary and disfiguring as it is gratuitous. Tracks like ‘Serial Killa’ and ‘Tha Shiznit’ manage to pass by without leaving much of a trace, while on ‘Gz And Hustlaz’ Snoop’s already repeating

himself, using the "creep through the fog" motif he’d deployed to far better effect in ‘Who Am I’. There’s a sequence in the first verse where the risks inherent in his approach rise uncomfortably to the surface – a line where the laziness stops being endearing and just feels careless. He slides from "I get busy, I make your head dizzy" into "I blow up your mouth like I was Dizzy Gillespie." While the latter is a clever-enough lyric, given the way the iconic trumpeter’s cheeks would inflate like balloons while performing, it’s a non-sequitur in the track – and the

repetition of "dizzy" seems lame. Fair enough, if this was a live

freestyle: you can get away with flowing from one idea into another for effect in that kind of a setting, and if someone is only going to hear it once, the repetition can work as reinforcement. It wouldn’t seem an unusual couplet if this was a demo, the artist rhyming a guide vocal, the equivalent of a songwriter’s "La-la-la"s dropping in as a place-holder until they’d come up with something to fit that part of the song. But this is supposed to be a debut album from a major talent, with advance orders topping the million mark and a multinational corporation (Death Row were bankrolled by the then Warner-owned Interscope) sinking vast sums into a marketing campaign. You’d have thought someone, somewhere, would have had the gumption to turn around to the talent and say, "Sorry, boys, but this isn’t finished."

The nadir, though, is reached early on side two, with ‘Ain’t No Fun (If the Homies Can’t Have None)’. Presumably the 213 associates – the track reunites Snoop with his former bandmates, Warren and Nate – felt this was a harmless lark, a bit of a laugh, nothing to be taken too seriously. And certainly the preamble to the track suggests that nothing it will contain

is going to rise above the level of schoolyard juvenilia of the least appealing kind. But it’s not your imagination that hears malevolence in the way the trio, and fellow-traveller Kurrupt, stick rigidly to a script that follows the title’s concept. In between simultaneously deriding any women stupid enough to actually agree to have sex with them while telling any who do that they don’t respect them for precisely that reason, they

return relentlessly to the notion that merely having sex with one of them isn’t any use at all – the women in question will only prove themselves to be of any prolonged entertainment value (clearly, their only purpose in life) if they are happy to be passed around between all four.

On an album where women rarely appear other than as sex objects, the track rises head and shoulders above the rest and achieves a level of calculated yet pointless venom that still leaves a sick taste in the mouth two decades later. Snoop has since tried to make amends for an attitude to women that has veered between mere "slackness" and – even as lately as the 2004 track ‘Can You Control Yo Hoe’, which did not find him offering advice to owners of unruly agricultural equipment, but encouraging men to hit women who didn’t do what they were told – outright misogyny. In 2006 he published a novel, Love Don’t Live Here No More, in which a Snoop-like teenager is steered onto a more positive path by an indomitable mother, and back in the Doggystyle era he would defend his language by pointing to his female manager as an example of a strong woman he respected. Anyway, even if he has had some sort of epiphany since, the question still remains – what on earth was anyone involved in this track

thinking?

At the time of his first visit to the UK, in 1994, Snoop dismissed objections to the way he spoke about women on this record, reverting to the standard script that when he talked about bitches he only meant bitches, not all women. He also firmly believed – on repeated questioning he was insistent on the point – that the only people who’d get upset about it weren’t the people he was making his music for. There is some mileage in that argument – that the language reflected the small sector of society Snoop represented, and that within those boundaries no offence would be taken. But one listen to ‘Ain’t No Fun’ leaves you with the inescapable conclusion that the only people a record like that could possibly have been designed to amuse are people whose attitude towards women is as beyond fucked-up as its makers – men who use women as sex objects because they want to subjugate them, who want to exert power over women because they hate them; who hate them because they fear them, and fear them because they don’t understand them and aren’t going to bother trying. It’s

not innuendo, it’s not "harmless" entertainment, it’s not even defensible in the way that porn can be: at its best it’s moronic, and at its worst it’s positively evil.

And yet, these days, nobody seems to mind, and the album retains its cachet as a "classic". Q upgraded its initial so-so review with a more enthusiastic one a few years later. About.com says it’s the 19th best hip-hop album of all time. The reliably valueless Huffington Post celebrated the 20th anniversary of its release with an article that claimed that album "solidified itself among the pantheon of hip-hop greatness", while an anniversary interview on MTV revealed that its maker has never actually listened to the record. Neither of those recent pieces – nor, for that matter, the All Music Guide’s five-star write up – mentions the lyrics, which is a bit like writing about a Miles Davis album without bothering to discuss all that trumpet-playing stuff. But that’s 21st-century music journalism for you.

It’s probably fair to say that, with the possible exception of the couple of albums he released during a Neptunes-inspired early 2000s renaissance, no Snoop LP has been better-received or proved more durable than Doggystyle. Yet its impact hasn’t been musical or technical – it’s been political and cultural. That this record would be a turning point seemed certain ahead of its release, but the reason why it has been isn’t the one we’d expected.

Before Doggystyle and during the months it was new, obviously objectionable lyrical content was one of the first things to be commented upon by critics and reviewers – and artists would have had to get used to fielding questions, often repeatedly, about what they meant and why they felt it necessary to say some of the things they were saying. Yet in fairly short order – and certainly by the time Snoop released his belated

follow-up, Tha Doggfather, in 1996 – his fame was of more import than what he was saying in his records. By a combination of his lilting voice and engaging personality, Snoop managed, for the most part, to avoid having to defend the often myopic worldview he continued to espouse in his lyrics. (He was still introducing ‘Ain’t No Fun’ as "one of our Dogg Pound love songs", and clearly relishing performing the song, when he appeared

at the Exit festival in Serbia as recently as 2007.)

It wasn’t just Snoop, either. Perhaps as a consequence of the fall from favour of "political correctness", and the rise of explicit references to hetero male sexuality in other arts, music journalists stopped taking rappers to task when they wrote disparagingly about women. In 1994 I was left in no doubt that my editors expected these questions to be asked and answered, yet by the time of the rise of Eminem and 50 Cent, the issue rarely got a mention – and today, as we have seen, hardly anybody talks

about lyrics in pop songs at all. Part of the reason for this is that people don’t really listen to music any more; they hear it in the background, streamed through tinny speakers or fashion-statement headphones while using their computer or phone to do something else, or they amass it in a vast digital library of soundfiles that get played all the way through once or twice, if ever. But the other main reason is because of events which, if not set in chain by this record, were certainly helped along by its global and considerable success.

Those of us – guilty as charged – who wanted to accentuate the positives back then bent ourselves double making excuses for Snoop, trying to fill the blank spaces his absence of explanations left with grand theories, hoping that there really was something worthwhile hiding behind the nastiness that could permit unconditional enjoyment of the parts of his record that were undeniably great. From the perspective age and (one hopes) some measure of maturity has bestowed, that decision stands

revealed as a desperately poor one. It’s perfectly possible for an objectionable person to make occasionally great art, and it’s just as possible to like the good stuff while emphatically rejecting the bad. Yet history, it seems, has chosen to ignore not just this record’s creative imperfections but also the lyrical and conceptual ugliness it contains and which its success helped persuade others to imitate or condone or ignore – and, instead, we have to buy into the lie that this record is an

unqualified success, a titanic achievement, one of the great artworks of the latter part of the 20th century. There’s some good stuff on it, but much of it is poor and some of it hateful bullshit of the first water – that so many people seem to be OK with denying that is something that should make us all feel profoundly uneasy.