Portrait by Michael O’Neal

Of all the frivolous, vapid and asinine shorthand terms for musical styles to appear in recent times, ‘neo-classical’ (and it’s even uglier cousin, ’post-classical’) has to be the worst. For a musician such as Nils Frahm – to whom the term has been relentlessly applied – the shoe most certainly does not fit.

Foremost, Frahm was born some one hundred years too late to be considered part of the ‘neoclassical’ movement fronted by the likes of Stravinsky and Poulenc. Forced to choose, the dimly clinical term, ‘contemporary classical’ is arguably more apt, yet still lacking. As a musician, he’s part of a more modern phenomenon – a composer who spends as much time adjusting microphones and tweaking digital effects as he does putting pen to stave, and equally finds as much value in improvisation as in meticulous crotchet placement.

Berlin-based, and just 31, he’s steadily garnered a dedicated following in recent years for his expert music. 2011’s Felt was a spectacular example of Frahm’s knack for meticulously recorded and beautifully composed music, exploring the palette of a piano (appropriately muted by the titular material for the benefit of his neighbours). Besides his powerful solo work, he’s participated in multiple collaborations, and in his capacity as a producer and engineer has recorded countless like-minded musicians, friends and composers from around the world.

His latest album, Spaces, sees the intense intimacy of his music translated to a live setting with the help of a grand piano, his felt-prepared piano, several synthesizers, analogue delay and a laptop. Captured across hundreds of live shows over the last few years but distilled into seventy-six minutes, it’s a surprisingly beguiling and gossamer set, spanning Frahm’s career thus far, and amounting to his finest release yet. We caught up with him last week before his late-night show at London’s Village Underground to talk about the influence of ECM records, album covers and the role of the recording engineer.

So, Spaces comprises live recordings, some of which are older pieces – such as ‘Said And Done’ from The Bells. How much did improvisation come into play when these were first recorded and how do you regurgitate them on stage? Do you write stuff down?

Nils Frahm: No, I don’t write stuff down, but I remember well. I was never good at sheet music reading – so classical lessons were hard. I would always listen to the original pieces and then learn it bar by bar, just by muscle memory. The version of ‘Said And Done’ on The Bells for example was created that night. There were two nights of improvising, and that song just happened to be on there, only this one take of it. It wasn’t even something I considered to record twice, it was basically just brainstorming, going with the flow, and there’s something nice about not paying a piece ten times, because then it doesn’t feel forced or stressed.

It then became one of my more popular pieces, and people were always saying, “Play it live, play it live!" So then I had to learn it! So I remember I had to listen to the recording again, and then learn my own piece. So whenever I do an album, in order to play some of it live I need to sit down and really learn it again because most of the songs are just one takes and just improvisations and I kind of like that in the studio, to not ‘work on it’ so you can play it exactly the same. Just a few chords with a rough idea. Over a couple of years of touring, over something like 300 concerts later, the piece got longer and longer and more complicated, and so I thought it would be fun to just give an updated version of the piece and how music evolves when it sticks to you.

Do you ever write notes down though? ‘Hammers’ from the new album seems pretty complex.

NF: It sounds complex, but it’s pretty easy once you know it. The pattern’s always the same, and then you have four notes and the combination of these four notes, I myself transfer to chords. So I play Gm7, I play B6, or I play this chord or this chord [mimes on an invisible piano]. I learned jazz too, so I just think in symbols. Each chord I play is not a bunch of certain separated notes, but it’s a symbol. They could be in any order.

There are several pieces on Spaces that use synths and effects, particularly the second track…

NF: ‘Says’.

That’s the one. That sort of keyboard-based, extended electronic music is something that I associate with Berlin, particularly because of the 70s and 80s Kosmische musik stuff – Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze – and ‘Says’ instantly made me think of that. Is that something you listen to a lot of, or feel the presence of at home?

NF: I love the photos, you know what I mean? When you see the stage of a Tangerine Dream concert, I always had that with the records – I love how it looks to have all the modular synthesizers, and this light show. Then I listened to the record, and sometimes you feel a little bit cheated on. You think, “All that amazing stuff, and this is how it sounds like?” So maybe my version was a little more shaped by contemporary music. We have so many different tastes and flavours of electronic music that our ears have got quite picky, and it’s not enough to just make a synthesized sound in order to make people’s jaw drop. But I think back in the day it was enough. Kraftwerk – it was enough that there was no drummer but you would hear drums, that was revolutionary! For what they had and what they did, they were pioneers and I admire their work, they were hard workers.

Kraftwerk developed their instruments. They weren’t invented, so in order to follow their vision they had to talk to Döpfer (a modular synthesizer brand). This is what I like to do too. I sometimes go to the Apple people in Berlin and try to work on the software a little bit. The track, ‘Says’ is a step back though – what can you do with one delay and an old synthesizer, no computers.

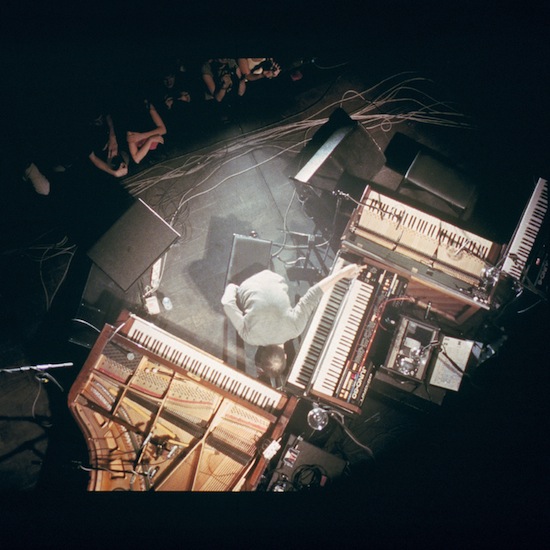

Live photograph by Alexander Schneider

One of the defining characteristics of your recent albums, particularly Felt, has been the inventive microphone placement, and almost preparing the piano. Does any of this happen live?

NF: [Pulls out a copy of the album sleeve – pictured above – and starts pointing at the front cover] So on the left and down we have the grand piano. I take the lid off here so I can put microphones everywhere, and underneath the strings is a pickup like an electric guitar pickup, which makes it much louder than it would usually be just with microphones, and it picks up amazing low end.

This is my small piano [Points to top right of photo], this is where I play the Felt pieces. I carry that thing around, it’s totally modified and miked like on Felt or Screws. [Points to keyboards on the right] This is the Juno I play ‘Says’ on, and this is the old tape delay machine, and underneath is the Fender Rhodes. And I have some volume pedals, one computer which generates reverb, and that’s it. I try to just walk between these things – no Loop Station, no playbacks – I just try to use what I have and everything I create has to be in real time. That’s the limit, and that’s what I try to expand upon. If I would introduce loops or playback it would become infinite.

Is the limitation inspiring?

NF: So inspiring. It’s like you try it every night, again to make it better and better. It’s more like this martial art process. Sometimes I feel like I’m in a training camp and I must please my master, you know? “Today I will nail it!” Believe me, I play a hundred times the song [‘Says’], and the version on the record is good, but others are horrible and just don’t work out. That’s also why I had to record so many shows.

I read an interview saying your father used to work for ECM records. What did he do and how did ECM affect you growing up?

NF: Well my father never met Manfred Eicher [German producer and founder of ECM] in his whole life. He didn’t really ‘work for’ ECM. He was a freelance photographer and the graphic designer, Barbara Wojirsch – who did all the typography for ECM – knew my dad, and she pitched some pictures to Manfred and he liked them. He did one Pat Metheny album, which got widely popular, he did a few more. That stopped in the early 80s.

That inspired my musical career. Because we got all the promotional copies back in the day, so every two or three weeks, we’d get a package with one or two or three new releases. Amazing stuff – Arvo Pärt, Ralph Towner was big for me, Keith Jarrett and the 60 albums he did – I know them all inside out. Even as a child, that was the kind of music I was comparing my music to, so when I’m coming home from school band rehearsals with my tape recorder, I would listen to that and listen to ECM records, thinking, “How do I match that? How can I achieve the same quality they achieve?” It was very obvious to me, even as a kid, that what they were doing is something absolutely breathtaking, in terms of recording, production, playing, the visual part of it, everything. It was brutal honesty, and all connected. The aesthetic of how it feels and how it looks enhances the experience. Before that, covers were mostly ugly except for Blue Note. You’d need to put them face-back if you didn’t want to get distracted. You get some beautiful Chopin recording on Deutsche Grammaphon, and there’s some ugly guy on the front cover with a bad flash photo. Why?

You mentioned Keith Jarrett, and there’s some obvious similarities between some of what you do and what he did.

NF: No doubt.

There are some deeper ones too though – those speedy groups of notes in the right hand for example, or the vocalisations. On Spaces, on the track, ‘Hammers’ you vocalise…

NF: That was a conscious choice though, I think when Keith Jarrett does it it’s not. It just, comes out.

So with you it was a conscious choice?

NF: Yeah. I’m playing every finger as hard as I can, but always when I hit the second finger, it’s the melody, so I couldn’t hit it hard enough to make the melody stick out. So this note needed to be longer and freer, so I thought just sing it.

So which piano players were big for you? You have a very specific sound, as does Keith Jarrett, and it’s not just the nature of the piano, there’s something more…

NF: Yeah, because when you hear three chords of Thelonious Monk, you know it’s Thelonious Monk. For me, it was always the East Coast American jazz of the thirties to fifties that inspired me to find my own particular voice, so you always know. This is Johnny Hodges, this is Miles Davis, this is Bud Powell, and this is Thelonious Monk. This is what they were proud of and this is what they were working on their whole life, to be different from anything else. I really thought that makes sense, because then it’s only you who can create this music. Especially with Thelonious Monk, he got so far out of anything that anybody else did before on the piano that he was widely accepted, even in his lifetime. It was almost clownish, as if he was making fun of jazz. It’s like little jokes sometimes, but it’s so precise and wonderful and emotional still, that I thought I want to achieve something like Thelonious Monk did in his life. I don’t want to be good at everything, but I want to be very good at this one particular thing, which only I can achieve.

You’ve recorded dozens of artists in your studio – as producer, mixer, engineer, what have you – how does this come about typically and what does your role consist of typically? How did the studio start?

NF: I was the guy at school who could make sense out of a mixing board and had this intuition with that. Recording sound was something so magical to me that I didn’t even want to tell my friends about it, [I was afraid] they’d think it was hilarious. I was under my blanket in the night and doing recording tests with tape decks. So it was pretty obvious that I would need to go in that direction. I was always the guy who would make the sound in venues and clubs and youth clubs. I got to know the gear. After a while I was recording and mixing the bands in town in Hamburg, and passing the masters to the record labels. It was so much fun the whole process. Getting the 7" test pressing the first time and it sounded shitty, thinking, "Does it sound shitty?" and the millions of questions – “Why can’t I do the ECM thing”? And then I listened to Radiohead’s Amnesiac when I was about 16 or 17 thinking, ”Why does it sound so good?” I was so fascinated by how it sounded great on a tiny stereo, or on a good stereo system. For me it was more like a transcendental experience to realise that some people have the key to something I don’t have yet. So I got obsessed with needing to know all there is to know about capturing sound.

Do you not feel – when ‘producing’ – that part of your authorship has gone into it? That part of it is yours as well?

NF: I mean, I didn’t do any of the compositions. It’s more just ideas. Mixing is sometimes taking one track out – “We don’t need the shaker here." Or thinking that perhaps we’d need to pitch the whole song down a tone so it would sound better. There are all these little tricks you can help people with. That’s the social aspect of making music and it’s a lot more fun when you’re together with somebody. Being alone isn’t very much fun, and once in a while I like to get together with friends, throw on the tape machine and record something.

The psychological aspect of making a record is vital too – is the light good, does the room feel cosy enough, was the food good, is the performer happy? People like Rick Rubin or Manfred Eicher, the really big producers, they are also psychologists, and if I weren’t a musician I’d have done something with psychology. I’m interested in how human beings react in certain situations, and what music does to people’s emotions. How we can change people’s attitudes with tones. After I’ve played a good concert, people leave the room happy. This is something we can give back to the world. When people feel down and like it’s all going to shit, at least we can give them some music and change their attitude so people don’t think it’s all shit.

That’s something you believe in?

NF: That’s my religion. The only thing we can try is changing people’s attitude, but not with words. I don’t want to be Bob Dylan, I can’t express it through words but I can express it through emotional experiences. All the answers you need to know you have inside yourself and all you can do is inspire these sorts of answers, perhaps by conversation or by music or by looking at a piece of art. I only have one lifetime to do it and it feels way too short!

Live photograph courtesy of Tracy Morter

What did you do before you made music? Have you ever had to just like, work in a shop?

NF: Ja! I think I had like fifty jobs or something, because I was so bad at everything else, and because I didn’t want to do it I got fired all the time. I worked as a postman, in a coffee shop, I was cleaning houses, even toilets, I worked with a lot of places with physically and mentally disabled people, which was actually quite fun – I had all kinds of jobs. When I was 25 or 24, I decided to just make it work with music, so I started doing location sound for movies, or little advertisement clips for horrible stuff. I would take any job that was connected to cables, microphones and instruments. Just making, making and making every day. I made a big step, because when you really take it seriously it takes time, it’s not enough to just mean well. If you want to go somewhere with music, it needs that sacrifice.

Where does the music actually happen? You were saying how the packaging of an ECM record makes you feel, or perhaps when reading an interview? When your fingers touch the piano? When the sound reaches the microphone? Where does it come from? Is it just in the listener?

NF: I think the listener’s the key. The listener’s everything really, because, the physical sensation, moving air and certain frequencies, makes sense and can be understood, but what I don’t understand is how this particular note or that combination makes us feel that way. Why does a dominant chord make us want to get back to the first chord or the sub dominant make us want to go back to the dominant first and then back to the first chord?

Without the listener, it would all be nothing. Musicians, we use something we didn’t create, you know. It’s this big miracle, why is it that moving air does make sound? We use this phenomenon, mostly in a very predictable way. The piano wasn’t invented by me, and the air wasn’t invented by me. I’m just copying what I listened to all my life, and adding a tiny, tiny bit of my stuff.