Starter for ten. Who was it who said "Natural law dictates that each of us be left the freedom to do as we will with our desire, our soul, and our body, as well as with that stuff known as ‘drugs’"? While it sounds like an excerpt from one of Bill Hicks’ routines about the arbitrariness of legislating the ways consciousness might be altered, the answer is actually French philosopher and literary critic Jacques Derrida, speaking in a 1989 interview about the semantic instability of the drugs debate.

It’s Derrida’s own rhetoric, though, which is perhaps most telling here, in as much as it makes explicit a conceptual link between drug use and something called ‘freedom’, a syllogism which has inhered in popular music since at least the 1950s. Rarely has this association been so prominent as in the rock which traces its origins to the psychedelic insurrection of the late 1960s, and the recent renaissance of space music affirms that it’s a belief which still holds firm for many.

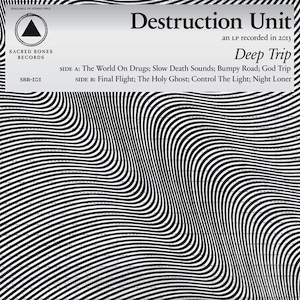

The opening track of prolific Arizonans Destruction Unit’s gauchely-titled new album Deep Trip is called ‘The World on Drugs’, reasonable indication that they’re one of those bands (Electric Wizard spring to mind here) who advocate some form of ‘freedom’ through narcotics. But the record as a whole gives us reason to ask questions about how ‘free’ this kind of music is, or has ever been. The assumption has typically been that drugs, or at least psychedelic drugs, bring about a liberation from the norms of cognition and perception that bears itself out in a tearing-up of the musical rulebook.

Isn’t it the case, however, that much of what has been recorded as an answer to this removal of constraint has actually become a highly regulated idiom? As early as the mid-1980s, space rock had evolved its own subgenre of retro in artists like Spacemen 3 who, for all of their hazy appeal, essentially deferred on sonic (repetition, reverb, drone) and lyrical (hymns to mind expansion) terms to venerable precursors such as the Thirteenth Floor Elevators. Like surrealist painting, which swiftly lost its innervated edge and became mired in a sequence of generic visual tropes, psychedelic rock has all too often foundered on its own freedom and lapsed into cliché.

On Deep Trip, it’s difficult to see how Destruction Unit have made any attempt to disentangle themselves from the past in order to truly embrace a liberation referred to specifically in their press, which speaks of a "spiritual odyssey of sadomasochistic self-loathing with songs about love and freedom". It sounds amazing in principle, of course, but it seems that all that’s really offered is a thematics of unboundedness rather than a practical demonstration of it. The way of refuting allegations of unoriginality in this case will, I have no doubt, be someone pointing out that ‘it rocks’ or, indeed, that ‘it fuckin’ rocks’ – stoner rock having generated its own unfreely free critical vocabulary – and I wouldn’t contest this with much vigour. And yet it doesn’t ‘rock’ as well as comparable contemporaries like, say, Moon Duo or Föllakzoid, both labelmates of DU on Sacred Bones.

For a start, the production is too forensic in its efforts to recreate the cannabinoid claustrophobia of an evening round the bong with strangers. Many bands have made a virtue of this effect, but here it feels almost kitschy, the stentorian, Morrison-cum-Astbury vocals emerging periodically from guitars which skitter between Zeke-esque hyperactivity and chugging dirge. There’s a huge lack of definition, and even with the volume cranked high, the dynamic surge previous albums from the group have led us to expect is absent.

Another problem is that, while the riffs differ from song to song in the sense of the notes being played, they all share the same essential shape. Excuse my rudimentary mode of notation, but a guitar line that goes something like der-der-der-DER-der-der-der-DER-der appears in four or five songs, meaning that Deep Trip struggles to elevate itself above unusually aggressive background music. It’s not rubbish at all – ‘God Trip’ sees DU coming within touching distance of producing the ecstatic, erotic, thanatotic experience they seem to think the album as a whole will deliver – but it does seem to have painted itself into a corner with its reliance on the conventional sounds and images of deathly, druggy rock. In other words, there’s not a lot of freedom to be found here, just a rather abstract celebration of a chemical ideal that never really lives up to it, a ‘Take Me to Your Dealer’ t-shirt of a record. No doubt this is fantastic stuff live, mind.