Few artists have circumscribed the possibilities of their art more thoroughly and with such panache as KRS-ONE. As a teenager, his perspicacity about hip hop and what it might mean was as breathtaking as it was audacious, and in the second decade of the 21st Century he continues to act not just as the culture’s spirit guide and conscience, but as arguably its consummate individual creative force.

High praise? Yes, but not hyperbole. This is an individual who, as great as he is and as confident as he has every right to be in his own abilities, never forgets that his creative achievements are the sum of hard work, application, consideration and concentration – and that means they are within easy reach of anyone else prepared to work as hard and with similar focus or direction. It’s kind of like a superpower: sometimes, you’d swear KRS is clairvoyant.

Example? Well, take one point in 1988, where, having already invented* gangsta rap and foreseen its up and down sides on Boogie Down Production’s epochal debut, Criminal Minded, Kris finds himself in the middle of a rhyme, speculating on hip hop’s potential for longevity, lasering in on its major weaknesses, then lays bare a truth that plenty of people still

haven’t wised up to:

"I’m not Superman, because anybody can

or should be able to rock off turntables,

grab the mic, plug it in and begin.

But here’s where the problem starts: no heart –

because of that a lot of groups fell apart.

Rap is still an art, and no-one’s from the old school

‘cos rap is still a brand-new tool;

I say ‘no-one’s from the old school’ ‘cos rap on a whole

isn’t even 20 years old

Fifty years down the line you can start this

‘Cos we’ll be the old school artists"

‘I’m Still Number One’

For this writer, those lines only started to make complete, crystal-clear sense for the first time when, at a point in the late 1990s, I heard a younger fan referring to Nas as "old school". But Kris had seen the future. In some of his recent gigs he’s taken to doing a freestyle-based routine in which he tells the audience that he’s not just there on the stage in front of them, but he’s also in the hotel after the show, looking back in his mind’s eye to the events earlier that evening, and that this

future self is, in effect, standing in the wings, communicating with the physical manifestation of his spirit that is standing there in the present. It’s poetry and art, so it doesn’t need to adhere to the evidential standards of science – but there’s something real and true and unarguable in the thought that, if you’re constantly thinking about how you’ll view your actions tomorrow, you might stop yourself doing something stupid or damaging or contrary to your principles today. Anyway: here’s

evidence of an artist not just ahead of his time, but with decades of experience of predicting the future. Shit, he might be a time-traveller too, for all I know.

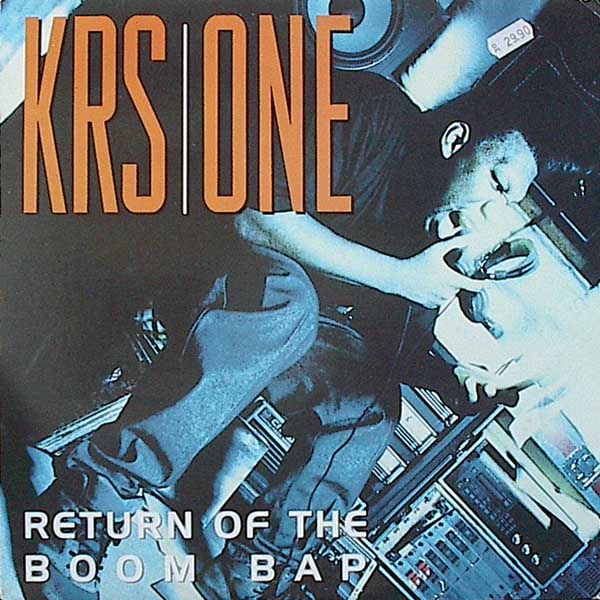

But back to 1993, when a series of tides were beginning to turn. Today’s conventional histories of hip hop will not, in the main, speak of KRS as an old-school artist – he belongs, in the canonical narrative, to the music’s first great Golden Age, the 1987-1992 period where the genre found its voice, hit its stride, became the most important and interesting sound around. The Chronic is the widely accepted endpoint of the Golden Age, for a number of largely agreed-upon reasons, but the one that matters here is the way it turned what had hitherto – despite the occasional hit single – been an underground music into mainstream pop. Within five years we’d have Wu-Tang becoming the first hip hop group to have an album go straight to Number One in both the US and UK pop charts in the week of release; Puffy would shortly have a hand in three consecutive US Number One singles and top the Billboard charts for half a year. Eminem wasn’t that far away. And yet, despite Dre and Snoop, such dominance of the

mainstream was unthinkable when Kris began work on Return Of The Boom Bap, his seventh album (if we include Live Hardcore Worldwide, the first live rap album – and we should, absolutely), but the first to be released under his name rather than that of Boogie Down Productions. He’d formed the duo-led family after he met the DJ and social worker Scott La Rock in 1986 – Scott worked in a homeless shelter; Kris moved in – and he

kept the name, even after Scott’s 1988 murder. To this day, no new KRS album is released without the legend "Overseen by Scott la Rock" somewhere on the package. (As with so much in Kris’s career, there’s an element of prefiguration there, too: Scott’s murder remains unsolved, pre-echoing the same tale that would play out again and again, from Pac and Biggie to Jam

Master Jay.)

Look again at those lyrics to ‘I’m Still Number One’ and consider the lines about lack of belief and fortitude causing rap groups to jack it in – then fast-forward to ’93 and think on Kris discarding the BDP name, and opening what was bound to be seen as somewhat of an under-pressure album after the commercial disappointment of the last BDP record, Sex And Violence, with a song called ‘Outta Here’, in which he discusses why

rap groups don’t have lasting careers at the top of the game. Why did he go there? What was there to gain? Not as much as there was to lose, certainly – but this is an artist who revels in risk-taking, who lives to answer the questions others are too chicken to ask. Half the time you can kinda give those detractors who find him self-defeatingly contrary (and a bit pompous with it) some kind of credit: this is, after all, the man who called for an end to black-on-black crime and the often poisonous posturing and aggression that seemed to course through the 1980s rap scene

following Scott’s death – then, a few years later, claimed absolute justification in elbowing the blamelessly pacifist PM Dawn off a New York stage. "Stop the violence: or he’ll kill you," as a caption to an illustration accompanying an album review in the NME pithily put it. But, to ‘Outta Here’, the matter at hand: what on earth was he thinking?

The name-change wasn’t a rebirth or reinvention: more, really, the sort of thing that happens when a Hollywood studio reboots a film franchise – partly a recognition of the status quo, partly a sleight-of-hand to enable Kris to take his records up a notch. He’s spoken recently – <a href"http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erwJzZxaWXs”>in a fascinating interview published by DJ Premier – of how Sex and Violence‘s comparatively modest sales, and the negative reaction even from fans to the PM Dawn incident, had effectively killed his career; and while he was still shifting enough records to be comfortable for his own purposes, the confidence his label – Jive/RCA – had shown in him was ebbing away. A reset was necessary to reinvigorate the support structures around him: but that need also seems to have helped him find a new path, a new niche. Reconnecting to his past and to the fundamentals of the genre right at the point where it was about to go mainstream, Kris began to believe in the task as not just one of personal importance, but of absolute necessity to

the art form. Within months he started telling interviewers not just that he was doing hip hop, but that he was hip hop: a subtle yet seemingly egomaniacal shift, yet, when he explained it (anyone who is doing hip hop is living hip hop), less a boast than a quasi-religious mission statement. The next two decades of philosophising and theorising take root here: it’s impossible to envisage a book like his The Gospel Of Hip Hop (published in 2009) had he not gone through this period of re-immersion in the culture’s core values.

In any case, BDP had always been a slightly confusing construct: there was Kris and there was Scott, but who else was a member? All those guys on the inner sleeve photo on the By All Means Necessary LP? And if so, who were they all? DJ/producer Kenny Parker, Kris’s brother – he was surely part of BDP; and D-Nice, the teenager who’d had a few words on Criminal Minded, was in the car when Scott was shot, and was embarking on a (partly Kris-produced) solo career, too. Ms Melodie, Kris’s wife, had also signed a solo deal. (BDP as proto Wu-Tang, anyone?) So it was fairly flexibile, but confusing to fans – all without being sufficiently adaptable to allow Kris to work on BDP records with people outside his core crew.

He’d been doing quite a bit of that in the preceding months, too: a track with Tim Dogg, ‘I Get Wrekked’, still stands among his most bravura vocal performances, while his appearances on Shabba Ranks’ ‘The Jam’ and, particularly, R.E.M.’s ‘Radio Song’ introduced him to mass audiences unlikely to have bought many BDP albums. And he appeared on those records as KRS-ONE, not Boogie Down Productions. Add that to his evident desire to work with producers from outside his immediate circle, and the name-change

made complete artistic sense, regardless of any label pressure or

political imperatives. Opening the record with a track analysing failure strategies employed by lesser talents – and doing it in the form of a narrative that began to lift the lid a little on what had gone on behind the scenes with BDP, in the early days, up to and shortly after Scott’s death – well, that was just consummate Kris.

Around this time, he collaborated with Jonathan Demme’s nephew, Ted – the creator of Yo! MTV Raps – on a prospective movie about the early days of BDP. Joe Doughrity, fresh from assisting director John Singleton on Poetic Justice, wrote a screenplay. It was called Wheels Of Steel. HBO were reputedly involved, but the film was never made. Copies of the script – which is a must-read for anyone interested even peripherally in the Kris and Scott story – still exist. The point in mentioning it here is just to reinforce the idea that not only did Kris know about branding and knew how to tell a story – he was starting to place a value on his, and looking for new and exciting ways to tell it.

The step-change that …Boom Bap brought over the preceding Boogie Down Production records is in the production. That’s not to denigrate what had gone before – even the unfairly and widely maligned Sex And Violence had an abundance of material of true excellence, with some genuinely startling moments both lyrically and musically – but as rap was changing, studio styles and techniques were moving on, and Kris knew better than to get left behind. With his stature in the music he could have turned to practically anyone he wanted, but he chose the hip hop purist’s favourite, Gang Starr decksman DJ Premier, as his main

collaborator for this notional debut. (There are five producers involved: one track comes from Norty Cotto, two from Kid Capri, there’s a killer single from Showbiz and, alongside Premier’s five tracks, Kris contributes four himself, with the two collaborating on another.)

Primo was the perfect choice for the central concept Kris was building. Hip hop was entering the Valley of the Jeep Beats, as the notional "band name" of Public Enemy’s DJ Terminator X would have it: room-shaking head-nodders were in vogue, and Premier, who talked of never being sure a beat was ready until he’d road-tested it in his SUV at high volume on the streets of New York, was the king of the style. …Boom Bap, for all its maker’s canny strategising and apparent foreknowledge of how the genre would soon grow, is less a record built to capitalise on that future success, and more about repositioning its maker as the keeper of the true flame. This is an exercise in going back to the basics, and making that move synonymous with authenticity and integrity. In that regard it was every bit as much a trend-setter as Criminal Minded had been six years earlier: soon there would be a retro hip hop bandwagon for nostalgists to jump on, but before then, there was going to be the little matter of the music becoming the biggest-selling genre in the world. Getting ahead of the curve should be no problem if you talk to your future self: but still, this particular piece of brand realignment was remarkable.

‘Outta Here’ and the lushly orchestrated, genuinely moving closing rumination on pop and politics, faith and belief, ‘Higher Level’, stand among Primo’s greatest yet least-heralded productions. Both songs are less the work of a studio craftsman than an alchemist. The former adds a jazz double bass to a beautifully looped, meticulously crafted, cleverly short sample from ‘Funky President’ in which the horn stab from the

original song appears almost as an echo of itself – another ghostly premonition. It’s the perfect undercarriage for a lyric dark as coal and bleak in portent. By contrast, ‘Higher Level’ takes a thematically unpromising base metal – a cut from Gene Page’s soundtrack to the blaxploitation horror spoof Blackula – and turns it into an exultant and genuinely prayerful piece of melodic yet hardcore hip hop. Of course, the space Kris insists on building into the song is a vital part

of making it soar – the first lyric doesn’t arrive until towards the end of the second minute, with an unrushed emcee seeking to calm his listener and relax into the mood. Regardless of how it works it’s still a remarkable track, a rare moment of real reflection in a genre that usually stresses machismo and chest-beating.

The other thing that’s striking about …Boom Bap is the way that it’s only those two songs, at either end of the record, that don’t feature some element of reggae or dancehall. How conscious a decision it was to bookend a ragga-rap album with two hip hop tracks is moot: but that’s what happens. Dancehall was a natural step, and a long-extant part of Kris’s musical armoury (‘9mm Goes Bang’ and ‘The P Is Free’, from Criminal Minded, stand among the earliest attempts at melding hip hop and ragga, which of course share a common root in the Jamaican dancehall tradition). But he hadn’t put it front and centre to this extent before, and he wouldn’t do so again. Even the rock-hard second single, ‘Sound Of Da Police’ – which remains a key part of every KRS gig, and, ‘Step Into A World’ notwithstanding, is probably his best-known track – finds him riding Showbiz’s inspired Grand Funk Railroad-covering-the-Animals loop in a shouted cadence that comes straight from the dancehall, and dropping in and out of patois as he goes.

Yet perhaps just as surprising is the fact that you can listen to the album a hundred times and never think of it as a reggae record: Kris clearly saw, heard, and felt, in this outsider music, a means of giving hip hop back some of its original spike and bite, so the style is subsumed into a hip hop mode of working. Ragga was then the music generating shock and controversy, albeit hardly in the most laudable of ways (the previous year, a reissue of Buju Banton’s hideous ‘Boom Bye Bye’ had turned the music into the most divisive genre in the world, and its defenders were increasingly regarded as reactionary apologists, if not outright bigots).

And yet, more than any social or political or

those-who-are-not-with-me-are-against-me resonance, what KRS found in dancehall was a sound where a stripped-down aesthetic still prevailed. Hip hop had, by and large, abandoned its early bass, snare and 808 minimalism of the start of the Golden Age – a string of records, Criminal Minded key among them, had introduced the James Brown-centric funk sample sound, and the melodies those musical fragments contained, to the genre. Return of the Boom Bap, then, was an attempt to reset the

clock – to go back to the essence of beats and rhymes, and remind both dedicated fans and curious outsiders that a cute lift from a recognisable and unexpected musical source wasn’t what hip hop was all about (not that there was necessarily anything wrong with that), and that, ultimately, the worth of an emcee can only be judged by their lyrics and their skill on the mic. "Boom, bap, original rap," as the title track puts it: "Refreshin’ when you hear it – real reap is all that."

So the lion’s share of the record isn’t about the ‘Outta Here’

storytelling or the ‘Higher Level’ philosophising – it’s a red-hot throw-down, a dazzling display of the art of rap. You can drop the needle pretty much anywhere on the album and hit a couplet that astounds. Crucially, it’s not so much about the writing – though that’s strong throughout too – but the performances. Even something self-evidently "just" an album track, like ‘Mortal Thoughts’ (though, perversely, chunks of the song appear in what is nominally a video for ‘…Boom Bap’, which

was released as a third single but with a promo that’s really more a four-minute advert for the album as a whole), finds Kris unleashing a vocal blitzkrieg. Written down, "any rapper can be a decapitated rapper/now what’s the matter?" has a certain frisson, but to hear it rat-a-tat-tatting from his mouth at double, triple, possibly even quadruple time, is to bear witness to the most emphatic kind of lyrical assault.

It’s a cheeky record, too – from the Bryan Adams reference that opens the title track (well, he had interpolated Billy Joel on ‘Criminal Minded’ too, so he had previous), via that

wry punchline – you can almost hear his head-to-one-side "gotcha!" grin – to ‘Sound of da Police’s comparison between police and plantation overseers ("they both ride horses!"), to the outrageous three-minute extended metaphor that is ‘I Can’t Wake Up’. Plenty of rappers have talked about dope in their records, plenty too have essayed comparisons between stylistic potency and the effects of high-grade weed: but nobody else ever

claimed, through the device of light-hearted metaphor, to be the fuel that gave a string of illustrious named contemporaries their inspiration. Well, none that got away with it, anyway. This was something only Kris could do: only his formidable talent, hard-earned reputation and his status as one of the few whose work consistently enlarged and defended hip hop as a culture would cause the other lions in the hip hop jungle not to challenge

him for the position at the head of the pride. As the man says: "you never will conquer the champion."

It’s a great record, one of his very best, and resuscitated his career despite – as he points out in that 2012 interview – not really selling any better than Sex and Violence had. It began a triptych of three great albums under his solo name which re-established KRS as the quintessential emcee, the hip hopper’s hip hopper. The self-titled follow-up might not be the most consistent release of his career, but it contains three of the best tracks he ever made – ‘Rappers R N Dainja’, ‘MCs Act Like They Don’t Know’ ("If you don’t know me by now, I doubt you’ll ever know me/I never won a Grammy, I won’t win a Tony") and ‘Ah

Yeah’ – while ‘I Got Next’ put the keystone in place at the top of the edifice he began building on this record. With ‘Step Into A World’, Kris achieved everything he threatened and promised here: he had taken the fundamentals of hip hop culture, in all their rawness and authenticity, refused to compromise on anything, never dumbed down, and still had a worldwide pop hit with it. He could have quit right then and nobody could take anything away from him: that he has continued to make records which confound and delight without ever stopping being true to who he is and the art form he is inextricably bound up in is something we can only marvel at and continue to be grateful for.

* Yeah, I know; Schooly D, and so on. But ‘9mm Goes Bang’ was the template everyone built on, even though most of them didn’t think to include the morality-play elements that made the song so memorable and successful.