Back in 1988 when television broadcasting after midnight was still a novelty rather than the norm, Joe Strummer found himself sat on the sofa of the studios of Night Network, a late night magazine show, and subjected to an interview that challenged the integrity of The Clash in light of the release of their first retrospective compilation, The Story Of The Clash, Vol 1. Surprisingly, for a band that changed so many lives and altered the perception of what rock music could be about, The Clash’s stock, just three years after they’d ground to an ignominious halt amidst a new line-up, internecine power struggles and a dog of album that was to be their last gasp in the shape of Cut The Crap, was at an all-time low. Yet despite their status as yesterday’s papers, the very notion of a compilation album from a band built on integrity and rebellion was still enough to raise the hackles of anyone who’d been touched by their music. Surely this was just another case of turning rebellion into money?

“No, I can’t see that at all,” countered Strummer. “It’s just a retrospective. You can buy into it or ignore it.”

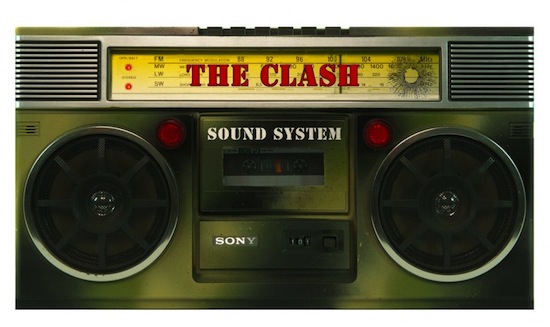

So here we are again, 25 years down the line since that interview and facing the release of Sound System, an impressively constructed box set designed by former bassist Paul Simonon to resemble a camouflaged ghetto blaster. Housed inside are re-mastered editions of The Clash’s first five studio albums – The Clash, Give ‘Em Enough Rope, London Calling, Sandinista and Combat Rock – as well as a host of extras including singles, b-sides, unreleased tracks, a DVD, rehearsal takes and live recordings. And that’s before we get to the poster, dog tags, stickers, badges, a notebook and reprinted editions of fanzine the Armagideon Times. But, in act of revisionism and airbrushing that Uncle Joe Stalin would’ve been proud of, no sign of that deservedly slated final album.

But with a price of around the £80 mark, and coming from a band who famously kept record and ticket prices within the financial reach of their fans – double album London Calling retailed for £5 on its release in 1979 while its follow-up a year later, the hefty triple album Sandinista! was pegged at £5.99 – as well as re-releasing and re-mastering the albums in the closing overs of the 20th Century, the question remains of who this box-set is aimed at. In these tough economic times it seems unlikely that a new generation of fans will be willing to fork out the asking price which, given the still-relevant messages contained within these grooves, is a crying shame. And yet for a total of 11 CDs, one DVD and an excellent re-mastering job by guitarist Mick Jones that breathes new life into this material, this still represents good value for money if you’ve got that much to hand. So while you might not buy into it, ultimately this is music that shouldn’t be ignored. Even from a distance of thirty-plus years, The Clash is as relevant, vital and important now as they were then. Just stop to consider the evidence.

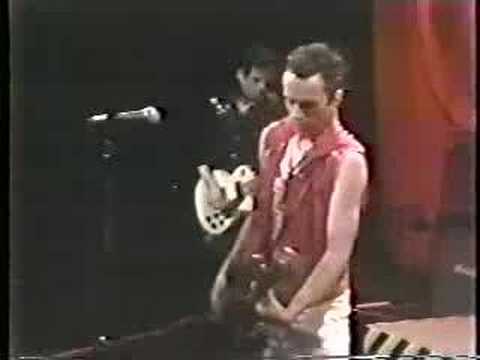

This writer’s first meaningful encounter with The Clash occurred late one night sometime in 1980 thanks to a borrowed video cassette of the Concerts For The People Of Kampuchea aka the Rock For Kampuchea gigs that had been held at the Hammersmith Odeon the previous December. Spread over four nights and organised by Paul McCartney and the then U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, the gigs were put together to raise money and awareness for the victims of the legacy of the despotic Pol Pot and the aftermath of the Cambodian – Vietnamese War. In a pre-Live Aid era, the impressive line-up featured performances from established acts such as The Who, Queen and Wings as well as a guest appearance from Robert Plant who joined Rockpile for a spirited blast of Elvis Presley’s ‘Little Sister’. Among the current crop of bands that had survived punk’s seismic big bang were The Pretenders and Elvis Costello and the Attractions. Added at the last minute to open up for Ian Dury and the Blockheads on the second of the quartet of gigs on December 27 were The Clash.

With only one clip broadcast – a cover of Willie Williams’ reggae classic ‘Armagideon Time’ – it’s difficult to know what the rest of the set, drawn heavily from the then recently released London Calling, was like but based on this one intense excerpt it makes one yearn to see the rest of the gig. With the stage shrouded in near darkness, a single spotlight illuminates frontman Joe Strummer. Dressed in dark jeans and a black and white rockabilly shirt, Strummer holds centre stage with a performance that is by turns passionate and utterly compelling. His eyes wide open in a manic stare and his body barely concealing the electric energy that he’d expend at every Clash gig, Strummer means every word of the number, a song that’s the most poignant over the four nights: “A lot of people won’t get no supper tonight/A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight…” Then, taking a breath and closing his eyes, Strummer allows the sheer weight of the lyrics to rest on his shoulders as he considers their importance. This isn’t mere singing but a channelling of pain and suffering through song and articulated via a performance that grips from the first beat to the last.

Finally plugging in his white Telecaster to play rudimentary chords and clipped rhythms, Strummer gives way to his band mates. Bassist Paul Simonon holds the low-end down with conviction and feeling as he locks in with Topper Headon’s incredible time keeping. A drummer with an ability to apply his huge talent to almost any kind of music, Headon’s beats rise and fall to maintain a sense of drama throughout. Over at stage right and obscured by shadows stands guitarist Mick Jones, his fluid runs floating in and out of the song and never once threatening to overshadow his bandmates. Even from the limited medium of an early 80s television screen, the power of the song and performance slowly hooks and reels me in like a fish swallowing tempting bait. This is something truly special and its power remains undiminished over the passage of time. That night my teenage self was captivated by a band that would help change my life and thousands others in more ways than one.

If any one performance captures the sheer essence of The Clash then this is it. Here is a band that, within the limited confines of a rock & roll quartet, uses the medium to tap into new musical territories that will turn a generation of teenagers onto genres that had been beyond their knowledge while speaking of and to the dispossessed, the alienated and the marginalised. This is pop, in its widest sense, which has something valid and vital to say. To listen this collection of music is to be once again reminded of a time when music was something that could be truly subversive as the messages that summed up the realities of thousands of fans appeared in the charts as an antidote to the asinine dross that filled the airwaves like so much soma. It also serves to highlight that, in our current time of political, social and economic crisis, so few bands are prepared to tackle these issues head on anymore.

Of course, it can be argued that rock & roll does little to change the world but those holding this viewpoint are misguided at best and dangerously naïve at worst. Though the wider world may remain unchanged, songs such as ‘Career Opportunities’ which takes a razor sharp scalpel to the meaningless and alienating jobs that are forced upon people – “The offered me the office, offered me the shop / They said I’d better take anything they’d got / Do you wanna make tea at the BBC? / Do you wanna be, do you really wanna be a cop?” – do much to change the world inside the heads of those listening to it.

Unlike many of their contemporaries, The Clash were cut from a very different cloth. While punk attempted to draw a line in the sand between the perceived failure of the hippy dream and the here and now of a grey, hopeless mid-70s – a time of economic instability, social unrest and a country that closed its shutters at 11pm every night – The Clash, more than any other band of the time, mainlined a lineage that harked back to the 60s. Sure, The Sex Pistols dredged up enough material from that much debated over decade to bulk out their set – mangled and subverted readings of The Monkees’ ‘Stepping Stone’ and The Small Faces’ ‘What’cha Gonna Do About It’ were regular fixtures in their set – but The Clash tapped into the protest music of that decade rather than pop.

This was hardly surprising given that Joe Strummer came of age in 1968, the year of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Street Fighting Man’, the violent anti-Vietnam protests outside the American embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square, the riots that spread throughout the major cities of Europe and America and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and Robert Kennedy. But there was more, too. Strummer’s tastes were also informed by the raw rock & roll of The Kinks and The Yardbirds as well as the form’s originators in the shape of Bo Diddley and Eddie Cochran among many others, all of which helped mould him as he made his way though the pub rock scene of the mid-70s with The 101ers. Guitarist Mick Jones’ first album purchases were Smashed Hits by The Jimi Hendrix Experience and Cream’s Disraeli Gears before discovering Mott The Hoople and New York Dolls’ first album. Growing up in Brixton, South London, bassist Paul Simonon was seduced by the sound of reggae from an early age and its influence on him and the rest of the band was keenly felt throughout their career. Elsewhere, drummer and jazz fan Topper Headon had cut his chops playing with a variety of R&B bands.

The Clash betrayed their influences as early as ‘Jail Guitar Doors’, the b-side to their fourth single, ‘Clash City Rockers’. In the supposed era of punk’s Year Zero, here was The Clash lamenting the fates of jailed former MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer (“Let me tell you ‘bout Wayne and his deals of cocaine”), erstwhile Fleetwood Mac guitarist Peter Green and Rolling Stones founder Keith Richards. They may have sung, “No Elvis, no Beatles or Rolling Stones in 1977” (‘1977’) – again a lament, this time against the lack of urgency in rock & roll in desperate times – but The Clash plugged in directly into music that observed and commented on the social injustices that carried on throughout the decades.

If anything, Sound System displays a band that carried on a tradition of storytelling that had started with the folk movement. These were musical communiqués in an era before the mass communication that we enjoy and abuse today. But even as early as their eponymous debut album, The Clash were already pushing beyond the confines of punk rock and in so doing, more than any other band before or since, turned on a generation of young music fans onto music that they perhaps weren’t aware of. Their tackling of Junior Murvin’s ‘Police And Thieves’ was a bold move and one that, whilst paying off handsomely, showed a band that learned from and employed many of the dynamics of reggae. ‘White Man In Hammersmith Palais’ found The Clash moving further into that direction as they displayed a lyrical and musical maturity that overtook their debut and many of their peers. It was a move approved of and acknowledged by Bob Marley on ‘Punky Reggae Party’ (“The Jam, The Damned, The Clash/Wailers still there/ Dr Feelgood too… No boring old farts will be there”) By the time they reached their milestone album, 1979’s London Calling, The Clash were equally at home tackling classic rock & roll (‘Brand New Cadillac’), soul and jazz (‘Jimmy Jazz’, ‘Hateful’) and reggae (‘The Guns Of Brixton’, ‘Revolution Rock’) with equal amounts of conviction and passion whilst pointing eager fans in the direction of long-lost rocker Vince Taylor as well as reggae artists such as The Rulers, Danny Ray and beyond.

The much-maligned Sandanista! – a 36-track sprawl spread over three slabs of vinyl (here over three CDs) that increased sympathy for the concept of record company control – did much, to its credit, to again introduce new musical forms to open ears. Released in 1980 and largely recorded in New York, the album finds The Clash tuning in to the nascent hip hop scene emerging from the Bronx with ‘The Magnificent Seven’. Remixed, the track dominated The Big Apple’s airwaves as black radio stations put it on heavy rotation. Indeed, The Clash were so smitten by hip hop that they personally invited Grandmaster Flash And The Furious Five to open for them during their 17-date residency at Bond’s International Casino in New York’s Times Square in the summer of 1981. Similarly, its follow-up, 1982’s Combat Rock, found The Clash delving further into dance rhythms and funk and scored a surprise US Top 5 hit with ‘Rock The Casbah’.

While this kind of eclecticism is now common currency among many British and US bands in a post-ecstasy world, The Clash truly blazed a trail that simultaneously remained rooted to their original punk ethics whilst pushing the horizons of both themselves as musicians and those of fans. Not everyone approved, of course, but for those who stuck along for the ride, the rewards of new sounds, new artists and new ideas were rich and tremendously rewarding.

It’s often been said that pop and politics don’t mix and the history of pop is littered with the debris of those that have tried and failed (witness Culture Club’s ‘The War Song’, The Cranberries’ ‘Zombie’ or Simple Minds’ ‘Belfast Child’ among many others for evidence) but it was The Clash that turned the nihilism of The Sex Pistols’ cry of “No future!” on its head as they declared that the “future is unwritten” by turning their attention to social injustice, racism, unemployment and geo-politics. If their debut album was a righteous howl of rage from the depths of disenfranchisement, they’d developed a more sophisticated form of communication by the time they reached London Calling. The opening line of ‘Clampdown’ – “Taking off his turban they said is this man a Jew?” – is at once inciteful and grimly hilarious as it mocks the ignorant knuckleheads at the heart of nationalist movements the world over. Depressingly, it’s still relevant over 30 years since Strummer barked those words out. Similarly, ‘Know Your Rights’ – the opener and lead-off single from Combat Rock – sounds like it could’ve been recorded yesterday: “Murder is a crime / Unless it was done by a policeman…” will be familiar with anyone who watched Ian Tomlinson’s fate on their TV while “You have the right to food money / Providing of course / You don’t mind a little humiliation, investigation…” strikes a chord with anyone who has had to or does sign on every two weeks.

Aligning themselves with the Anti-Nazi League, their participation in the Rock Against Racism in London’s Victoria Park in the spring of 1978 showed The Clash emphatically nailing their colours to the mast. Joined by Buzzcocks, Steel Pulse, X-Ray Spex and Sham 69 among others, the concert was the culmination of a march of 100,000 people determined to show their opposition to the National Front and similar groups. Again, this was a brave move at a time when racist imagery and language was the norm on the TV in the form of shows such as The Black And White Minstrel Show (amazingly, a show that didn’t disappear from the airwaves until 1978) as well as playgrounds, workplaces and pubs up and down the country. Additionally, the National Front and other far-right groups were actively recruiting at gigs, football matches and other social gatherings while hushed mutterings were heard of a proposed right-wing coup from deep within Establishment circles. If any rock band caused a generation and those that followed to think about how friends, workmates, neighbours and community members were being treated then it was The Clash. Indeed, it was The Clash that first took The Specials – a band that truly expanded on those ideas and took them to a wider audience – on the road to open up the Out On Parole tour in 1978. When Joe Strummer, speaking in 1976, stated, “I think people ought to know that we’re anti-fascist, we’re anti-violence, we’re anti-racist and we’re pro-creative. We’re against ignorance” he clearly meant this as much as rocket up his own arse as much as the backside of complacent and bloated bands.

Of course, all of this could have consigned The Clash into the category marked “worthy-but-dull” if (a) the music wasn’t brilliant – which, in the main, it is – and (b) they weren’t such a damn fine live band. This writer can attest to their live excellence having a caught a gig by the post-Topper line-up on their Combat Rock promotional duties but for those who missed out there’s the live DVD contained in Sound System. Culled from early footage by directors Julien Temple and Don Letts, the live extracts show the band from its earliest incarnation to a magnificent beast firing on all cylinders in New York in 1981. What’s immediately apparent throughout these performances is the best three-man frontline since The Beatles. Though Joe Strummer frequently takes centre stage vocal duties with his ever – ahem – strumming right-hand and bouncing electric left leg, the visual aspect of The Clash is completed by Mick Jones, a guitarist incapable of standing still as he bounces across the stage and busting some of the best rock moves ever seen whilst coaxing a series of snaking and punctuating lead and rhythm breaks. To Strummer’s left is Paul Simonon, his bass nearly at his knees, exuding cool and exuberance in equal measure. Even Topper Headon offers flashes of visual brilliance thanks to little touches like a water bottle strapped to his cymbal stands.

The early part of The Clash’s visual aspect can be attributed to art-school drop-out Simonon who took to adorning Jackson Pollock-inspired paint splats across their guitars while adding stencilled messages across their clothes, a move later adopted by Manic Street Preachers. By the time of London Calling the band added quiffs, suits and biker boots as they mixed and matched any number of classic looks like a summation of all the youth cults that had gone before them; through the medium of fashion, this a was band that sought to unite the tribes rather then drive them further apart.

But crucially, in a live context (as much as their recorded output), this was a band that wouldn’t – couldn’t – stand still. The sense of energy and electricity is palpable from these recordings and they still act as an antidote to those bands standing around on stage staring at their shoes as if they’re embarrassed to be there. The Clash just would not let up and this energy fed their audience who in turn sent it back to the stage to create a form of perpetual motion that led to a mutual feeding frenzy.

Not that The Clash was entirely free from fault. Their tendency for self-mythology – ‘The Last Gang In Town’, ‘All The Young Punks’ and ‘Stay Free’ among many others – often grates. The creation of myths is best left to others but The Clash’s attempts to start the ball rolling still smack of over-earnestness and desperation. That they acted as an inspiration for The Libertines is a blot on their copybook that can never be erased. Their lapses in taste and judgement could be spectacular, too. Though ‘Guns Of Brixton’ and ‘Bankrobber’ are among the most convincing slices of reggae ever cut by a white rock band, their lyrical concerns are toe-curling in the extreme, not least in the context of the gun violence that devastates communities across the globe.

This lack of editorial self-control also lead to moments of gross self-indulgence that are still best personified by 1980’s triple album, Sandinista! Ensconced in New York, The Clash, in common with many musicians who gain a new mastery of their instruments, took their newly found musical confidence and applied it to a host of musical styles which this time took in jazz, gospel, rap, dub reggae, children’s choruses, backwards tracks and instrumentals. A confused and unfocussed mess to this very day, it does much to mask the classic tracks contained here – ‘The Magnificent Seven’, ‘Police On My Back’, ‘Charlie Don’t Surf’ – and prevent anybody from delving into it to find the ten or 12 tracks that would’ve made for a tight and lean album whilst managing to lose any of the crucial messages contained within it.

The contradictions that lay at the heart of The Clash also caused them no end of problems. For example, their continued refusal to appear on <i<Top Of The Pops because they didn’t want to mime eventually blew up in their faces when the show’s dance troupe, Legs and Co, did a kitsch dance sequence to ‘Bank Robber’, thus reducing any impact they may have had to little more than unintentionally comedic light entertainment. It was also a strange position to take given that they’d take the decision to sign to CBS rather an independent label in an effort to get their message out to the widest possible audience. Their fascination with violent imagery and macho posturing was sharply at odds with the pacifisms they were endorsing while their jaunts into hotspots such as Belfast and Jamaica would come back to the haunt them as they realised the seriousness of the situations they found themselves in. Small wonder that Strummer would later sing on ‘Safe European Home’, “Sitting here in my safe European home / I don’t wanna go back there again”. Their love of rock & roll would also be held up as a fault both from the punks who’d come to destroy the form and the post-punks that followed in their wake.

But it was precisely these faults and contradictions that still make The Clash such an endearing and potent force; they serve to heighten and intensify their humanity, not diminish it. The problem facing any band dealing with politics and social commentary is that they are frequently held up to be a paragon of virtue or blemish-free. Yet who is? If anything, The Clash held up the difficulties inherent in the struggle for a better world. Indeed, it’s these perceived weaknesses that count among their many strengths. They may not have had the answers but at the very least The Clash were asking the right questions and in so doing sparked any number of debates, conversations and changes in the way the world was and is viewed. Of course, it was these frailties that led to their ultimate demise: Topper Headon’s sacking because of his heroin addiction; Mick Jones’ dismissal because of perceived “rock star behaviour” and Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon’s surrender of power to their management.

Yet for all their faults, The Clash left behind a powerful legacy that lingers to this very day. Possessed of a self-belief and potent creativity that saw them seek out new methods of expression and communication based on compassion and justice, the evidence contained within Sound System still stands up to scrutiny: the white heat of The Clash, the flawed fight back of Give ‘Em Enough Rope, the genre-busting London Calling, the glorious failure that is Sandinista! through to the stunning return to form of Combat Rock. This is a body of work that brims with ambition and a desire to make a difference. Though they all but vanished by the mid-80s, their shadow loomed large on that most divisive and politicised of decades.

Going back to that late night interview, Strummer summed up perfectly what The Clash was all about: "I’d say it was about making music that somehow had an extra dimension of meaning which I can remember from when I was at school; rock music had an extra dimension of meaning. We raised some issues that needed debating and probably altered a lot of people’s thinking about a few subjects. But I’m not here as a perfect example of anything. I’m just a lousy guitar player with a good right leg."

The Clash gave a shit.

Their music still gives a shit.

And so should you.