It’s always a fascinating conversation with Martin Newell, and this one promises to be no different. My opening ‘How are you?’ is met with an answer of ‘Well, I died…’, going on to explain how is was the huge creative side of his brain that brought him back so quickly. A brain that never seems to stop working, being perhaps both cause and cure of his brief departure to the other side. Already he’s recording songs for the follow-up to last year’s The Late District, tentatively titled Rubber Maid, and compiling the next set of Cleaners From Venus reissues, which promises to be even better than the second box set released this May. A new collection of poetry is out later this month, The Wife of ‘55, and on his blog Martin continues to write diary entries and sketches that may very well spiral into future books. There’s also a Cleaners From Venus film in the works, Devon Williams having filmed this songwriting genius for a few days in his native Wivenhoe. Newell is a man who has always believed that ‘great pop is to be had by doing things quickly’ and although he allows himself the luxury of fixing some things up these days, there’s still plenty of great pop coming.

How are you, Martin?

Martin Newell: Well, you know, I’ve been ill! I died briefly. So at least I’m up there with John Cooper Clarke and other people like that. I can look him in the eye now. With me it was just typical. Work-induced. An electrical short circuit in my brain. I mean it killed me very briefly. The neurologist said I bounced back from it only because I have this extraordinarily fit brain. He could tell from the scan that whatever part of my brain I use for creativity, I use a hell of a lot. He was amazed at how quick my memory came back. I lost a little bit of short-term memory for a couple of hours the first day (laughs). That’s all. He said some people don’t even start talking until two weeks later.

I’m a bit tired sometimes now. I went for a bike ride the other day, I did about 12 miles and found myself a bit tired. But everyone says I look very well considering what I’ve undergone (laughs). I haven’t been doing any gigs but I’ve been recording. I’m doing new tracks and writing my two articles. And I’m gonna start a book soon because while I was ill this strange thing happened. When I came back from it, and this is not uncommon, my awareness of everything seemed heightened – colours and sounds and everything. And so I thought we mustn’t waste this (laughs). Oddly enough, I kept going back to my childhood in the 60s. I’m gonna write bits and pieces about it, probably on the blog, putting bits down here and there. It might get a new book written.

And you’ve got a new record lined up?

MN: It’ll be the follow up to The Late District but it’ll be just a rolling program of work until I get something that looks like it’s an album. I would also be more interested in writing songs. I’ve got this side of me that likes writing torch songs and grown-up songs like I did for Richard Shelton. I like grown-up singers to cover my songs so I’m gonna write some. I’ve already written one called ‘Shimmering Eastern Beaches’. I don’t know what to do with it. But it’s a good, strong song.

I keep hearing some singer saying ‘I’ve done this cover of the Great American Songbook’ and ever since Rod Stewart did it some years ago, they’re all doing that now. They’re all doing the Great American Songwriters and this is fine, they are great songs – Sammy Cahn, Jay Lerner and all those guys. They’re people I learnt from. But there’s a saying ‘Follow not in the footsteps of the ancients but seek what they sought’ and as long as people keep doing these old songs, no one’s gonna write any new ones. I don’t think there are very many people who can write them anymore. But because I grew up at the feet of these masters, I don’t wanna sing the songs, I wanna write them. And I’m conceited enough to think I can do it. I’m of the age where I would do and I’m literate enough to do it. The thing about those Great American Songwriters, and one or two English ones, was they’d all read poetry, they’d read English. They weren’t dumbasses who wanted to sing about girls, cars, and chocolate all their life. They wanted to get to grips with the immensities of the failure of mature relationships (laughs). When you’ve got past say 35 and you’re thinking ‘well I’ve grown up now, why are things still going wrong for my love life?’ And this is something that everyone’s interested in. But the only people who’ve really written about it well are those great old masters.

How are you feeling about The Late District now that you’ve had a year away from it?

MN: I haven’t really brought it out properly. I would like The Late District to get wider distribution but then again all those Cleaners things were pretty obscure, weren’t they? (laughs). And I’ve just put together the bare bones of Volume 3 for The Cleaners. Not only that, I’ve remastered The Stray Trolleys. Now I don’t know what the plan is there but you’ve now got a director’s cut of The Stray Trolleys.

That’s great news. I love those Stray Trolleys songs and it took me a while to find them years ago. But there isn’t much information about The Stray Trolleys on the internet. Can you tell me some history?

MN: What happened was I was in this band called Gypp. And I’d been with them for three years and Gypp were a fine bunch of guys but they were fairly well-rooted in what we would call mainstream rock. We existed at the same time as punk. And in a parallel universe I would’ve gone straight from a glam rock band, which I had been in, and joined a punk rock band. And that very nearly happened cause I was in touch with those people in The London SS. But it didn’t. I did this Alfred E. Neuman thing and joined a heavy prog-rock band. We went to Germany and I did the rest of my apprenticeship. We did loads of gigs, about 150, 200 gigs in 1978 alone. But by 1979, I just thought we could go on doing this forever and I was very frustrated. I wanted to record and write three minute songs. That wasn’t gonna happen. So with a great deal of sadness and reluctance, I left and within three months I started recording these little 4-track songs. And I got a record deal almost instantly. With four songs. And that was The Stray Trolleys. It was basically The Stray Trolleys who did ‘Young Jobless’ and ‘Sylvie In Toytown’. I thought we were gonna go in the studio and make an album but I couldn’t wait. Record companies will hold you up forever. So I just told the record company I was signed to ‘look, I can make some demos’. I had some spare money so bit by bit we made The Stray Trolleys album in an 8-track studio in rural Suffolk. It was a learning curve.

Then because I was arguing with the record company who had signed me, sometime in 1980 I released it as my first D.I.Y. cassette. I used a pseudonym in case the record company got mad, so I think I called us The Dead Students. It was a very messy and confused time. We had a perfectly good album, there were some good songs, and nobody knew it was out (laughs). It never got reviewed, looked at, and by the time I finished everything we were on to the next thing which was The Cleaners From Venus’ early days. So The Stray Trolleys was buried all those years, nearly forgotten. We drank a lot, that band. I mean it was almost like a gentlemen’s drinking club formed around a bit of music sometimes. As soon as we finished recording we just hit the pub. You can see how it went wrong. (laughs)

Since you’ve been doing it from the beginning, what do you think about how releasing music yourself seems to be very popular and in some ways easier these days?

MN: This is quite difficult. The record companies used to control everything. I’d been at it for a while and in the end I just thought ‘look, I can’t live with this so isn’t it better if I just sell 200 copies of everything and remain free?’ I could always go and wash dishes or do people’s gardens but it’s gonna destroy my love of music if I deal with the record companies. So I made a conscious decision not to associate with anyone in the music business and that worked very well as we can hear from The Cleaners From Venus. The sound quality wasn’t good but I always did what I wanted (laughs). Nobody told me what to do. And that was great.

But now, everyone, even amateurs, are making these great art statements. They set up a Facebook page and get themselves on Soundcloud and everyone’s got a little thing going. Uh…well that’s alright. But this is saying that art and music is for all. That was the stance during the last political administration here. And I came to the conclusion that art isn’t for all. Any more than eye surgery or astrophysics is for all (laughs, for a while). It’s very easy to go and do some music. Mick Jagger said ‘a lot of people do pop music because it’s easy to do’. But what I’m listening to or rather what I’m not listening to is songs. There are loads and loads of people writing songs. There’s a school of thought about how songs should be written. But people aren’t writing good songs. I can’t remember when songs were so mediocre, so boring. And so dreadful and so self-indulgent…the lyrics are so shit. (heavy sigh) You know, I write good songs now, but it’s taken me decades, and I’m a wily old dog. I’m still learning from great old masters who were before me. I see myself as having a lot to learn. And I know a lot more than the people who consider they have nothing to learn. So I don’t know what to think really about all these people.

There’s this bloke in my village who said ‘The problem is today that the audience is up on the stage’. You’re looking at things like Britain’s Got Talent, America’s Got Talent, Shame Academy, Smashed Dick Knee Showcase, I don’t know what you call it. And what you’ve got is people who work in call centres who can do not-particularly-elegant forgeries of songs that were mediocre and shouldn’t have been hits in the first place. And that’s horrible. The really good thing about it is it keeps them out of my hair. The one thing I can say when I watch those shows, which I don’t cause I got rid of my television, but if I do ever catch some I can honestly say at the end of the program, I don’t know why artists are getting annoyed about this because I think it’s great. It keeps everyone off my fucking back. When somebody says ‘What do you think of the awards ceremonies?’ and everyone’s saying ‘I think there’s too much business creeping into the awards ceremonies’, I think there’s too much music creeping into the business ceremonies (laughs). They should just have somebody say ‘Look, look how much money we made here’ then give themselves their little gongs and their awards and all the businessmen can shake hands and why have any music there at all, you know? (laughs)

Looking at your work as a whole, I’ve noticed that all the seasons come up in your titles. Summer particularly, and autumn as well. Why do you think that is? Anything to do with being a gardener?

MN: Working as a gardener yes, but I’ve been acutely aware of them. I became more aware of them when I came back from the Far East. I was living in the Far East for about two and a half years on and off [his father was stationed there when he was young] and when I first came back to England I really noticed them. You don’t really get seasons in Malaya or Singapore, you just get a rainy season. And I longed to be in England then. The 60s was going on and I was in Singapore in the tropics. Although it was still the 60s. I’m going to write this book about it, because it needs to be exorcised. But the seasons come out of that because England has these very distinctive seasons. You really notice them.

Looking at the titles too – the colour ‘gold’ comes up a lot on this second batch of records – ‘Golden Autumn’, ‘Golden Age Saturday’, ‘Golden Lane’.

MN: (with joy) It does, doesn’t it? I’ve noticed that too. I don’t know why but green and gold seem to be the two colours that I associate with England. The two of them in some kind of conjunction. Which you’ll get in spring and in autumn. England in the very early summer can be several shades of green and it’s a very deep green. When the sun filters through that canopy of leaves, especially early in the morning or late in the afternoon, you have this kind of wonderland. Can be quite extreme, really.

I wanted to talk to you about ‘Drowning Butterflies’. I said in my review that it’s the ‘Marilyn On A Train’ of this box set, a really perfect pop song that is now available in multiple versions. What inspired you to write it?

MN: I had that great riff, the guitar pattern which is done on an open D. The Miners’ Strike was going on and I do remember one of the guys saying ‘I was gonna get married when I get back, but we haven’t got enough money and I don’t know what’s gonna happen in this strike’. He seemed to be in some doubt as to whether it was worth him and his fiancé staying together. I made it a bit more dramatic, with the guy saying to his girlfriend ‘look, I’ve only got four figures redundancy pay, that’s not gonna get us through married life and kids, you know’. It was serious, serious enough in its way, his whole life fell apart after that. So all that was fermenting around in my head, I suppose.

The Miners’ Strike had a huge influence on Under Wartime Conditions.

MN: It did! There were good things as well. It was a nice summer, once it calmed down. It started off really well, the strike didn’t really hit Wivenhoe until about mid-April and I had already done ‘Johnny The Moondog’ and I think ‘Summer In A Small Town’ by that time. But I was writing about England anyway because by that time the 80s was definitely making itself felt – Reaganomics, Mrs. Thatcher, we’d had a war… She’d only been in for about four and a half years and we’d already been at war…lost this, lost that, smashed that up. It was looking bad. At the same time, the people who liked it were strutting around, wearing their new money. And saying how great it was. It wasn’t a good time to be poor in the south of England, put it that way.

Around Under Wartime Conditions you started writing for the national papers too?

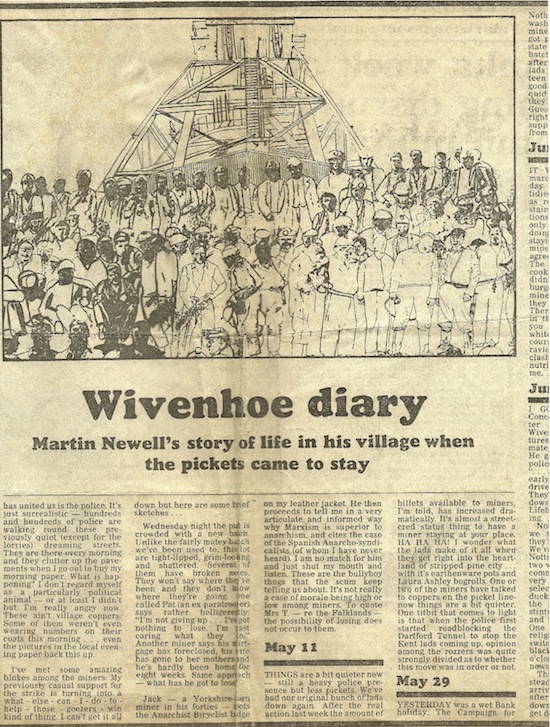

MN: I had one article, for The Guardian, which was a big deal. I was just keeping a diary. Polly Toynbee had written an article about the Miners’ Strike in The Guardian which I didn’t usually buy but I read it and thought ‘this woman’s obviously never met a miner!’ She was writing about them almost as if they were…that image that D.H. Lawrence had of his Dad, or George Orwell. I thought ‘This is typical’. So for the first time ever, I wrote a letter to The Guardian. Saying ‘Polly Toynbee has got this well wrong. I’ve got miners staying in my village and I see them all the time and I put them up. They’re good guys and we should be fighting for them but with all the best will in the world, they don’t look like this and they aren’t like that. They’re just guys who want to get back to work. They’re not some sort of political tool.’ Most of the miners said to me ‘look, I don’t want to be doing this, I’d just rather be back at work in my old job’. They didn’t want to be on strike, who does? And I mentioned I kept a diary and suddenly the editor of the Women’s Page writes back to me and says ‘we’d be really interested in seeing your diary’.

I thought they were pissing me about but one evening I came home and typed up something like seven pages of my diary to do with the Miners’ Strike and sent it off. And then much to my absolute astonishment, three weeks later, I filled a page. Great big article. I still behaved pretty much like a straight-from-central-casting-rock-n’-roller in those days – fag in mouth, bottle in hand, talking only about music and not interested in anything about the rest of the world. And suddenly, in a scene redolent of something from The Railway Children, I was cycling to my washing-up job one morning and a 2CV passed me on my bicycle on a country road and they were waving their Guardians out of the window at me in a very excited fashion. And I thought ‘well I don’t fucking understand what this is about’. It wasn’t until I got into the restaurant to do my washing-up shift at about half past nine that someone said ‘oh, someone’s phoned up for you, apparently you’re in The Guardian’. And they said ‘I bought a copy, do you want to see it?’ This was apparently a really big deal. It was great! But it wasn’t a big deal for me. It would’ve been better if someone had said ‘hey! your record’s been on the radio’, that would’ve meant something. But whether I liked it or not, this would be the slow fuse that kickstarted my writing job. Because I’d done that. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that I realized they were going to pay me as well. People were asking ‘what are you going to do next?’ I said ‘I’m gonna get on with my album as soon as the miners have gone home’ (laughs).

What was it like re-visiting the three records that just got re-released and putting this boxset together?

MN: I put it together some months ago actually. I’m just starting to listen to bits and pieces of it now. I think the third set’s going to be even better again. Because that will comprise Living With Victoria Grey, Number 13, and my director’s cut again of My Back Wages. It’s amazing, in it I found a lot of the demos that became The Greatest Living Englishman. A really really good version of ‘She Rings The Changes’. Which I’m not sure I don’t prefer to Andy (Partridge)’s version. My version of it is quite powerful, more powerful than Andy’s. It really thunders out (plays it for me over the phone, he’s right). It just comes in like a ton of bricks. So that’s coming up next.

Last time we spoke, I asked you what you’d want to listen to if you were flying directly into the sun, and you said maybe ‘Julie Profumo’. What’s so special to you about that song?

MN: I just like it. The one on Going To England, it kicks in and says ‘this means business’. Also it is like a cry from the streets. I’d written that one really after Thatcher and 1980s monetarism had nearly ruined the land I grew up in. And I’m saying ‘well I’m still here and I’m still saying this and you might’ve taken that but I can remember it and I’m gonna sing about it is what I’m gonna do’. All the music, the country, and everything had got shot to shit but I still felt I’m gonna fly the flag here. So I wrote it as if it were the last song I’d ever write.

Martin Newell will be performing his yearly gig, The Golden Afternoon, at Colchester Arts Centre Sunday, September 22nd