In 1963, Pierre Boulle, author of 50s’ bestseller The Bridge over the River Kwai wrote La Planète des Singes, an unanticipated success that would eventually give us the Planet of the Apes film franchise and several decades of disturbing prosthetics. But, by the time James Franco and Mark Wahlberg got involved, the original story had mutated into action-heavy, plot-light popcorn fare (the latest being 2011’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes) – a shame, because the book is great and its offspring, as most parents know to be true but refuse to say out loud, far from does it justice.

The premise is both smart and simple: in 2500, a bunch (a shrewdness?) of French scientists travel to a distant star and land on an Earth-like planet. When they look around, they soon discover that’s where the similarities end – that this a planet on which monkeys are king and humans mere primates. This inversion sets the stage for a neat philosophical allegory; a series of tongue-in-cheek revelations about the way things are and the way they could be, and about human carelessness and complacency.

Imagine falling in love with a woman so beautiful at first glance that you’re convinced she must be the apex of creation, and then finding out that instead of communicating with language, she can only mewl, grunt and growl. In Planet of the Apes you know it’s coming, but when the hero, Ulysse, realises that his dream woman – and all the humans on the planet he’s landed on – aren’t capable of communicating beyond primal utterances, it’s an excellent moment of dashed desires and comic bathos.

When he’s then captured by apes and sees that he’s going to be treated like his fellow humans – that is, like an animal – Ulysse urgently needs to prove he’s as intelligent and civilized as his captors. On one level, here you’ve got a classic sci-fi set-up: the space opera voyage to a distant planet and the inevitable antagonistic encounter with the alien. But what’s beautiful – and no doubt the reason for its enduring popularity – is that in this case, what’s alien is life on earth flipped around –man as monkey, monkey as man. So it’s not just tangentially alien, it’s the diametric other. And then there’s the corresponding headfuck: it’s apes in suits, munching on sandwiches, strolling through the park. It’s the other as ourselves.

Confronting this uncanny beast – the inevitable psychological drama that occurs when lines between self and other are blurred – means accepting to some degree (depending on the level of antagonism) a connection between the two. And Ulysse is desperate for connection. Luckily, a sympathetic chimpanzee scientist called Zira sticks her neck out and believes he is who he says he is. They become friends and she helps him win over ape society. He soon becomes accepted as an anomalous intergalactic visitor, rather than a freakishly intelligent human. But it turns out you can’t be a civilized, eloquent dude from Earth on a planet where all the other men do nothing but howl and grunt without causing a bit of a ruckus.

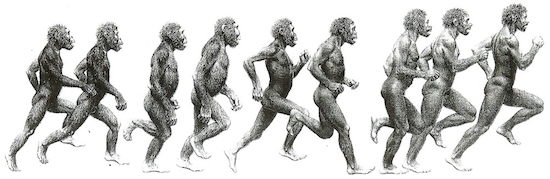

Here’s where the novel’s evolutionary ballast comes in. The monkeys are paranoid about humans because their own civilization seems to have just appeared out of nowhere, and they’re worried as to how this could be. They also know that their own scientific, technological and cultural progress is worryingly sclerotic. The vanguard of monkey scientists have a needling fear that humans were there first, and that ape civilization rose later, based on transfer of knowledge through imitation. This runs counter to the evolutionary theory perpetuated by their scientists, which is that humans are just an embarrassing mutant offshoot on the tree of life, good for nothing but subjugation. Zira’s fiancé, Cornelius, isn’t scared of the former being the truth: “Ego is nothing compared to science,” he says, but others are far less willing to find out where their civilization truly stands in the great chain of being. It’s a sharp take on one of the oldest science fiction tropes. Usually, the fall of humans is accompanied by the rise of machines. Here, we’re going backwards for once – such a rare thing in SF – but it’s an equal fiction, as civilized apes are just as entertainingly unlikely as conscious machines.

In any case, Ulysse finds out that their civilization has indeed risen from our ashes – our complacency and laziness have allowed us to be usurped by monkeys. It turns out that humanity is excessively easy to ape after all. It’s a strong case for anti-anthropocentrism, and there aren’t enough such fictions around. It’s so much fun to be tantalized by eerie visions of where our self-destruction might lead.

The novel also works on another level as an animal rights polemic. There’s a powerful section where Ulysse is made to witness some of the encephalic experiments that monkeys are performing on humans. When human brains are being mutilated for science, in Boulle’s capable hands it’s some nasty shit. Perhaps it’s a pretty obvious transposition – particularly to us in the here and now with the "benefit" of Rupert Wyatt’s oh-so-subtle prequel – but when you’re swept up in the tide of the novel, it just works.

Maybe most strongly, it’s a novel about freedom. Boulle himself knew a fair bit about captivity. He was a secret agent for the Resistance during WWII, captured by Vichy French loyalists on the Mekong and subject to two years’ forced labour (the backstory for The Bridge over the River Kwai). And so the recurring image of Planet of the Apes isn’t of its dictatorial eponyms, but that of humans in captivity, utterly at the mercy of their oppressors. Even on a distant planet, even in alien conditions, this most dismal of power relations persists. Boulle seems to be suggesting that the need to colonise and control the other, rather than communicate and co-operate, is inevitable.

Planet of the Apes might not be high art, but it definitely put a few things in perspective. Are humans destined to self-destruct? Why do we think it’s all about us? Are some dynamics inescapable, whatever galaxy we’re in? For a surprisingly jaunty trawl around these questions, skip the movies – all seven of them and the forthcoming eighth – and head straight for Boulle.