Here is a picture of two men sitting at a kitchen table in Glasgow. One of them is Mogwai’s Stuart Braithwaite; the other is artist Douglas Gordon.

That is a bottle of ginger wine, of dubious alcoholic volume.

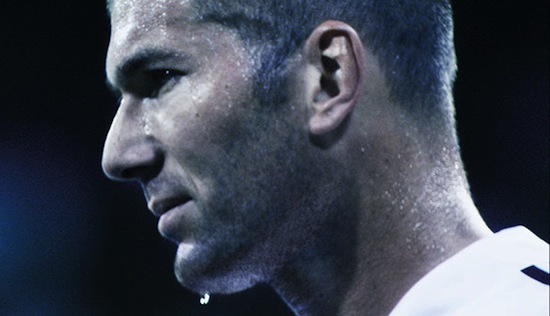

This is the product of a 90-minute conversation in Gordon’s Scottish residence (he lives and works in Berlin). An hour-and-a-half: the length of a film, a rock concert, a football match; the duration of Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), which is all three and yet none of these things. Directed by Turner Prize-winner Gordon and French-Algerian collaborator Philippe Parreno, Zidane is a real-time cinematic feat of portraiture that follows footballer Zinédine Zidane on the field during a Real Madrid vs. Villarreal CF game on April 23, 2005. From the first kick to the final whistle, it charts the subject, not the ball; focuses on the hero, not the narrative. It is a still and hypnotic depiction of a man at work.

Zidane was exquisitely soundtracked by Mogwai, who’ll perform it live with the film for the first time at Manchester International Festival (July 19th and 20th), followed by performances in Glasgow (July 21st) and London (July 26th).

We will speak about Zidane at length, amid deviations into Thatcherism, spiritualism, Mississippi Records, The Corries and the brown note. Braithwaite will serenade us with nylon-strung axe-mastery and croon Ivor Cutler’s ‘If Your Breasts’ accompanied by Russian improv harmonium; Gordon will scar a woman’s retinas (loins) for life (in a good way) when he reveals he wears braces against his bare skin while demonstrating how The Gaslamp Killer’s "massive fucking frequencies" made him throw up into his t-shirt.

It’s a story about a man doing his job.

You join us as Gordon muses on screening Zidane with Mogwai live in Manchester…

Douglas Gordon: It’s the first time that the band have played with the film, but this is an idea that we’d had for a long, long time, and I’m delighted that it’s happening. I love Manchester, and it’s a very special venue – it’s a Wesleyan church-slash-chapel, and it’s about choir, you know? It’s this idea that your audience are a choir, which is a football match. It goes back to something that John [Cummings, Mogwai] said when we originally met to talk about the project, which was that the frequency of the stadium is something special.

Stuart Braithwaite: I think that environment is one of the most important things about how you perform, and how you absorb, art. It’s a character in the story. I think that every time that you play something, or every time that you hear something, or every time that something of yours is performed – where you are, and where it’s performed, is almost as important.

DG: The way I’m looking at it, Manchester is a testing territory for future stuff. It has to change. As artists, just making a replica of something is not enough.

SB: We’re going to do the opposite of Thatcher – test it out on the English, see how that works.

[Laughter]

DG: My hilarious, gigantic ego idea was that we should have premiered the film during the [2006] Cannes film festival, but in Marseille, in the [Stade] Velodrome. I really fucking pushed this, but the studios were more concerned with reviews and stuff. I said, ‘You just don’t fucking get it, do you? If we do this in Marseille, where he’s from, we would have gotten global attention.’ But I just had to sit back. And of course, Zidane couldn’t come to Cannes because he was training for the World Cup, but he would have come to Marseille, without a doubt. I still think it’d be so massive, maybe on the anniversary of him turning 50 or whatever, a bunch of wee Scots folk, praising in a way – no, stop that – recognising the significance of a fellow like that, in his home town. I still want this. Look, I’ve had a lovely and charmed life, but if people say to me, ‘Is there something that you want to realise?’ I say, ‘Aye. I want the Zidane film, with my friend Philippe, and my pals from Mogwai, in Marseille’.

Douglas, at what point in the film’s conception did the idea of a Mogwai soundtrack arise?

DG: The funny thing was that I knew Stuart before – if you went to Art School in Glasgow you know people – and I remember one night, I think it was at Optimo, and I bumped into Stuart and John and Aidan [Moffat], and we got into some bizarre argument about football because, you know, they’re kind of – [whispers] – Celtic. I’m a Partick Thistle fan. So we knew each other, we all had some nice evenings here with guitar and singing and stuff. Anyway, eventually, when we were halfway through editing the film, Philippe said, ‘Listen, we have to think about soundtrack.’ But I’m kind of Calvinist. I was like, ‘I don’t want a soundtrack on this.’ But as it happened, I was in Paris editing with Philippe, and Philippe goes to Manchester to speak to [MIF Artistic Director] Alex Poots, and then Philippe comes back and says, ‘Listen, we really need to address this issue of sound and music’, and he hands over this list of ideas. It was like, Boards of Canada, Four Tet – ach, I don’t know, The Corries or something… [The Corries were a ubiquitous Scottish trad-folk duo in the 1960s and 1970s. One of them, Roy Williamson, wrote ‘Flower of Scotland’.]

SB: Were The Corries really on the list or are you just being facetious?

DG: Always facetious.

SB: I’m just thinking – that would have been brilliant. Have you heard that record The Corries made, where they made all their own instruments? You would fucking love it. It’s called Strings & Things. Have you heard it, Nicola?

My granddad had the tape in his car when I was wee, it’s amazing. My first-ever gig was The Corries at Stirling Albert Hall when I was four or five.

SB: Oh that’s brilliant, I love that.

DG: What the fuck is this, The Corries faction?

SB: Honestly Douglas, that Corries record will blow your mind.

DG: Do you know that my tutor, David Harding, was the third Corrie? In the 1960s. Anyway, aye – the sound-track – Philippe came back with this list of names, and there on the list, of course, was Mogwai. This was kind of incredible that Philippe would go to Manchester and come back with the name of a band who were friends. And I knew that most of them were into football, and that they’re incredibly intelligent about sound, and they know what the stadium is about. So that’s when we kind of kicked it off. Philippe and I came over to Glasgow, and met up with Mogwai. It was a beautiful conspiracy of sorts.

How did you convey the idea of the film and soundtrack to Mogwai?

DG: We made this wee mix of music with – what’s the first track on Mr Beast, ‘Glasgow Mega Snake’? ‘Auto Rock’?

SB: No it wasn’t, it was one off Happy Songs [For Happy People], it was – what’s it called? I can’t remember the name of it. What is happening with that wine? It was – I remember the song, I just can’t remember the name…

[Braithwaite paces round the kitchen table, picks up an acoustic guitar and starts playing it.]

SB: It was this one – the one that’s exactly like The Cure…

[He plays ‘Kids Will Be Skeletons’.]

SB: When Douglas and Philippe came and showed us the footage, it was of the last 15 minutes, and it had that piece of music, and it was just so intense and so weird – the whole thing was very psychedelic but also very honest, and it just really appealed to us. When we started writing, there was a certain tone suggested by the film, and I think we really just did it in quite an instinctive way. We’ve always had this attitude when we’ve done soundtrack things where we did not want to be – well, we’re soundtracking something. We’re not attention-seeking.

DG: One of the best things I ever saw was in a place called Webster Hall [New York] and I think it’s a band called Mogwai – from what I remember, you guys in yellow tracksuits –

SB: – green –

DG: – with your backs to the stage, which of course is a wonderful quotation on everything. I’ve always loved that. Every time I’ve come to see what you do, I don’t have to look. No need.

SB: Alan McGee [who managed Mogwai] always said that was one of the best things we had going for us was that no-one actually cared what we looked like, so we could keep going for years. Like Kraftwerk. Thanks Alan. That was a compliment of sorts.

Was there a suggestion, then, that you were inter-changeable?

SB: There was, aye.

Perhaps it’s time to bring a woman into the Mogwai ranks?

SB: Aye, we’ve done the five ugly guys thing to death.

I think the first time I saw Mogwai was Upstairs at the Garage in London in 1996 – there was no need to watch you until the point that you started climbing the speaker stacks and hanging from the ceiling. But it seemed like an extension of the music, than rather than posturing or choreography.

SB: I think that was simple attention seeking to be honest – it had obviously dawned on me that nobody was looking at me.

DG: I always thought that Mogwai would be perfect if they were choreographed, actually.

SB: It’s too early in the night for these terrible ideas.

[The room descends into laughter then spirals into momentary confusion as Gordon forgets the name of a member of Mogwai. Even when Braithwaite tells him the name, Gordon still can’t remember it.]

SB: What’s going on here? It’s like some kind of Timothy Leary situation is happening with the wine. Who gave you this wine, Douglas?

[It is home-made orange-coloured "wine" in a square bottle with hand-written insignia, which may or may not read: DRINK ME.]

DG: I feel totally flushed. I feel like I’m completely flushed.

SB: One of the things that I really liked about Zidane was that it was bringing people in that wouldn’t normally be in art-house cinemas; it was letting people hear our music that wouldn’t normally experience it; it was letting people see a work of visual art that maybe wouldn’t normally experience it. That was something that annoyed me somewhat when Zidane was released. A few people – not many, because generally it was received really well – described it as pretentious. And I remember thinking, ‘Okay, it’s not for everyone, I can see that, some people would not have the patience to watch this, might have no interest in football, might not know who Zidane is, or might not like our music – fair enough – but it’s actually one of the least pretentious films of all time’. It’s incredibly unpretentious. It’s just a portrait of a guy at his work. There isn’t even a concept.

DG: This is a work that needed to be done. It’s completely unpretentious. And it’s not about a footballer. It’s about a man. That’s really important for me. It’s a portrait of a man who works, and since I am a man who works, there’s a line – let’s call it a wavy line. When Philippe and I met Zidane, we immediately said, ‘We don’t want your autograph, we don’t want to be photographed with you, we just want to do this thing, and we want it to be in a museum so that your great-great-great-great grandchildren can see an image of their great-great-great-great grandfather’, and he kind of got that. And I think that was really important – not just for him, but for me, because I think when you get to my age, there is an issue with legacy. And it’s an interesting thing for me, working with people like Stuart or Barry [Burns, Mogwai], because the legacy of music has an importance that’s way different to anything else – there’s the distribution of it, the fact that kids can mimic it … Writers, that’s of course language-based, it’s a lot to do with typography, calligraphy; and making paintings or the shit that I do, it’s not the same. Growing up with a father who was a bagpiper, I’m always jealous of people like Stuart – really, seriously – that’s an issue.

SB: I heard the most amazing thing yesterday, I collect the Mississippi Records label, and they put out this record by a Russian spiritualist called Gurdjieff [a key influence on Timothy Leary]. He made these harmonium improvisations, and he was almost like a cult leader by the time he died in 1949, and it’s one of the most amazing things I’ve ever heard. So yeah, I kind of know what you mean about music, Douglas, because there is a permanence there, and there’s an unspoken thing, and because we live in such an explained time: everyone can understand almost everything now, but with music, and art, and film, one person can experience something and find it incredibly moving, and yet it doesn’t affect another person. How does that work? It’s almost like the little magic that’s left in the world. I’m going to see if I can find Gurdjieff on YouTube and play it on my phone right now – it’s that good I think it would carry.

[Braithwaite starts searching for Gurdjieff on YouTube…]

DG: Arvo Part. I had this meeting with Alex Poots because I’m trying to write a musical – I’m clearly so camp that I need to write a musical – and I said to Alex, ‘Let’s get Arvo Part to give us three notes.’ Because that’s a challenge – what would that be? How would it be sequenced? All we need is three notes. Ach, you know, I’m very happy with my life and all that kind of thing, but I hope that at least one of my kids is as interested in music as I am.

[Gurdjieff starts emanating from Braithwaite’s end of the table.]

SB: Found it! I’ll play it in the background.

DG: This sounds like Ivor Cutler.

SB: Well, it is a harmonium. Same instrument.

It’s lacking Ivor’s dulcet tones.

SB: [Quoting and mimicking Cutler] "If your breasts are too big / you will fall over…"

[Laughter]

Stuart, I know Mogwai have done other soundtracks – most recently Les Revenants– but was there a particular dynamic, or symbiosis, with Douglas and Zidane?

SB: Yeah, this was different. I think a big part of it was the freedom that Douglas and Philippe gave us, and I think that that probably – no, definitely – comes from them being artists, and probably despising people telling them what to do. And that’s why you make music; it’s why you make art – because you don’t want people to tell you what to do. I’d fucking hate it if someone told me what to do. And people do occasionally tell you what to do. And it really pisses you off.

DG: I spend a fortune on therapy. Really. And I’ve realised through therapy that I’m a hateful, independent cunt.

[Laughter]

That sounds like it was worthwhile. Was it worth the money?

DG: "I never realised this until a few years ago, but I’m desperately against anyone telling me anything actually. Not even what to do, just anything —

SB: What the specials are on the menu…

DG: I’m not ever fucking accepting anyone telling me what to do. And this is why we did Zidane.

[They drain the bottle of ginger wine.]

SB: This is the longest interview I’ve ever done in my life.

DG: Did I ever tell you about the time I lived in a squat beside The Shamen?

And so we leave these men at work, zoom out on them at the kitchen table. Come back down the stairs and out into the rush hour. Pull the door behind you.

Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait with Mogwai live takes place at the Royal Albert Hall, Manchester (July 19/20); Glasgow Broomielaw (July 21); London Barbican (July 26)