Watching a rehearsal of his new play in Annie Hall – two characters having a conversation very similar to a scene we’ve watched earlier in the film, but this time with Woody Allen coming off as suave and self-possessed rather than bumbling – the notoriously self-referential director turns to camera, shrugs, and says: "What do you expect? It was my first play." At least Allen, whose best films tend to centre on a comic cipher of himself, has the self-awareness to tip his audience a wink. If you ever want to convince yourself of the inutility of creative writing, imagine the many, many slush piles laden with books that tell an unexceptional personal story wrapped in a thin gauze of literary merit.

Making characters and stories up is hard, and writing about yourself is easy – just look at alt.lit – if it involved any less effort it would consist of ambient recordings taken when your iPhone turns on its microphone by mistake. Right? B.S. Johnson didn’t think so: In his second novel Albert Angelo, the English novelist barrels along with a modernist romp about an architect struggling to make ends meet, while pursuing his ambitious creative aims, for three sections. The fourth, entitled ‘Disintegration’, opens with a thunderclap: ‘Fuck all this lying what I’m really trying to write about is writing not all this stuff about architecture … telling stories is telling lies.’ Delivered with the trademark Johnsonian brio, this statement was to characterise his work, and loll over his short life like a thirsty tongue.

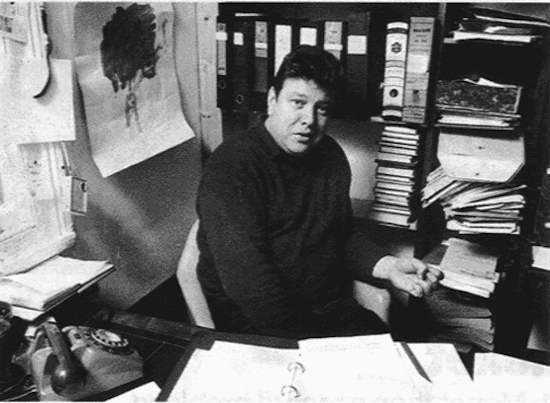

Born in 1933, the author published seven novels before his death forty years later, as well as working in journalism, writing poetry and producing avant-garde cinema – Fat Man on a Beach is a fine example of his highly personal style, which was generally focused on issues of mortality and sex. Although he achieved a degree of notoriety during his lifetime, not least for his publisher-mithering typographical experiments (Albert Angelo has several pages with holes cut through them, while The Unfortunates is a sheaf of loose pages contained in a box to be read in any order), he has never achieved the canonical status granted spiritual forebears like Joyce and Beckett.

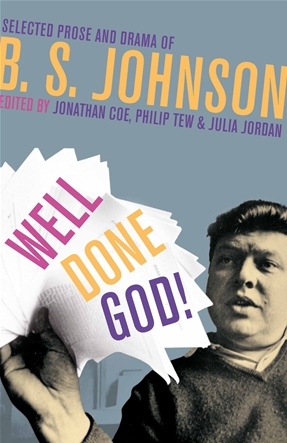

There are hopes that recent developments, such as Jonathan Coe’s well-received 2004 biography, will see him move into a more prominent position. 2013 is both the 80th anniversary of his birth and 40th of the end of his life, with several republications and events planned to mark the occasion. And, like the Velvet Underground’s first record, Johnson’s novels have always had an influence that belies his lack of popularity.

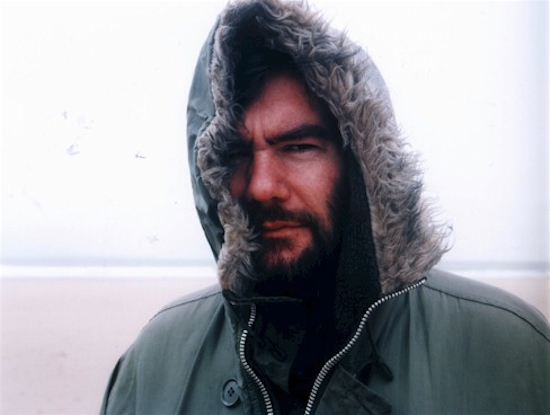

Aidan Moffat, formerly of Arab Strap, recently released a version of Johnson’s poem ‘The Poet Hold His Future In His Hand’ – typically for both, it concerns the penis. He choose that poem to record in the hope that it would turn new readers on to Johnson, after he recognised a ‘kindred spirit’ in his books: ‘Penises and mortality, and more recently ageing, are certainly thematic concerns we seem to share. He can also be hilarious, particularly in a self-deprecating way that I really relate to.’

Moffat also feels that Johnson’s attitude and innovative treatment of form mean he is ideally suited to the modern cultural climate, "He was arguably pioneering interactive books – something we take for granted now – in the late sixties. He wasn’t alone, of course, and nor was he the first, but his enthusiasm was unmatched."

His frankness about old age and sexual failings – another trait his writing shares with Moffat’s, especially in his latest collaboration with Bill Wells – remains a welcome panacea to a world where the elderly are typecast as punchlines or charity cases. He offers a clear-eyed look at the brakeless ride of the ageing process, undercut with humour to leaven the morbid side to his nature. "I think some people are maybe simply too afraid to discuss these things, there’s still a lot taboo around old age and the C Word," Moffat explains. (That’s cancer, not the other C Word you might associate with Arab Strap.)

Given the similarities in their writing, does Moffat ever feel the same anxiety that beset Johnson later in his career, when he realised that it could be difficult to write from life if he ran out of material? ‘I don’t let it worry me, I just make sure I write as best I can. If I’ve felt something, then other people have felt it too – the personal really is the universal, and the way you say it is what really matters.’ This admirably level-headed view, it would be fair to say, was not shared by Johnson. A mercurial character who could be extremely gracious and showed great loyalty to his friends, he was also an obdurate scourge of publishers who he felt did not appreciate the scope of his ambition.

Lukewarm reviews and poor sales left him embittered and choleric, as well as uncertain about how to escape the corner his obstinate approach to the creative process led him to. Coe, describing Johnson near the end of his life, said ‘he could not see where his radical aesthetic must inevitably take him … either towards Beckettian minimilasm or to a sort of insane Joycean inclusiveness’.

Modern writers have struggled with the same dilemma – alt.lit posterboy Tao Lin’s blank, affectless prose and David Foster Wallace’s frantic maximalism represent two different run-ups towards the same hurdle. However, as Coe suggests, Johnson is one of the few writers we have who have been willing to seriously scrutinise the form and treat it as though it mattered, an attitude that seems especially crucial in the modern world of writing as text proliferates across the internet like frost.

Another fan of Johnson’s, the mononymous “Gareth” from indie act Los Campesinos!, was recommended one of his books, Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, a few years ago and has made his way through the canon since then. The novel, one of Johnson’s more conventional efforts, tells the story of a disaffected clerk who applies the principle of double-entry book-keeping to his own life – crediting himself against society in an increasingly violent for the debts he feels it owes him. This kind of totting up of the past and its difficult consequences sounds like grist to the mill to LC!, with the lyrics inspiring either vitriol or admiration for their focus on old, generally troubled, relationships: ‘Since first reading Johnson, and, perhaps more importantly, reading about Johnson, he’s influenced me to write personally and honestly. I know it’s not to everyone’s tastes, and there are plenty of people whose main reason for disliking the band is my lyrics and their perceived bedwetter-y nature, but that’s the only way I’m really confident in writing.’

With all this in mind, one wonders if he might also fall prey to those same demons as Johnson – shrugged off by Moffat: ‘I can understand Johnson’s concerns, and perhaps share them a little. Right now I’m in a relationship that I’m very fond of, and LC!’s shtick for four records has basically been being in unhappy relationships. But there’s plenty more melancholies to toy with and write about.’

Gareth also cites his interest in football as a factor in his fondness for the writer – like Beckett, Johnson was a keen sportsman and later went on to cover games for the Times of India, among other publications. He even made a bid to make the feature programme for the 1966 World Cup, although his script was dismissed by the startled Football Association as too off-the-wall – not a situation we’re likely to find Gary Linker and company embroiled in. ‘Football fans’ reputation among non-football fans is often that we’re stupid, aggressive simpletons, so someone as supremely intelligent as Johnson being so passionate about the sport is one in the eye for the naysayers.’

He has been vocal about his enjoyment of Johnson’s work over the years, and along with Moffat has expressed his hope that the on-going anniversary year and new publications will make him more accessible to contemporary readers – we can only hope. As a man with one eye on posterity from early on in his career, it is gratifying to see that the novelist now has the opportunity to establish himself firmly as part of English literary heritage, especially given the manifold frustrations that prickled at him throughout his publishing life.

B.S. Johnson, struggling with the collapse of his marriage and drinking heavily, committed suicide on 13th November 1973. His final poem, written on a card and left on his desk, was suitably oblique:

word.

Well Done God!: The Selected Prose and Drama of B.S. Johnson is available now, published by Picador

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more