Damien Echols is hanging curtains with his wife Lorri in their new home. It’s a bizarre mental image and one that’s difficult to imagine considering just over a year ago he was in a 12-foot by 9-foot death row cell. But, as Echols states, doing such mundane every day household chores is helping him rehabilitate after spending 18 years in what the US prison system calls a ‘super-max’: the highest maximum security facility reserved for incarcerating the most dangerous criminals in US society. Over a year after being released, Echols is still coming to terms with the psychological adjustment.

"I had difficulty – I was in a state of deep and profound shock and trauma," he says of life immediately following his release. Not used to walking without his legs shackled, Echols would trip when using stairs – unaccustomed to the freedom of a longer gait. "I couldn’t function by myself on a daily basis. I’ve come out of it and become more independent but there’s still a lot of anxiety and stress; you don’t get over 18 years of torture and confinement in one year."

The Robin Hill Murders in Arkansas and the notorious case of The West Memphis Three is the highest profile death row cause célèbre in modern history, along with that of Mumia Abu-Jamal. It’s been documented on TV, film, book and internet. It’s been picked apart, dissected and examined in close detail time after time, so it’s not something we’re going to go into great detail here with Echols – who, at age 37, has now been protesting his innocence for half his life. "I hate talking about this case," says Echols, who speaks with urgency, as if he’s still running out of time, with that familiar deep-southern twang to his accent. "It’s the thing I hate most in the world. It’s never going to heal because I’m constantly ripping the wounds back open. I don’t even really try to defend myself any more. I just talk about my experience. This case is already 20 years of my life. I’m not going to give it 20 more."

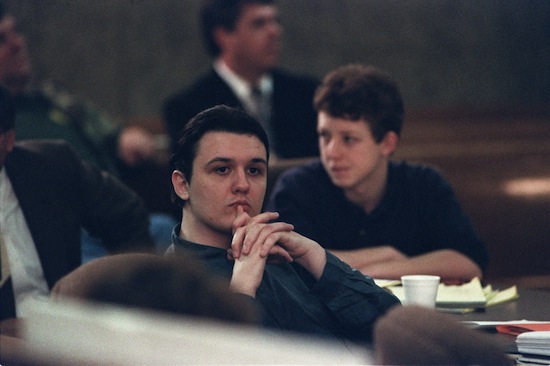

In 1993, three eight-year-old boys were murdered in West Memphis, Arkansas. Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, Jr were arrested, charged and – in the following year – found guilty of the murders. However, the entire case was riddled with fabricated testimonies, police coercion, mishandling of the crime scene, alleged corruption – not to mention political agendas. The prosecution attorney of Arkansas – a state situated in the deep south, the heartland of America’s bible belt – asserted that the boys were killed as part of a satanic ritual. Echols was deemed the ringleader of the three and sentenced to death. Misskelley was sentenced to life imprisonment plus two 20-year sentences, and Jason Baldwin was sentenced to life imprisonment.

A HBO TV documentary titled Paradise Lost: The Child Murders At Robin Hood Hills (produced by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky who went onto make the acclaimed 2004 Metallica documentary film Some Kind Of Monster) is credited with bringing the case to a wider audience. The general consensus amongst those who believe that Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley are innocent is that they were fitted up by the Arkansas police because of their cultural tastes and image; the polar opposite of the Baptist church-going community of a backwater like West Memphis. Echols wore gothic all black clothes, he was a fan of heavy metal, as was Baldwin, while Misskelley – whose confession was cited as a classic example of police coercion – was considered borderline retarded.

The case has been highlighted and supported in the media over the past 20 years by notables in the entertainment industry including Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, Henry Rollins, Marilyn Manson, Natalie Maines of The Dixie Chicks, Johnny Depp (all of whom appear in the upcoming documentary film West Of Memphis and on its soundtrack) and Lord Of The Rings / Hobbit director Peter Jackson, whose close involvement and work with the finer details of the case resulted in new DNA evidence. Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley were eventually released in August 2011 after entering an Alford Plea which meant they could continue to assert their innocence whilst accepting the state of Arkansas still had enough evidence to consider them guilty. This essentially means they have no legal ability to sue the state of Arkansas for wrongful prosecution should they ever be exonerated.

Echols moved to New York with his wife Lorri Davis – whom he married in 1999 whilst on death row. He recently published his mind-blowing and cathartic autobiography Life After Death and, earlier this year, completed work on West Of Memphis with Peter Jackson. Looking for a slower pace of life, in the last few months Echols and Davis moved to Salem in Massachusetts. Arguably the east coast’s answer to the liberality of San Francisco, it’s home to America’s more esoteric religions and is renowned as a spiritual centre. But the irony of relocating to a town synonymous with 17th century witch trials isn’t lost on Echols: "the witch trials are a huge part of the history here and just because of that, it became a mecca for alternative forms of spirituality, religion, practices and anything in that vein," he says. "I can walk one street over from my house and get acupuncture. So it’s like the one place in America where I’m in the majority."

Spirituality and books are the two things that kept Echols alive on death row. Because of the ongoing nature of his case and its high profile, a date was never set for his execution. However, surviving the alleged abuse by prison guards and the inhumane living conditions is enough to weaken even the sharpest minds and fittest bodies. During the early years of his sentence, Echols was a voracious reader, working his way through thousands of books – more than most people would read in a lifetime – but the long-term effect of no exposure to sunlight irreparably damaged his eyesight. During the last few years of his sentence, he exclusively read about spirituality, building on his Buddhism, which he embraced in the late 90s. He became adept at meditation as a means of closing himself off from his terrifying surroundings.

"By the time I got out I was sitting for anything between five to seven hours a day," says Echols. "While I was in I received ordination in a tradition of Japanese Buddhism – the same tradition they used to train the Samurai in ancient Japan. On death row there is no medical care or dental care – they’re not gonna spend money on someone who they’re planning to put to death; they see it as a waste. So there were times when I was really sick or in extreme amounts of pain. The only thing I had to turn to was the energy work, the Qigong, Reiki and meditation. That’s what I focused on to help with the pain, to keep myself intact as much as possible and keep myself from going insane."

In Life After Death, Echols describes the deplorable living conditions which death row inmates suffer inside super-max jails, along with allegations of rape, abuse and serious physical violence from guards. Prisoners are fed a diet of carbohydrate mush: overcooked rice or noodles with no fresh veg and no fruit – because of the risk they could ferment it into alcohol, which as Echols relates, some prisoners might do in a toilet. It’s a diet that, along with the inactivity of solitary confinement for 24-hours a day, makes diabetes rampant. The only way to stay fit is for prisoners to motivate themselves to get up and exercise.

The violence and unhealthy diet which Echols documents in his book make such super-max prisons sound no less severe than Abu Ghraib. It’s a wonder such places aren’t accused of contravening human rights. "Yep, but most people in the US don’t care," says Echols matter-of-factly. "They have this attitude that if you’re in prison you deserve whatever happens to you. A federal inspector did come in and look inside the prison – the super-max where I was – and he said it was the worst conditions he’d ever seen in a prison outside of Guantanamo Bay."

Inside his cell, Echols had just enough room to do push-ups on the floor. But keeping fit physically is only part of the battle and the reason Echols embraced spirituality whole-heartedly. "It was not just about physical survival, but psychological survival – keeping your sanity," he says. "You live in fear 24-hours a day, seven days a week. You never really rest or sleep very deeply. Every single minute is either psychological, spiritual, emotional or physical torture. Sometimes all of them at once. I dealt with that fear by meditating. For most people it just wears them down. People come in and you see them physically and mentally deteriorate really rapidly. They snap and go insane. When you’re in prison, if you’re constantly looking down the road to a day when you might get out and you’re always anticipating that, and that’s what you live doing every single day for years at a time, you’re going to go stark raving mad."

Echols was fortunate that his case received such notoriety. As he says, having all the evidence in the world pointing towards your innocence is only half the battle when a jury has already decided your guilt. He claims inmates who were innocent were put to death whilst he was on death row. The DNA of a particular convict apparently didn’t match that at the scene of the crime. "In the US, those who will be executed or kept in prison for the rest of their lives are a tiny fraction of the people in prison. Most of them are going to get out one day. So when you put them in these extreme conditions and drive them insane, that’s probably not a great idea. Drive them insane and then let them back out into society? You’re not hurting anyone but yourself in the end."

It seems evident that Echols’ case is part of a bigger problem. "That’s what I keep telling people," he says. "This case is nothing out of the ordinary; it happens all the time. Most people just aren’t fortunate enough to have a camera in the courtroom to capture it on film. But it happens in every state all over this country ever day and people just never see it. "We just got lucky."

The majority of US states still have the death penalty as a legal sentence: the number is currently 37. "It’s primitive. Barbaric," he says. Even if the person who Echols thinks really did commit the murders were brought to justice, Echols still wouldn’t want to see him executed – even after what he went through. "I don’t. Even if it’s 100 per cent hard fact. If they’re executing this guy then they’re going be executing other guys and some of them are bound to be innocent. I think if you have to do away with something like that just to save the innocent lives then that’s what should be done. There has to be some sort of real rehabilitation. Not just lip-service that politicians give to the matter. I was in prison for almost 20 years. And in that time I never saw even the slightest shred of any rehabilitation programme – anywhere in the Arkansas prison system."

Echols’ own personal rehabilitation has been helped by the support and reception he’s received while travelling around promoting his book and, more recently, West Of Memphis. He appeared at the Sundance and Toronto film festivals this year where the film was screened ahead of its release this month. "Every time we’ve got standing ovations," he says of the film’s reception. "People have said, ‘I’m so glad you’re out, I’m sorry for what happened to you’. It’s been 100 per cent positive." Work started on the film in 2008 – two years before Echols’ release – following the judge’s refusal to reopen the case to hear the new DNA evidence. So in essence, West Of Memphis was produced to present the case that would have been presented in court.

In Life After Death Echols suggests how the lack of freedom that goes along with celebrity – such as in the case of his friend Johnny Depp – would be as bad if not worse than being in prison. Ironically, owing to the high profile nature of the case, Echols is now something of a celebrity himself. Since the release, he’s been interviewed by Piers Morgan on US TV, he introduced Marilyn Manson at the 2012 heavy metal Golden Gods Awards in LA and he recently appeared with Henry Rollins at the end of his recent spoken word tour. Even while still inside prison, Echols co-wrote the song ‘Army Reserve’ with Eddie Vedder for Pearl Jam’s self-titled 2006 album. He also collaborated on the album Illusions in 2003 with ex-Misfits vocalist Michale Graves.

With his continuing high profile comes the inevitable dissent. The internet is rife with people who think Echols is guilty of the murders. "You’ll always have people like that – who don’t have all the information," sighs Echols. "People who make stuff up as they go along. Even if Terry Hobbs [stepfather of one of the murdered boys, accused of being the real murderer by Natalie Maines of The Dixie Chicks, whom Hobbs then sued for defamation] were to stand up and confess, you will still have people who will say it’s not true. I just get on with my life. If they don’t accept concrete physical evidence such as DNA testing, there’s nothing I can say that’s ever going to sway them in any way."

Whether Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley will ever be exonerated remains to be seen. "According to the state of Arkansas, the case is now closed," says Echols. "Everything we’re doing is to bring more pressure on the state to get them to reopen the case. We’re still doing investigations – we’re still trying to get files from the FBI – there are about 200 pages of documents we’ve never seen before. But the West Memphis police department’s prosecutor’s office is fighting that. They don’t want us to have it."

Life After Death is available now in the USA, published by Blue Rider and out in the UK in June, published by Atlantic. West Of Memphis opens on 21st December

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more