In the six-year time span between their debut single (1981’s ‘Dreaming Of Me’) and the release of a mighty sixth album, Music For The Masses, Depeche Mode went through a major artistic metamorphosis. Throughout this period I’d been a huge fan and part of the attraction was the ease with which I could relate to their transformation. In 1981, as an 11-year-old, I was still very much a child, eager to please all and sundry. I hadn’t worked out any of even the most basic fundamentals of who or what I wanted to be. Likewise, Depeche Mode’s early singles were bouncing, bippety-boppety synth-pop that possessed innocence and an almost childlike naivety.

By 1984, they’d released the ‘Master And Servant’ single, which nudged and winked a path towards S&M, but ensured the band looked faintly ridiculous clad in bondage gear on Top Of The Pops. I think of it as Depeche Mode’s awkward teenage phase and it coincided with me being 14 and beginning to become aware of my sexuality, but without any idea of how to express it. I’d met my very first girlfriend, but she would only let me kiss her if we played Michael Jackson’s ‘Billie Jean’ in the background (which, in retrospect, was very wrong on an infinite number of levels) and with the lights turned off.

I was 17 in 1987, an age that lies on the cusp of adulthood. It was harder to blame my mistakes on youthful bluster and, looking back, was a stage at which I craved a sense of direction and purpose. Depeche Mode were a step ahead of me – 1986’s Black Celebration, a record I adored, had begun the process of redefining the band’s sound, but it was Music For The Masses – released in the September of 1987 – that delivered a suite of songs which cemented their burgeoning maturity and confidence. Depeche Mode had grown up. Unlike me, they’d left their gangly pubescence behind.

Music For The Masses was a defining release for Depeche Mode, and America in particular gorged on its charms. By the end of the album’s promotional tour, the four boys from Basildon – whose debut single had stalled at number 57 in the UK charts – played a show to 70,000 fans at the Pasadena Rose Bowl. That’s quite a step up.

With Music For The Masses, Depeche Mode seemed to have grown into their sonic skin. The signs had been there for a while – I’d loved their criminally underrated 1985 single ‘Shake The Disease’ and felt Black Celebration was their best album yet. However, Music For The Masses pushed them further into new territory. The use of sampling was drastically reduced (there are only so many times a band can make the recording of a hammer hitting a pipe sound interesting), while experimentation with synths and an increased use of guitars and drums nourished Martin Gore’s dark and clever songwriting.

By early 1987, Gore had moved back to London from Berlin, but not before soaking up the German city’s club scene, while keyboard player Alan Wilder had released an experimental solo album (1 + 2) under the name Recoil, which showcased a love of minimalist artists such as Philip Glass. Singer Dave Gahan had become a father for the first time, so the creation of Music For The Masses became a three-step process; Gore would write a basic song structure, Wilder would then arrange the music and the full band would add the final flourish in the recording studio. The end product was a tougher but richer sound, described by Gahan as “electronic metal”.

The album was recorded at Studio Guillaume Tell outside Paris and, significantly, without the direct input of producer Daniel Miller, who had worked on all five previous Depeche albums. The arduous Black Celebration sessions had brought the band’s relationship with Miller (who also ran the Mute record label) to breaking point and fresh ideas were required.

Depeche Mode turned to Dave Bascombe, who’d impressed with his work on Tears For Fears’ blockbusting Song From The Big Chair. The change of producer (although Wilder would subsequently claim that Bascombe played the role of engineer rather than producer) ensured the recording sessions were relaxed (even if Andy Fletcher dubbed Paris ‘Dog Turd City’) and inspired the title of a video documentary – Sometimes You Do Need Some New Jokes – included with the album’s 2006 re-release.

The first track that saw the light of day was lead single ‘Strangelove’. For me, it’s one of the album’s two weak tracks (the other being the misfiring ‘Sacred’) and sounded like a dot-to-dot Depeche Mode song bedevilled by a clunking chorus. However, the next single more than made up for any concerns I had about the Mode’s new material. ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ was absolutely mighty. It’s still my favourite Depeche Mode song and the felt like the perfect fusion of a huge synthesized riff, arena-sized beats (the track incorporated a Led Zeppelin drum sample) and a delicious chorus. Gore’s lyrics were a heady mix of drug references and homo-erotica and ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ would quickly become one of the band’s biggest live performances.

The promo videos for both singles were directed by Anton Corbijn, who had previously worked with them on their ‘A Question Of Time’ single. Put simply, the Dutch filmmaker brought Depeche Mode a slug of credibility. Shot in grainy black and white, and featuring central female characters for the first time in the band’s video history (although they were all waifish models, so it was hardly radical feminist art), both videos looked fantastic. “I think Anton saved us, visually,” Gahan admitted on Sometimes You Do Need Some New Jokes.

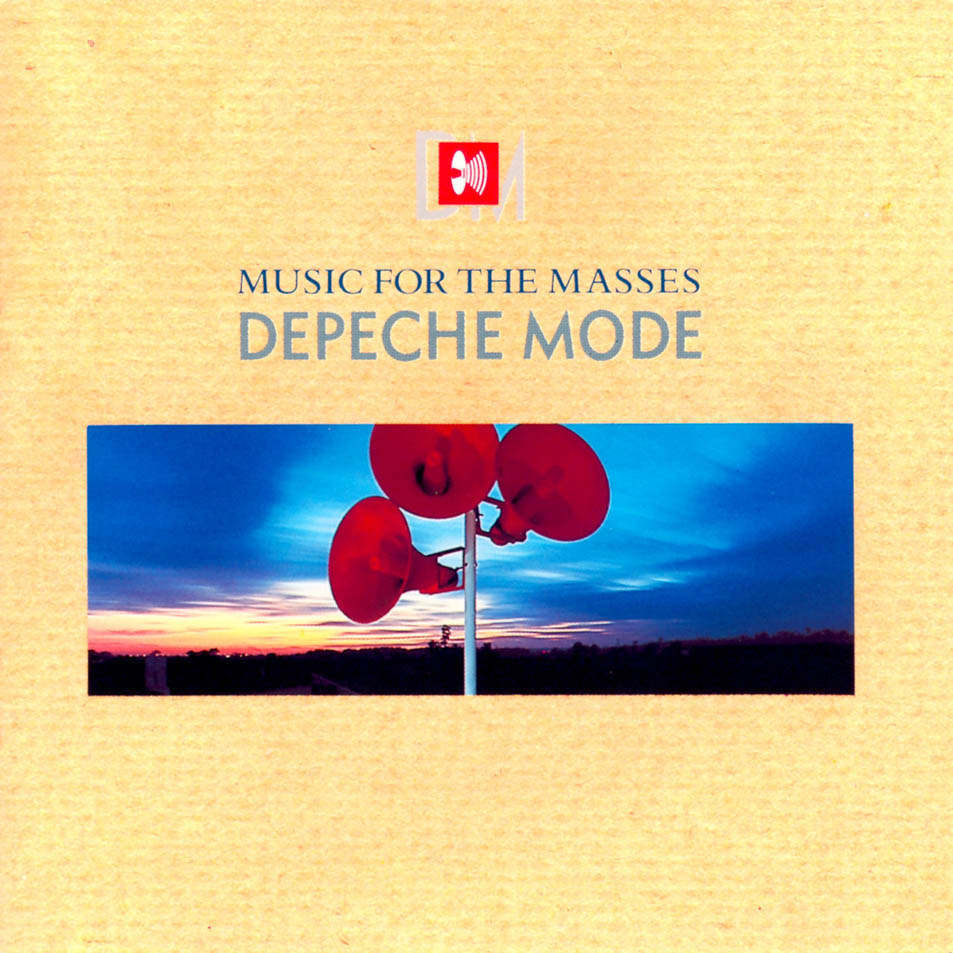

The artwork for Music For The Masses was pretty smart too. I bought the album on geektastic limited edition transparent vinyl (although my copy had a nasty black smudge entombed within its loveliness) and the cover was a sleek design by artist Martyn Atkins who created his “propaganda and open spaces” concept using East German motif imagery and landscape photography of the Peak District.

But, even with some neat packaging and with Anton Corbijn as a champion, it was the songs that made Music For The Masses so special. Martin Gore had become a luminous songwriter. The two tracks on which he provided lead vocals highlighted his ability to write songs from a very personal place and work them into anthems for a stadium of fans. ‘The Things You Said’ was an intimate eavesdrop on an end-of-relationship conversation. “I’ve heard it from my friends/ About the things you said/ I’ve never felt so disappointed” he sang, defeated and dejected. Even better was the sex-pestering ‘I Want You Now’, on which Gore laid out his carnal wish-list against a backdrop of wheezing accordion sounds and samples from porn movies.

That’s not to say that Gore kept the best songs for himself to sing. With Gahan on lead vocal duties, Music For The Masses played out its beautiful balance between edgy experimentation and giant pop songs. The chorus-less ‘Behind The Wheel’ pulsed over a simple repeated chord pattern (I’d take great delight years later when Depeche Mode would be cited as an influence on techno), while aping the ‘Big Sky-driving’ songs that would sit so well with an American audience. The jittery ‘Little 15’ was inspired by Michael Nyman’s score for the Peter Greenaway film A Zed And Two Noughts, while ‘To Have And To Hold’ was sinister electronica with Gahan confessing a lust for salvation. Easily the album’s oddest track was the closing ‘Pimpf’, which began as an eerie Wilder piano refrain before descending into crashing metallic samples and doomladen chanting.

And if Music For The Masses managed to sound good on my absolutely shit (thanks, Sir Sugar) Amstrad, it birthed a thrilling live show. By January 1988, the album’s promotional tour had schlepped to Manchester’s cavernous G-MEX venue. Ably supported by Hard Corps (whose singer wore a totally backless outfit – and I mean totally), Depeche Mode had perfected their electronic metal show, even if Gahan flailed around like a marionette after too much Sunny Delight and Gore looked like he’d raided the S&M section at H&M.

But, even then, the band’s fanbase was a bit of a mystery to me. None of my school friends liked, or at least admitted to liking, Depeche Mode. I’d never – and still haven’t – met anyone who would describe themselves as a huge fan, but here they were selling out a 9,000-seat arena. The Mancunian woodwork must have been frightfully empty that night.

However, slowly and surely by word-of-mouth, America were starting to truly ‘get’ Depeche Mode, and the band began to nuzzle into the ‘post-college radio’ stratosphere inhabited by REM and U2. Music For The Masses entered the Billboard Top 40 (a first for them) before eventually selling over a million copies in the US alone. A thirty-odd date North American tour was captured by legendary filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker on the ground-breaking 101 feature-length documentary. Pennebaker would beautifully portray the grind of touring, set against a faintly bizarre sub-plot featuring of a bus-load of Depeche fans following their heroes across the continent.

The climax of the Music For The Masses tour (and the documentary) was the 101st show at the venerable Rose Bowl in Pasadena on June 18 1988. Supported by OMD and Thomas Dolby, the band played to their largest ever audience. The gig felt like a landmark – Depeche Mode had somehow managed to become one of the biggest bands in the world even if few folk would outwardly confess to liking them. I loved Depeche all the more for their achievement.

On the Sometimes You Do Need Some New Jokes film, Martin Gore recalls how he named the album with a “tint of irony". The awkward, uncool Depeche Mode were never supposed to make music for the masses. Their next album, 1990’s stadium-ready Violator, would sell over four million copies and spawn two global anthems in ‘Personal Jesus’ and ‘Enjoy The Silence’. Depeche Mode had grown wise beyond their years – Music For The Masses had fulfilled its own prophecy.