“When I think of you, everything goes crazy”

Libraries give you power. Step in when your teachers are too busy fiddling ‘Dixie’. Some blessed loon on the staff at Cov Central Library in the late 80s decided to take charge of my musical education. I’d have my mind blown by Melody Maker of a Wednesday morning, then by Saturday morning I’d be rifling the racks, in the remarkable record section that could TARDIS you anywhere/any time in the musical universe, in a building that used to be the Locarno Ballroom (as immortalised in the Specials ‘Friday Night, Saturday Morning’).

This wasn’t just a curated cannon of classics; they’d have everything from the authorative to the apocryphal. Hairway To Steven, Throwing Muses, Isn’t Anything, Surfer Rosa, Daydream Nation, The Young Gods – those records from 87/88 that seemed to unlock the world.

Whoever the kindly stock-buyer was they’d also help you out when you were following trails BACK in time from those records, Nick Drake, Durutti Column, John Martyn, Kevin Ayers, Minutemen, Meat Puppets, PiL, King Tubby, Roxy, Eno, Bowie – everything you needed to figure out where the fuck this stuff might’ve come from and where it might go. So when I read a review of A. R. Kane’s ’88 album Sixty Nine and started having dreams about the sound conjured up by the writers words, I knew that Cov library would, without me telling them to, GET it for me, let me hear it, and then let me hear the names A. R. Kane were dropping. Miles, Arthur Russell, Ornette, Pharoah, Coltrane. When you’re 15 and you hear this stuff your mind never recovers. And as an Asian into an avant-garde indie music made by and for an overwhelmingly white group of music makers and listeners A. R. Kane were even more important as figureheads, as proof that this shit should have no colour code. In their own way, in my memory banks they stand as mighty as Prince: not just inspirational for what they made but for who they were, a leonine isolation you could try and get near, warm your old frozen-out bones next to.

“You just unfold it’s just a tumble with a little caress”

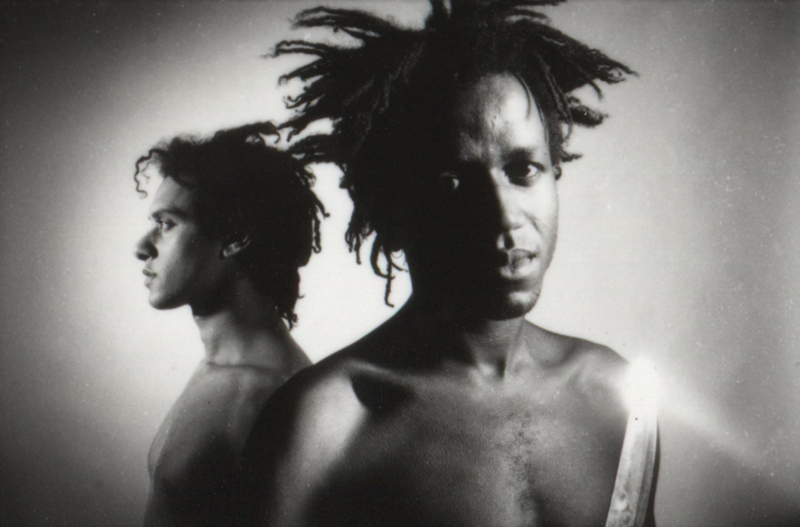

What I could deduce was skeletal, suggestive: A. R. Kane were two East Londoners called Alex Ayuli and Rudy Tambala. Alex was one of the very few black advertising copywriters in the biz. In 87, as collaborators with Colourbox on the M/A/R/R/S single ‘Pump Up the Volume’ they found their strange arcs of guitar and noise being part of an international number one smash. Other than that all you could be sure of was that they denied having any influences beyond Miles Davis, and they made records that sounded like no-one else. Sensual, spiritual, vaporous, liquid, unearthly, subterranean. Most of their work was self-produced; some of it was recorded by Robin Guthrie, the Cocteau Twins’ guitarist who was obsessed with the band. The political hold was important – it was astonishing to me to hear black/Asian musicians playing this kind of music but for a long time I was happy to keep my knowledge of the band half-formed and mysterious. Luckily, A. R. Kane both seemed just as keen to not talk about their backgrounds.

Half a lifetime on, their ever-new, always astonishing music is getting reissued by One Little Indian in the form of The Complete Singles Collection. This sumptuous, indulgent set collects every single A. R. Kane ever made and is something like heaven, a two hour suite of unblinking fearlessness and vision, an essential launch-pad for anyone’s understanding of some of the best music of the late 80s and early 90s. I ask Rudy Tambala something that’s never been satisfactorily answered for me – where the hell did you guys come from?

“Alex’s folks came over from Nigeria; my dad is African too, from Malawi, my mum English.”

Where did you grow up?

“We grew up in Stratford, East London and were always outsiders (most kids were poor cockneys, Irish or West Indian), but we oozed African confidence and a degree of arrogance – we ruled. We met at Park Junior School at the age of 8 and were close friends for the next 20 years.”

What kind of music did you grow up listening to?

“My mum would play a lot of Strauss, and the radio would play – I remember watching the coloured strip blowy thing in the doorway while Chris Montez crooned “The more I see you …” When A. R. Kane formed we were no longer listening. We were hearing.”

So WHY did A.R.Kane form?

“We were aware of the necessity of ‘flaws’ in music – that was one of the meanings behind the name M/A/R/R/S – these flaws are discontinuities that act as tiny fissures, allowing the dim and distant, diffused gem light of pre-creation to slip thru – it is this that the music existed for – a signpost, a reminder, a note. BTW, that’s a theory. We called it ‘Kaning’ the music. So-called perfect music, whatever genre – aims to remove these flaws, to have a true and complete, finished thing. The flaws leave a space, where the listener can still add something of her own, where she can sit and be. A. R. Kane is one person, comprised of two people. We never had enough individual Kane to make flawed music individually; it needed two of us, working as closely as lovers, in complete trust and proximity. It is telepathy, like children’s marbles dropping from our mouths, laughing, then more marbles, and coloured sticks and rubber bands. Great creators have this within themselves, or else they find a task that creates this at the sacrifice of their sanity. We were never that daring or that great.”

I disagree but don’t say so. Hold on, what do you mean ‘Kaning’ the music?

“Kaning means going to the threshold of creation, of maximum potential where all things are possible yet uncreated, the realm of Lucifer and the Dark angels, the shoreline where angels build sandcastles in defiance of the creator, and knit our world from love and light. Just kidding. Or am I? The creation is not a billion years in the past, it is always just ahead and above, it is our near future. The question is, how much of it do we block, and how much do we allow to become. This is the level of creativity we aspired to, without having a bloody clue. But this is what drove us to make music, as ill-equipped as we were.”

Did the band have a strict line-up of you and Alex or were others involved?

“We worked with a bunch of other musicians and producers and engineers on numerous different tracks – read the credits!”

Oops. What kind of music would you say you were making with your ’86 debut, the ‘When You’re Sad’ single, and how did the hook-up with OLI happen?

“OLI came to see us rehearse, thought we were crap and put us in the studio to record. Maybe cos we were iconoclasts, black, actually quite good, and sexy. Flawed. Our ambitions were to make flawed music and have a good laugh along the way. We had a laugh. We were, as I said, always outsiders. That’s the way it was and is.”

Were people ‘surprised’ when they realised you were the creators of it? (I’m thinking here of the racial ‘shock’ if there was any).

“Don’t know why they’d be surprised by our music; negroes invented rock music, dance music, and free jazz and psychedelia. At least that’s what mama says.”

Despite the ‘sweetness’ melodically of ‘When You’re Sad’ and ‘Lolita’ (the 2nd EP, that came out in 1987 on 4AD) there’s also aggression there, darkness, noise, attitude, a sense of almost hermetic distance from the mainstream. That sweet/sour, love/hate ambiguity is STILL difficult to take (e.g. ‘Butterfly Collector’) – what did you want to DO with your music in those early stages? Change the world, tell the truth, and make a million dollars?

“We were being true to our telepathic instinct and aesthetic sensibility – that is what we served. The flaw. We were not reactionary. Love never featured, except as a medium for the flaw and the fabric of the universe.”

How did the 4AD hook up occur for the Lolita EP? Was Robin Guthrie someone the label suggested or someone you asked for?

“Robin was the perfect flaw-engineer. We chose him and he chose us. There was a lot of choosing going on. ‘Lolita’ was written in a batch of seven demo songs along with ‘When You’re Sad’, not after – it obviously needed a different treatment – one cannot always fuck in the same way. What chaos – it only appears like that from the wrong angle. We created flaws. Boring for you, I know – but what can I say? We worked – initially – as one individual, A. R. Kane – democracy is mediation – we did not mediate, we allowed creation in, by knowing when to get out of the way.”

Oddly, for a band who’d topped the charts, success seemed to be something A. R. Kane never cared about at all. They seemed to be more concerned with enacting a revenge, a terror strike against rock’s limitations, a reaffirmation of a very non-80s, more ancient and deranged love. How instinctive was A. R. Kane and how intellectual? Lyrically the Lolita EP’s deeply disturbing – is that cos you were emerging/within a deeply fucked-up relationship at the time or was that a conscious effort, to make the EP’s lyrics have a narrative flow and thematic focus?

“It was more intuitive than instinctive, and Mr Kane is very well read, too. ‘Lolita’ is not disturbing; it’s just a record of certain states and misunderstandings, and issues that occur from time to time in EVERY relationship. We used this medium to create flaws, the damaged lovers. Perfect metaphor that transcends itself, birthing another, acuter metaphor, a fugue-a-phor. But yes, and yes, pinning things down, closing fissure, the end of creation. Death. It was always there. Some people got it immediately; theme as metaphor, as carrier signal. Not a lot.”

Before Kevin Shields even dreamt of using a breakbeat, A. R. Kane seemed to be as informed by hip hop and R&B as much as anything else that flowed into their dream pop. They never seemed like a band who had a ‘problem’ with the way sampling technology and sound engineering were progressing in the 80s – they’d uniquely found a way to utilise all that kit and to still preserve a rawness and spontaneity. And that’s why it’s so hard to find genuine descendants from their sound (the only real one I can think of is Disco Inferno), only antecedents (Hendrix/Miles). Did that fearlessness come from your love of hip-hop/dub/electronic music and if so did it ever occur to ‘drop’ the guitars from your music altogether. You didn’t, why not?

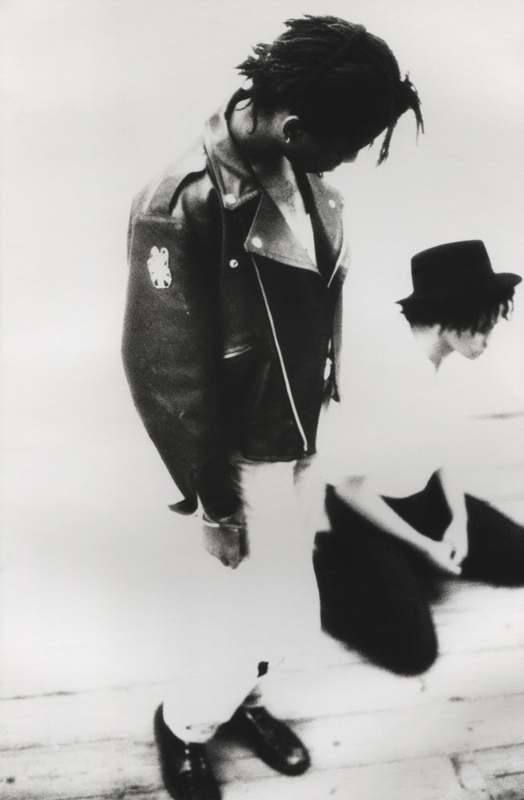

“The influences you cite and others (Can, Tangerine Dream, The early electronics like Human League, Japan… Kate Bush, Marvin Gaye etc.) did inform our choice of tools, and we love guitar, too. Yes, capturing that mystery – the unfinished object, the flawed art. In a way, our live performances were more flawed than the recordings – once, and never again – just once… this is so final. I felt it sometimes. I saw it in the faces at the front. Religious ecstasy? No. But definitely a glimpse… gem light? I had it watching Sonic Youth and listening to Kind Of Blue. It’s never the same twice. It is three times.”

There’s something just downright BIGGER about the Up Home EP in 88, on your new home, Rough Trade. What happened to the A. R. Kane sound from 87 to 88 and were you recording Sixty Nine concurrently with it? The three EPs you released that year, together with this album makes for one hell of a body of concentrated work.

“Up Home was special. Something happened. I can’t explain.”

Did you believe your own hype? The press, at least some of it, was entirely rapturous.

“We were very lucky, we used to sit in bars, and stare wide-eyed at each other and laugh like spliff-heads, just cry with laughter for ages, saying, ‘What the fuck is happening’, and we knew it was not our doing, it was just that, it was happening, and we enjoyed the trip, with no sense it had ever started or would ever end. We were in an altered state for a few years. Drug-free, I hasten to add. Well, mostly. Fame caused rifts with our friends – we ended up spending more time with creative types, musicians and the like. I never met any of our fans, except the sexy ones.”

How isolated did you feel?

“We were not exploring territory, as you put it. Why would we? Where we were was not a created place. Guess you could say we were creating territories? No-one else went there or knew how to or how they should want to. Even I can’t go there without being alone. It was a one-person thing. All people are unique.”

Were you conscious of being in some sense ‘figureheads’ for black & Asian musicians who wanted to slip the usual soul/funk/reggae strangleholds & stereotypes? Cos you were man, and still are!

“Yes. A lot of people we knew that felt the constraints of normal society used A. R. Kane as a cue to break free. It was quite strange in a way, because we never did. I think that many imitated the form that they perceived, with the desire for acclaim and success. Bollocks really. But from that there is the possibility to find your own style, form. To innovate. That happened sometimes, I reckon. Catalysts remain unchanged. So we weren’t catalysts. But we never got why others didn’t get it. Until we didn’t.”

After Sixty Nine, AR Kane continued in an even poppier, slicker direction. The double-album i that emerged the following year (1989) is a kaleidoscope of ideas, mostly hit, occasionally miss that sprawled over two discs and contained what sounded like a new blueprint for pop, in some ways the most simultaneously disciplined yet wayward A. R. Kane record yet. Is it too pat to see 88’s Love-Sick EP as the bridge that pushed you towards the shinier, in some ways more hysterical textures of i?

“We kinda broke into the candy store and went mental with Love Sick and i – somebody should have stopped us! We had more money to buy music and we were exposed to a lot more through recommendation and just through hanging out in different scenes. The indie scene was new to us; I thought indie meant from Indianapolis. Our first bass player Russell introduced us to a lot of ‘dark’ music (Swans, Buttholes, Nick Cave) and our second bassist Colin introduced us to certain classical ideas and progressive, intellectual stuff.”

Were you both already sensing that the band wasn’t going to last forever with i. Hence the double-album length, the need to absolutely say everything you wanted to say musically before the inevitable drift-apart would occur?

“We just did what we did with i. Somebody should have stopped us. No, not really. It was a trip – Geoff Travis accused us of being obsessed with the process. Still no idea what he meant. It should have been a triple album. 1,2,3. But we ran out of tape.”

I loved all the tiny musical ideas you put in as well, the short tracks, very much reminded me at the time of the way hip hop albums had ‘skits’ to hang the thing together, make it an engulfing whole you wanted to listen to front-to-back. What was keeping you together/pulling you in different directions at that point? Geography or artistic differences? Alex has spoken in the past of wanting to ‘escape’ the ‘London scene’ – were you both just finding the pressure/lifestyle too strenuous/crazy? A need to reinstall discipline in your life?

“Telepathy is necessary to create one person from two people, to serve the making of flawed art. Our telepathy was extremely short distance. It broke over distance – geographical, temporal and emotional. When it’s gone, it’s never really gone. But the happening and the time for doing, the time-bound events, they pass on and up and over. Kane grew up. And down. We never really learned to walk on our own. The A. R. Kane period was a gift, and we were carried. Maybe Kane never really grew up; maybe he’s still sitting on the rug, waiting for a hand up?”

The way that i seemed to shoot all of A.R. Kane’s bolts in one glorious surge meant that New Clear Child, their last record, is a curate’s egg. You got the sense, listening, that Rudy and Alex were too apart, & consequently the recording process too bitty & piecemeal to make a coherent album.

“New Clear Child is a mutant, more special than I realised at the time. It came close to standing, but it stumbled, and glossed the grazes. A few of the tracks are really there, but as an album it painted out some of the crucial flaws. Time creeps into the spaces and they crystallize. Everyone knew it. We knew it. Still, there are some ways through on that album, and I love them still.”

In the time since that swan-song have you listened to A. R. Kane much? Have you heard your influence on anyone? What led towards the reissue of the singles now, nearly 20 years on?

“I hear similar stuff, sometimes obvious, some coincidental. Don’t really care. I received a bunch of messages over the years asking for tracks so I asked OLI to make the album. Eventually they said ‘OK’, and that’s that. It seems right, feels right to release it now. Kinda like a juncture, a flawed time.”

Are you in contact with Alex? Is there any possibility or need for you to work together again?

“I’m not hearing from Alex these days – he’s doing his thing somewhere, some music I think. I don’t know if we’ll work together again, who knows. I’m working on several songs with Alison Shaw from Cranes, we’ll be looking to find a home for the album and maybe do some live stuff. It’s really great to be working again and with such an extraordinary talent. I feel ‘lucky’, it’s a bit scary. Good scary. Slightly flawed.”

Mostly perfect. If you missed A.R.Kane’s music first time round don’t allow such a tragedy to recur ever again. The future came and went. May it always be with us.

A.R.Kane’s Complete Singles Collection is out now on One Little Indian