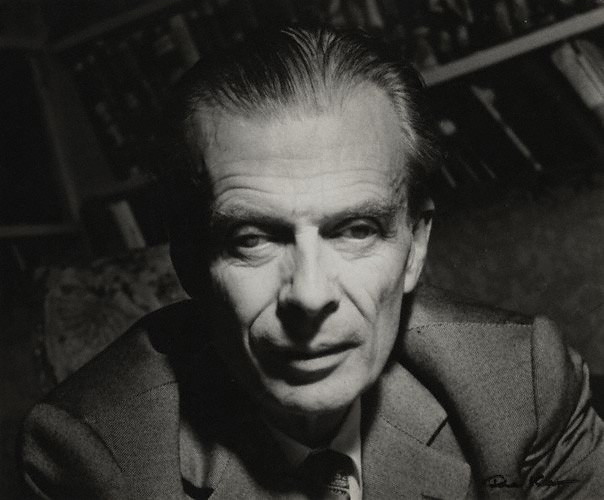

Fifty years ago, in 1962, Aldous Huxley published Island, his final novel. He wrote Brave New World in 1931; it took him three decades to write his response. In a letter to the Maharaja of Kashmir, who after reading Island was inspired to write to Huxley asking where he could obtain psychedelic drugs, he described the book as “a kind of pragmatic dream – a fantasy with detailed and practical instructions for making the imagined and desirable harmonization of European and Indian insights become a fact.” As for the drugs, he gave the Maharaja Timothy Leary’s address.

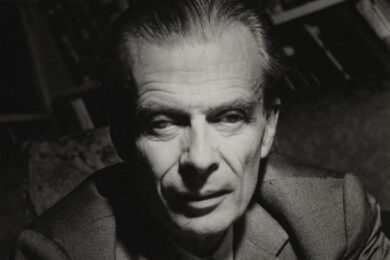

Having first tried mescaline in 1953, written The Doors of Perception soon after and had his first acid trip in 1955, it is safe to say that Huxley was a psychedelics pioneer – but he had long been fascinated by all manner of drugs: there’s even a rumour that, in the ‘20s, Aleister Crowley introduced him to peyote. Whether or not this is true, Huxley was already balls deep in mind-expansion by then; in 1931 he wrote ‘A Treatise on Drugs’, a look at the history of drug-taking, as well as Brave New World, where the panacea drug soma flattens people into numbness. By the time he got around to Island, he’d spent decades researching visionary experience and self-transcendence. Psychedelics were just a part of it, though: Huxley was also into Hindu and Buddhist philosophy – most notably Vedanta, one of the main strains of Hindu thought. The psychedelic experience, as he saw it, offered a powerful shortcut to the liberation from the ego and the understanding of infinite oneness that these religious philosophies guide towards, too, by all accounts.

The idea that an acid trip might be a blissful blast of mystical experience is common enough these days, but Huxley was one of only a handful suggesting it back in ’62. (There was the mysterious Alfred M. Hubbard, who sung the LSD gospel in the ‘50s; Timothy Leary and Ram Dass, known then as Richard Alpert, who were just wrapping up two years of their Harvard Psilocybin Project – Huxley was one of their volunteers; and in ’64, there was Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, galloping around the States, doling out psychedelics.) The near-blind Old Etonian was one of the western world’s boldest early psychonauts, and Island was the synthesis of his investigations. No wonder it took him five years to write – he had a lot to pack in.

Huxley knew it was a patchy novel; after he’d written it he said there was a “disbalance between fable and exposition.” He’s right, of course: the plot and the characters are weak. Pissed-off British journalist Will Farnaby finds himself shipwrecked onto the shores of Pala, the ‘forbidden island’ of South-East Asia, during a stay on the nearby Rendang-Lobo – an industrialised, militarized, oil-rich nation, whose rulers see Pala as backwards in light of its refusal to adopt most forms of technological progress. Will finds, of course, that Pala is heaven on earth.

The plot stays skimpy, but the world-building is rich: the majority of the novel follows Will on a tour of the island, where its perfection throws his grim memories of England into sharp relief. These memories, many of which involve desolately shagging a lover called Babs who lives in a “musky, strawberry pink alcove above the Charing Cross Road,” seem toxic, but they’re also obvious plot devices, slotted in as clumsy contrasts to Pala’s idyll.

So the novel proceeds as an Open Day for Pala – and while most of the characters don’t get to do anything more than stand around explaining how its society works, the ideas are brilliant. There’s a methodical detail about it, as if Huxley asked himself: "How can we create the best kind of people and the best kind of society possible?" Economically, politically, educationally, spiritually – you name it, he’s got an answer. There’s appropriate technology, co-operative economies and free contraception; “the economics decentralist and Henry-Georgian, the politics Kropotkinesque co-operatives”. There are also ‘Mutual Adoption Clubs,’ giving Palanese children about twenty family homes they can roam freely between to avoid the whole ‘they fuck you up, your mum and dad’ thing, encapsulated in a perfectly Palanese soundbite:

“Take one sexually inept wage-slave, one dissatisfied female, two or three small television addicts; marinate in a mixture of Freudism and dilute Christianity, then bottle up tightly in a four-room flat and stew for fifteen years in their own juice. Our recipe is rather different: take twenty sexually satisfied couples and their offspring; add science, intuition and humour in equal quantities, steep in Tantrik Buddhism and simmer indefinitely in an open pan in the open air over a brisk flame of affection.”

If that sounds a bit smug and preachy, well, that’s kind of the tone of Island. It’s not off-putting – it’s just that you’re aware there’s some urgency. Eighty years ago, Huxley was wary of the devouring, dehumanizing machine of technological progress – thirty years and a world war later, he was still banging the same drum. These days, his ideas seem just as relevant; and yet they’re still fringe. Of course they are! Their ultimate goal is happy, evolved humans, not economic growth. There’s a lot of intelligent application of psychotherapy here too, even if some of it is reductive. Huxley’s second wife Laura was a psychotherapist and a big influence; in Island, he’s just as prescriptive, if not more so, about people’s inner lives as he is about the structures that surround them.

The only thing that doesn’t work is his take on overpopulation: there’s a scene in which the islanders explain why they’re happy only having two kids, and tell Will that they use artificial insemination to ‘improve the race’. The eugenicist implications of this are briefly alluded to – Will asks them about the ethical aspects – but it’s brushed off with a firm comment about its clear advantages. This is uncomfortable reading – especially as Island was written in the shadow of World War II and repeatedly refers to its horror – and also given there was such an emphasis on the freakishly cruel stratification by caste in Brave New World. Yet the single-minded pursuit of strong, healthy Palanese people is somehow seen as benign. Neither this discomfort nor the half-assed storyline ultimately detract from the novel’s philosophical punch. On the whole, a Huxleyian utopia even comes out as something to envy – especially if you like your sex and drugs.

On Pala, education in tantric sex – the ‘yoga of love’ – starts when you’re a kid, as do ritual drug-taking ceremonies. Moksha is Huxley’s vision of a perfect psychedelic; a cultivated yellow mushroom that grows in the mountains of Pala. Unlike soma in Brave New World, which is an escape from reality, moksha is a drug that’s meant to bring the Palanese ego liberation – enlightened awareness – neatly reflecting its Sanskrit meaning. A lot of Island is like this, spiritual hints and tips by way of fictional devices. It’s sometimes clumsy, but it still resonates.

There’s a scene where the kids take the moksha-medicine in a ritual ceremony – imagine spending a day at school taking LSD up a mountain with your teacher. It’s heady stuff and brilliantly done. Huxley was never afraid to wade into the heart of spiritual experience – this time via a smoothly syncretized mix of Mahayana Buddhism and Vedantic Hinduism – and come back with a full report. If you’re into spirituality at all, this bit is fantastic; you’ll smell the incense, see the dancing Shiva in your mind’s eye, hear the chanting and a sense of the sacred might briefly arise. It feels odd to read fiction that’s so unreservedly on Team Spirituality, though, and if you’re more secular-minded, it might be a little cringeworthy.

In the final chapter, Will himself takes the moksha-medicine and goes on an epic trip. Some of this is based on Huxley’s real-life psychonautical adventures; in 1955 he took LSD and listened to Bach’s Fourth Brandenburg Concerto; his wife wrote it up in an Erowid-style trip report. This, along with its attendant revelations, is exactly what happens at the end of Island. It’s a rare novel in which the last scene features the main character tripping his nuts off. Words and phrases like ‘infinity’, ‘loving gratitude’ and ‘luminous bliss’ earnestly populate the final pages – by this point, it should make all but the most obstinate cynic bosh the nearest hallucinogen and hope for great things.

Of course, the whole novel has built up to this – to its protagonist and readers sharing in the author’s insight. Not allowing anyone to be swept away, though, Huxley punctuates with a realist’s acknowledgement that the suffering caused by life’s “collective paranoias and organized diabolism” will remain “everywhere, always”. For this, he prescribes not drugs but compassion. Fifty years on, you still can’t argue with that.