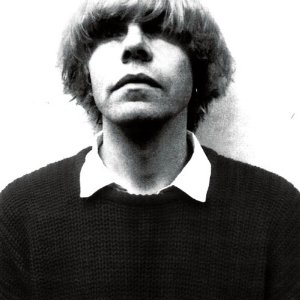

It’s an unlikely partnership: the 45-year-old mop-topped Northwich lad, co-founder of once baggy act The Charlatans, a band who never quite managed to emerge from the shadows of their contemporaries The Stone Roses, hooks up with the almost 54 year old baseball-capped Nashville institution who founded once alt. country act Lambchop, a group who’ve never quite managed to achieve the success that devoted fans and critics have always predicted. Both have been making music in one form or another for a good twenty years, but they’ve pursued markedly separate paths, one distinctly Northern English, one eccentrically Deep South American. And yet the admiration that Tim Burgess expresses for Kurt Wagner is genuine. I should know: there aren’t many musicians who’ve volunteered to sit for eight hours in a cramped furniture truck as I’ve driven from London to Essen, Germany, which is what Tim Burgess did last year in order to see Kurt sing with KORT, a collaborative project with fellow Nashville resident Cortney Tidwell.

At this stage I should declare an interest: for almost a decade I worked with Lambchop releasing their records in the UK, and I’ve also learned that eight hours in a furniture truck is enough to decide whether or not one enjoys the company of a particular individual. (In Tim Burgess’ case, I undeniably did.) But I approached Burgess’ second solo album – its lyrics provided by his unlikely ally, Wagner, and recorded in Nashville by long time Lambchop producer, Mark Nevers – with caution. For all The Charlatans’ resilience, and despite the existence of tracks like ‘The Only One I Know’ and ‘Weirdo’ (songs I danced to as a student but have possibly never heard since), they’ve rarely inspired me, and Burgess’ voice always seemed a little timid. Wagner, furthermore, has carved a lyrical niche for himself with cryptic texts relating intimately detailed moments in his life that have often depended for their impact on the strange, muttering croak of his voice and the smack of his dry mouth. Whether Burgess, with his boyish delivery, could impart the wisdom of Wagner’s poetry was surely questionable.

And yet Oh No I Love You is a resounding success. Perhaps one shouldn’t be entirely surprised – Wagner has previously provided lyrics to Morcheeba, an equally improbable collaboration that developed from a growing friendship between him and the brothers, Ross and Paul Godfrey, who founded the band. (The two songs that resulted, the unusually suggestive ‘Undress Me Now’ and ‘What New York Couples Fight About’, the latter of which saw Wagner duet with singer Skye, remain two of Morcheeba’s finest moments.) Burgess, meanwhile, has grown up, maturing into a far more contemplative individual, his wild days behind him. Wagner, an often circumspect individual, seems to have recognised in his foil a kindred spirit, unpredictable as that might have been to outsiders. So, in a sense, the most notable aspect of this new partnership might be that it underlines the manner in which music can overcome differences in background and method to find a common ground that is both touching and inspiring. To adapt a famous comment by one of Burgess’ contemporaries, Ian Brown, Oh No I Love You confirms that it’s not where you’re from. It’s where you’re at.

Where Oh No I Love You is at, in a nutshell, is Lambchop circa their masterpiece, Nixon, but with that record’s Mayfield soul stylings and Southern country twang transplanted, for the most part, to a small town English bedroom where a young man dreams of making records imbued with compassion, substance and romance. In fact, much of this delightful album resonates with the sound of a man’s ambition fulfilled: one only has to listen to opening track ‘White’ to visualise the grin on Burgess’ face as the song came together in The Beech House, Nevers’ suburban studio. Surrounded by sweet-tempered keyboard lines and exclamations of joy from tenor sax and trombone, all delivered at a cheery pace, Burgess’ vocals no longer seem reticent and shy, his previously mentioned boyish quality replaced by a charmingly humble delivery, his confidence in the song’s strengths more than enough to make him sound utterly convincing. As opening tracks go, ‘White’ is as assured as Prince’s ‘Sign ‘O The Times’, Bowie’s ‘Five Years’, or The Stone Roses’ ‘I Wanna Be Adored’, but its declaration of intent is more modest: it simply announces, "You see? I can do this!"

The rest of the album proves that this confidence sits upon sturdy foundations, something underlined by the fact that Burgess is surrounded by some of Nashville’s best ‘alternative’ players, including guitarist William Tyler and pianist Tony Crow (both of Lambchop and Silver Jews), guitarist and bassist Jordan Caress (who’s played with Caitlin Rose and Justin Townes Earle) and multi-instrumentalist Chris Scruggs (BR549, also Earl Scruggs’ grandson). Their performances are provident, whether on the string-saturated ‘Hours’, the tender ‘A Case For Vinyl’, or the loping, funky ‘The Great Outdoors, Bitches’, and even the presence of a gospel choir on ‘A Gain’ fails to provoke them to flaunt their chops. Only on (ironically, given the title) ‘Our Economy’ does anyone get especially excited, Carl Broemel (My Morning Jacket) reminding everyone of his prominence on Rolling Stone’s 2007 ‘New Guitar Gods’ list by unleashing an old-fashioned, squealing but nonetheless relishable solo as the song reaches its climax.

In fact, Burgess sounds completely at home in these surroundings, unafraid of venturing a falsetto on ‘Anytime Minutes’ and ‘Our Economy’ (where his tone sounds particularly like Wagner’s similar efforts on Nixon), while on the dispirited ‘A Case For Vinyl’ he sounds world weary, his voice breaking amid the quiet crackle of an old LP. The latter is an album highlight – understated and frugally arranged, Tony Crow’s piano the most fluid ingredient present, Burgess’ delivery honest and, consequently, moving – and such tenderness is also on display elsewhere. On ‘Hours’ he finds himself taking on the role of crooner, if a somewhat baby-faced one, as flutes trill and strings swirl nostalgically around him, while it’s doubtful he’s ever sounded so at ease as on ‘Anytime Minutes’. This welcome sweetness is also on show on ‘The Doors Of Then’, but it’s the final track, ‘A Gain’, that provides the ultimate payoff, a perfect counterpoint to the album’s opener. Against a gently strummed guitar, subdued piano chords and the growing hum of an organ, Burgess nudges a slow-motion melody towards an eloquent, intensely personal declaration of love and loneliness, finally accompanied by veteran local gospel group, The McCrary Family Singers, who bring a gratifying spiritual quality to the album’s final minutes, even as they sing "I’ll not brave the dance floor for you".

That the lyrics are not Burgess’ own seems to matter not one bit: though he recently confessed to me that he’s not asked Wagner what some of the songs are about, his delivery is sincere, as though he’s found his own meaning in the words. That ‘White’ could be about the suicide of Wagner’s friend, Vic Chesnutt, <a href"http://thequietus.com/articles/02982-vic-chesnutt-interview-at-the-cut-skitter-on-take-off" target="Out">with whom he engaged in frequent written correspondence – "Missed it all / Missed the ending / Missed the text / We were sending" – makes no difference: it’s no less poignant for lack of that knowledge. Equally, that ‘Tobacco Fields’ aren’t often seen in Northern or Southern England, or even LA, where Burgess spent recent years, doesn’t make the song sound any less credible coming from his lips.

In fact, hearing Burgess sing a line like "Snow on a trampoline" in his deepest voice is an unexpected pleasure, as are other moments where Wagner’s elliptical imagery reaches out from the disc: "I saw Casper the Ghost on your old cereal box", "I realise I’m not Napoleon", "We are now smoking beyond the stimulus package". It’s as if hearing Wagner’s words delivered by this unfamiliar voice, one whose distance from what inspired them allows it to project a more universal sentiment, has revealed their strength even more.

It’s true that, the longer one lives with Oh No I Love You, the more apparent it is that, at its heart, it shares many things in common with its lyricist’s band, and not just a few musicians or a love of country-soul. In fact, it might even be tempting to ask how much Burgess brought to the party: this is a producer’s record as much as anything, stamped with many of Mark Nevers’ trademarks, most notably the purity of the sound and the lack of gimmicks. But Burgess is nonetheless very much the star here. The record overflows with his personality, that of a likeable, unpretentious fan of music thrilled to have the opportunity and privilege to be doing what he’s doing. And it’s not quite such a musical stretch as one might think to have his songs reframed in these surroundings: listen closely and you’ll hear the ghosts of The Charlatans’ more rural flavoured tunes, albeit with bonus fingerpicking, on a track like ‘The Graduate’.

Furthermore, the novelty of hearing Burgess in this fresh context, and of hearing a new voice taking Wagner’s texts to task, lends the whole affair a fresh hue. It’s one that reflects well not only on Burgess but also on Wagner’s aesthetic, upon which Burgess manages to shed new light. Unforeseen as this tie-up must have seemed to everyone around them – and, most likely, to Wagner himself, who seems regularly to profess a humble bafflement at anyone’s interest in his work; and, indeed, to Burgess, who remains in awe of his Nashville cult hero – it proves to be an inspired coupling. It’s certainly worthy of the ten years it’s taken to reach fruition since Burgess once offered to carry Wagner’s guitar after a Manchester show and asked whether he could perhaps blag some lyrics. Don’t you love it when a plan comes together?