1980: Laibach, Born Of Industry

Originally Trbovlje was a very beautiful valley, in medieval times a place for the dukes and local aristocracy to hunt. Later they discovered coal, so they started to exploit it during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and then much more intensively in the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th Century. Gradually the whole area became an industrial area. It was called The Red District because it became a very proletarian, communist area.

Then later things started to degrade and fall apart. They started closing everything, but at its peak Trbovlje had coal production, machine and cement factories, power plants and so on. Power plants produced a lot of dirt and smoke in the Trbovlje valley, so they came to the idea to build a higher chimney. Now you can see this chimney all around the area from the mountains, it is the biggest chimney in Europe and in fact also the highest self-standing structure on the continent.

Some of our fathers were working in Trbovlje factories, and we were industrial socialist children. We ourselves worked in different factories as kids occasionally, so we could earn some money and understand what’s happening in the factories. Our grandparents worked in the mines. Trbovlje now is quite a different city, there’s now a company there producing software for NASA. But I think that it will take a while before Trbovlje will get rid of its industrial feel.

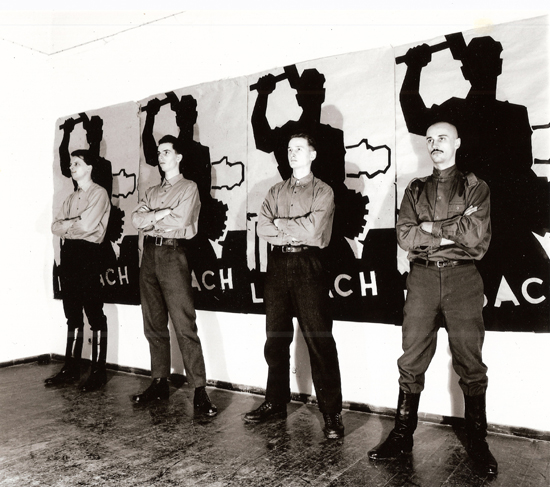

1980: Trbovlje, The Worker’s Cultural Centre. Laibach banned before they even really began

We wanted to do a big event with a concert and exhibition, a kind of multimedia event that was the band’s coming out, in the Delavski Dom Trbovlje. The Delavski Dom is very nice building, with the biggest cultural hall in Slovenia when it was build in 1960: socialist modernist architecture with a touch of Bauhaus.

This was the time in the beginning of ‘80s when lots of things started to happen. First of all 1980 was pretty much a time when – after Tito’s death – chaos entered Yugoslavian politics. Nobody knew what was going to happen and the situation was very tense. In Slovenia we had the punk movement, very important, still anarchic, but it had a strong political appeal. Around punk, there were all these alternative political groups and movements who were trying to establish themselves as the opposition to the dying Communist system.

We covered streets, entire areas with our posters, with the black Laibach cross, which we chose as our symbol. The name Laibach was really stigmatised, being the historic German name for Ljubljana, but used again officially during the occupation time in the War. When we put together the cross, the name and then some expressionist, almost punkish visuals on these posters, it created a heavy image. And all these posters suddenly started appearing in the city. Imagine Trbovlje being a small town, with one main street that was full of these images… At this time Communism did not really allow advertising, so the streets were visually ‘clean’, no adverts anywhere… It was a total shock seeing posters and the event in Delavski Dom was forbidden straight away, described as ‘inappropriate’. The ban was irrational political reaction of the local authorities and Laibach won the first battle.

Laibach, Slavoj Žižek & Slovenian dissidents

There were big reactions after this first thing in Trbovlje, nobody knew much about Laibach at that time, but articles about the banning of the event appeared in the national press. In such political and cultural situation diverse alternative movements were appearing. Slavoj Žižek and his philosophic circle already existed, but they were just starting to become active within some alternative cultural associations. They were quite happy when something like Laibach happened so that they could use it in their theoretical battle of decomposing the Communist system.

Laibach was always very useful material for public debate in terms of freedom of artistic expression and freedom of speech. To a certain degree we ‘knew that we had to produce problems’, so that people like Slavoj Žižek, the Ljubljana School Of Psychoanalysis, and others could debate it. There was a kind of symbiosis between us and other alternative movements in the early 80’.

1982: Laibach’s Manifest

First of all the idea of the ‘stage’, ‘main-stage’ and audience in the modern culture and society (where everybody is a ‘star’ – at least for 15 minutes) is very confusing and debatable; in principle everybody is onstage all the time… Although the ‘original’ Laibach members might not appear onstage anymore – actually they do appear occasionally – they are still connected to the group and work with it as much as they are needed. Laibach ‘refuses’ the concept of originality and understands the notion of ‘original members’ as obsolete.

Already in our 82′ manifest/program we have clearly defined the principle of the (collective) work of the group (items 1, 4, 5). A group is first of all a collective mechanism where members have to leave their individual projections and frustrations aside. They have to submit, or even better – ‘exclude’ individuality in order to accept the functionality and complexity of the ‘higher’ system. In such mechanism every particle is important but it is also interchangeable. Laibach always was, and still is, an organism whose life and means of activity are higher – in strength and duration – than the goals, lives and means of the individuals which comprise it. It self-reproduces itself as an idea, and constantly mutates organically as a progressive virus.

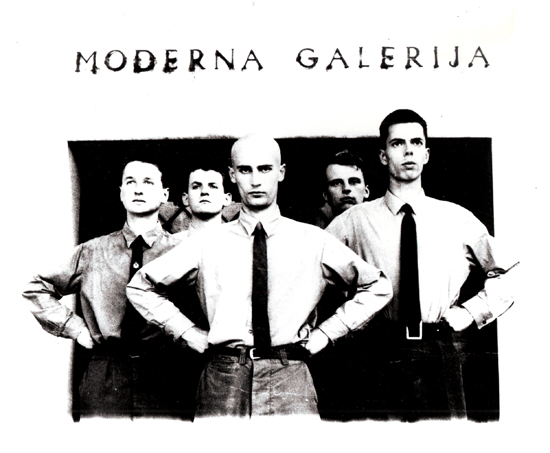

Early 80s: Laibach’s Military Service

Military service was an obligation in communist Yugoslavia and we all went to serve the army. Of course we had uniforms, and as a soldier you could occasionally go out in them. It was quite a ritual – soldiers were walking up and down the city centres in uniform trying to talk to girls and getting drunk, fighting with local boys… Most members of Laibach were serving military service in other parts of Yugoslavia than Slovenia, like in Serbia, Macedonia, Monte Negro, Croatia, Kosovo or Bosnia.

A member of Laibach, who served military service in Belgrade would occasionally escape from the barracks, dressed as a soldier, only with added Laibach cross – a badge on the uniform. He was going to punk and other alternative and cultural events, concerts. People thought that this uniform was his regular ‘punkish’ outfit.

So the idea to use uniforms was there at the very beginning. When one of the members left the army he had a chance to take with him a few military uniforms, stolen from the magazine. He took them directly to the Laibach concert in Belgrade and dressed the band in these new outfits for the show. It was in tradition of groups like The Beatles and Rolling Stones, The Monkees and others; all these groups had a sort of official uniform at their beginnings. In the Yugoslav army there were musicians who had to play music in the officer’s clubs and so on. Bands were dressed in military uniforms performing either jazz or rock standards and then mixing it with military songs. Other armies had (and still have) such bands.

So, as a Yugoslav rock band, we started to wear authentic Yugoslav military uniforms. Our only addition was the Laibach badge with the cross on it, that was it. A new uniform was born. In a different context it worked horrifically well.

We also smuggled out some smoke bombs. At the beginning of the ‘80s it was hard to get stage hazer or smoke as an additional effect to the show. So we simply used these camouflage smoke bombs. They were not very pleasant for the eyes, but they looked really great; you could see absolutely nothing for a while… The first time we used them was in Belgrade, which actually was the ex-army officer’s club, turned into a student cultural centre. It was a disaster because of the eye pain and tears, but the band insisted on continuing to play on stage. Unfortunately, the audience was not so fanatic and escaped out of the venue. It was all very funny and heroic at the same time.

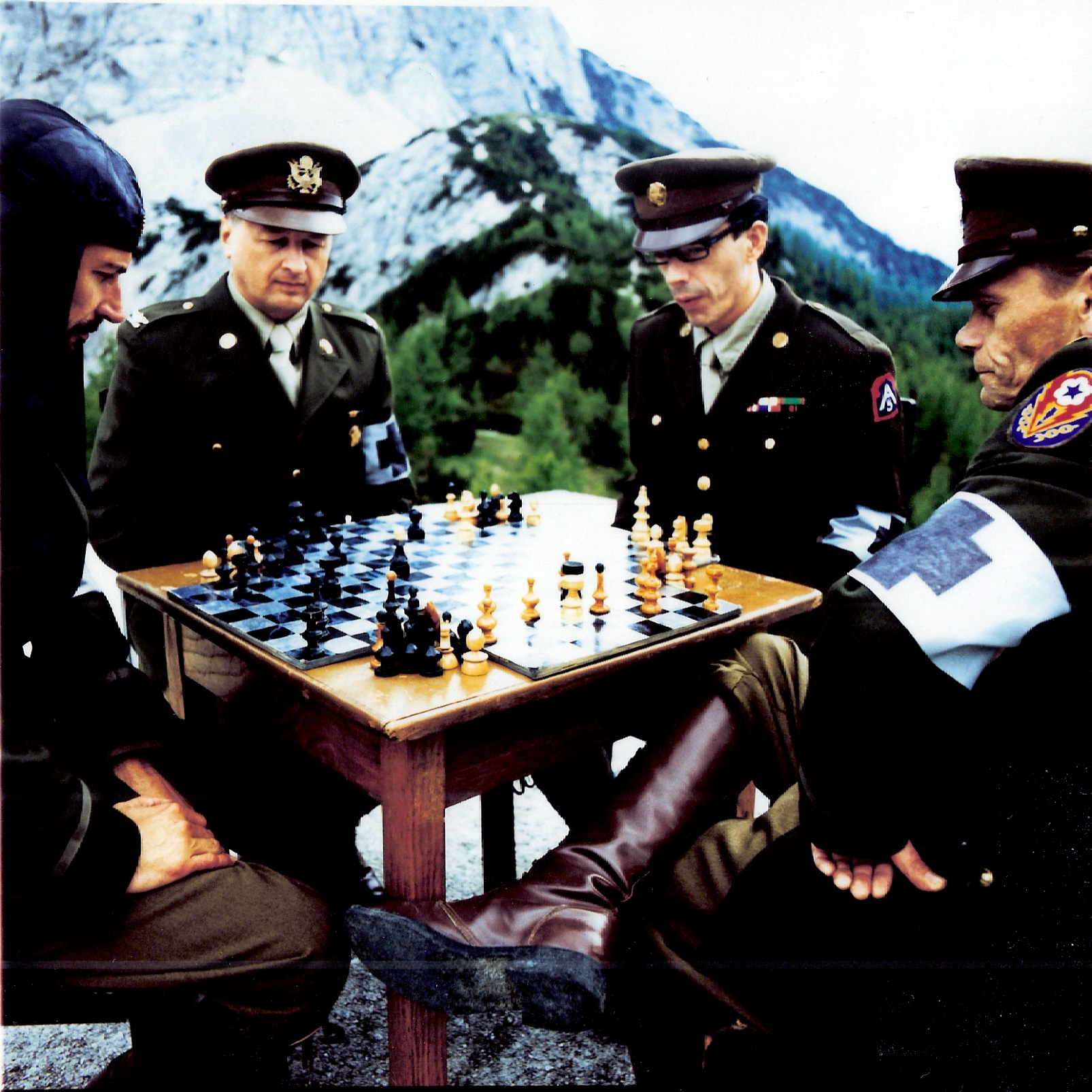

1983: ‘We Are Forging The Future’ performance- 12th Zagreb Music Biennial, Moša Pijade Hal, Zagreb

The Zagreb Biennial was a really great festival, all the important composers of the ‘60s and ‘70s performed there, Cage, Stockhausen; everybody doing their experimental classical or acoustic and electronic performances. It was a very serious festival, and we said, ‘This is a nice context for Laibach, we are doing kind of experimental, classical thing as well, let’s try to get on the program.’ We invited our fellow British groups 23 Skidoo and Last Few Days, and played this all night concert. All three groups, but especially Laibach in military uniforms with black crosses and industrial music looked completely different from the rest of the Festival. During our heavy industrial concert we projected historic 35 mm film footage of Yugoslavia’s economic and political history and then on top of it we had Super 8 projections of some selected porno loops. Of course this was an immense problem because the film was about this happy country of Yugoslavia, socialism and Communism, workers, factories, political rallies, and then you had these brutal porno scenes projected on top… In the context of the festival’s ‘youth’ event this was a bit too much for everybody and the organisers wanted to kick us off. We were pulled off the stage in the end by the army and police in the middle of the night. The man who is now the President of Croatia is a composer and musicologist. He was watching the show and recently he described it as the most radical and provocative sonic performance he has ever seen.

The Croatian Communists were very angry after the show, demanding to their fellow communists in Slovenia that somebody had to do something about Laibach, stating that this was simply too much, ‘they (Laibach) have desecrated the holy and stepped over the line’.

1983: XY – UNSOLVED – TV Tednik (TV Weekly) Interview, RTV Ljubljana

The scandal ended up with this interview. This was a plan, a political strategy, ‘how to get rid of Laibach, how to do it elegantly – exposing them publicly on the main TV programme. After they appeared, they will cease to exist, because the angry reaction of the entire nation will force them to withdraw. And yes, we came to the interview dressed in our military uniforms, which on the mainly black and white TV monitors of that time looked – black and white. It was hard to see that these are in fact Yugoslav army uniforms.

We said, ‘Ok let’s do a performance, let’s not move at all in front of the camera. We are just going to give our answers in a kind of political, manifest way’. It was quite shocking to watch that on the TV, although nothing that we said was really problematic, everything was basically a straight manifest and we even quoted Yugoslav politicians in a elegant and positive manner. The interview journalist additionally edited the interview and in the end literary called for a public lynching which was of course soon recognised as an over-the-top abuse of the media. Nevertheless, Laibach was officially forbidden for the next five years.

A huge public debate happened after the transmission of this interview and went on for several months, even years later. Slavoj Žižek himself wrote several articles about it as well. He described the whole thing as over-identification – Laibach actually being more Communist and more ‘stately’ than the state system itself.

1983: The Occupied Europe Tour

It was impossible to get official permission to play in Slovenia, though somehow we managed to do a few shows, either without using our name, just putting a black cross on the poster, people knew this was Laibach. But we said, ‘If we are unwanted here, let’s go and do a tour in Europe.’ This was very difficult at that time, we didn’t know any promoters or concert agents in Europe and nobody knew about us, there was no internet, no nothing, organising a tour was a pure adventure. But we succeeded and went on a tour through eastern and western Europe, doing something like 20 than shows in Poland, Hungary, Austria, Germany, Denmark, Holland, ending it in London with a victoriously chaotic show, which brought us the deal for an album for Cherry Red Records.

Laibach vs. USA

The first time we tried to go to the States was 1987. It was quite a process to get the visa. The form asked if were members of a communist party or some extreme organisations and so on. We said ‘yes’, and declared ourselves as communists although in fact we never were. So we didn’t get permission the first time. Second time around we decided to keep that quiet, and went to US with Michael Clark. It was always fun to get into America, but this first time it was shocking – for us it was a culture shock.

People from Sonic Youth were at the show we had in New York end of 1980. The audience were obviously told we were the scariest band in the world, maybe Nazis. Being in uniforms, coming from Eastern Europe which the Americans didn’t know much about, never mind where Slovenia is or Yugoslavia was, they mixed everything and thought we were Germans or Russians or something like that. Doing songs like ‘One Vision’ had a heavy effect on them. There were all kinds of accusations, it was a mixed reaction, some people even had more… fun?

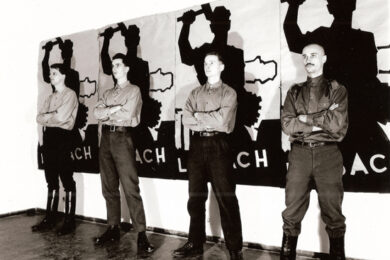

1984: Initiation of the NSK collective

Many people wanted to work with us. Either within the theatre or films or art… Since Laibach was officially forbidden between 1983–1987, this was the perfect situation to establish something that would become bigger than Laibach, and it would practice the same methods in diverse media, only under a different name. So that’s how the NSK was established in 1984. It took Laibach’s motifs and ideas and implanted them in diverse media groups, working within the theatre, art, design, etc.

That really functioned successfully in the ‘80s. We did some great events together, mixing our skills and knowledge. We did a big theatre project called Baptism Under Triglav and some big exhibitions and also this very important poster campaign, which kind of started the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia and produced a huge political scandal.

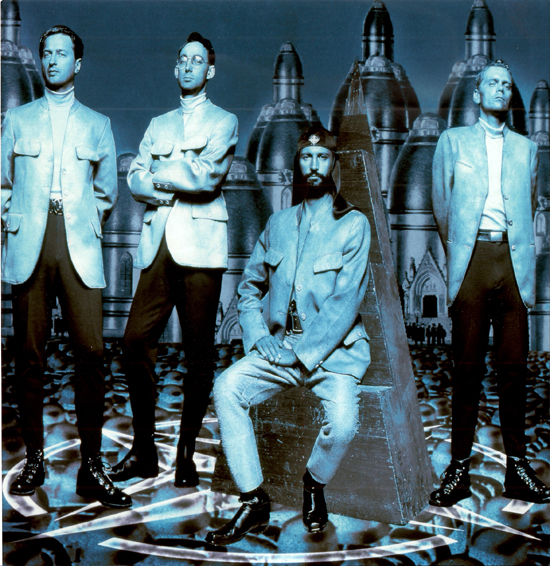

1987: Signing to Mute and the Opus Dei album

We had a very clear strategy in the ‘80s. We knew we had to sign to one of the important independent labels in Britain if we want to do something on a larger scale in Europe and the world.’ Mute was a really the prime target for us and we finally signed in 1986. For our first album on Mute we wanted to do something that was a bit more communicative, not some totally heavy industrial thing. Opus Dei came together successfully, at that time we were also listening – out of curiosity – to Queen and other similar groups, so in a way we let ourselves be partly inspired by European po(m)p. We recorded this album in Slovenia, very fast, something which does not happen nowadays. It was a successful mixture; quite unique at the time and Mute really launched us worldwide with it.

Pop culture was more or less the same everywhere, even in the ‘60s and ‘70s we could get hold of pretty much everything that was important within the music, so we knew quite well what was happening in the UK or Germany or France or in the States. We could listen to a lot of pop music on the regular national radio in Slovenia, so we were definitely influenced by it. Soon we realised that it would make no sense for Laibach to create their own pop songs or even to try to produce pop emotions like everybody else did. Instead we decided to use this subversive method of doing interesting covers. At the time, when people were doing cover versions these usually sounded the same as the original. We always understood that all songs we covered were historic material which we could use innovatively and make something completely new out of them. This was our method.

1987: ‘Life Is Life’ – Laibach and the art of the cover version

Pop culture was pretty much the same everywhere, even in the 60s and 70s we got pretty much everything that was important, what was happening in the UK or Germany or France or in the States. We could listen to music on the regular radio, so we were influenced by Western pop culture. We realised straight away that it would make no sense for Laibach to create their own pop songs and sing in this way that everybody did and produce pop emotions. If we want to be interesting we actually have to use this subversive method of doing interesting covers. At the time, when people were doing cover versions they sounded the same as the original. We started to understand that this is all historic material which we can basically use and make completely new songs. This was our method.

1990: Laibach finally play their hometown of Trbovlje

This concert a very symbolic gesture. Actually it was the first time that we played in Trbovlje, finally, after ten years, in our hometown. And it was a very nice and emotional ceremony, with a miner’s brass band and speeches welcoming us, etc., but the police were still watching around the corner… It was the middle of winter in this old power station and, when we started to play – and we played loud – all the dust was coming down from the factory ceiling, like a black snow. This was a huge industrial space, minus 15 degrees and the band was bare-chested on stage. The audience were drinking hot tea so they didn’t freeze. It was a symbolic event because the same night the Slovenian parliament declared independence; not that the two were heavily connected, but Laibach in a way was a symbol of independence. We did a lot of concerts and a lot of events that were important also in wider, political terms. Not that we are or were a political group, but we were very successful in provoking political reactions, very useful material for a political debates.

2008: LAIBACHKUNSTDERFUGE

We got an invitation from the Bach festival in Leipzig, where Bach lived, worked and died. One part of this traditional festival is dedicated to pop interpretations so they invited us to do our interpretation and we decided to do ‘Kunst Der Fuge’ because it’s the only thing that wasn’t specifically written for any instrument. It was Bach’s meditation on the mathematical structure of music. In a way this was also a manifesto for electronic music, so that’s why we decided to do it with computers and computer programmes.

2010: Laibach Kunst Exhibition, Trbovlje

We invited the ex President Of Slovenia to open our exhibition in Trbovlje in 2010. He was also in power as the head of Slovenian communists at the time when Laibach were forbidden in the ‘80s. The exhibition in 2010 was basically the same exhibition as the forbidden one in the 1980s, except that it was now a very important cultural event, opened by ex president of the State. He is not in power anymore, he is now a pensioner, but he came and gave a brilliant opening speech. He told me later that Slobodan Milošević was calling him in the mid ‘80s because of Laibach and NSK, being very pissed, demanding from him to do something about us and to stop us somehow. This was back in ’87. He also told me that it was a very hot situation, lots of pressure on him, but he didn’t quite know what to do with us. He wasn’t exactly following, listening or understanding Laibach but he understood we were masters of creating problems, and we did some in Milošević’s Serbia as well. Although it was a very tricky situation at the time of the poster affair, he refused to put us in jail, for which we are, of course, deeply grateful…

2012: Tate Modern Retro-Monumental Avant-Garde. Laibach’s struggle continues

We were quite scared that it wasn’t going to work, because the Turbine Hall space is huge and acoustically very difficult. We didn’t have much time for the proper sound and light check, because of all the rules in the Tate Modern – not being able to make noise during the day – so we had to work and prepare everything during the night. We had problems with PA, projections, electricity, with diverse regulations, etc. We really were fighting heavily to make the sound work. During the soundcheck the sound was disastrous. During the concert, due to some miracle, it all worked fine.

It’s much more difficult now than in the ‘80s to do what we do. Back then it was a Dadaist adventure which we took with a lot of humour, but nowadays things within pop culture and cultural politics and the economy are getting extremely difficult. Especially after the breaking down of the Wall, establishment of the internet and with capitalism polluting the area, it’s a state of war. Independent labels practically vanished, record sales are going down, there’s a big battle of survival on the market and it is difficult to do what we do and as we do it. It’s a jungle out there, and we are all fighting for our place. History? Nobody cares. It’s only an ongoing battle of survival of the fittest…

An Introduction To… Laibach / Reproduction Prohibited is out now on Mute. Laibach play the Incubate Festival in Tilburg, the Netherlands, this Sunday September 16th