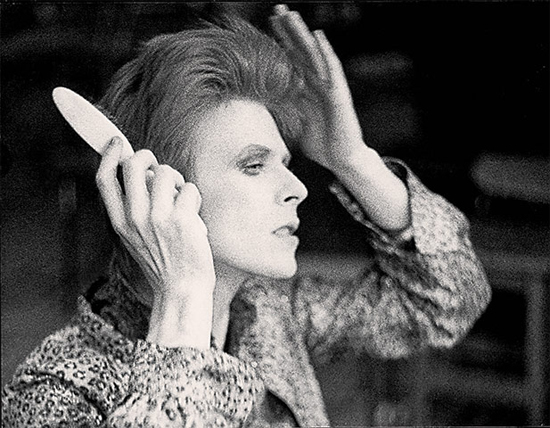

It’s a cold, rainy January evening in 1972. The scene is Heddon Street in London’s West End; just a stone’s throw from Soho’s hotbed of rock ‘n’ sleaze. Outside of the furriers, K. West, a man cuts a dashing figure. He clutches a Gibson Les Paul guitar, clad in a skin tight turquoise jumpsuit. The picture that will eventually immortalize this evening shows the man’s hair as tinted blond. But he will soon be known as the flame-haired Glam rock god, Ziggy Stardust .The man behind this mask, David Bowie, stands on the precipice of stardom & infamy, an imminent icon. He inhabits the world’s picture as a vivid anomaly; a flamboyant thunderbolt through the dreary, denim-clad heart of early 70’s England. The surrounding buildings are remnants of an old world. But high above, the night sky holds infinite possibilities.

Ziggy Stardust was the conduit through which David Bowie finally became a popular figure. Previously he had been considered a one-hit wonder or worse, a "pervert" (according to his then publicist Anya Wilson). ‘Space Oddity’ was a novelty hit in 1969, cashing in on Neil Armstrong’s moon landing. But since the release of ‘Liza Jane’ in 1964 (under the moniker David Jones & The King Bees), Bowie had already spent the best part of a decade trying on a cast of characters with little success. Mod, beatnik vaudevillian, mime artist, post-hippy Dylan folkie, metal-head in drag, a flaxen-haired, one man Brill building with heavy thoughts.

None of these incarnations hit paydirt, but they gave Bowie a Zelig-like perspective on the 60s cultural tangents, from showbiz to the avant-garde. It served as a kind of apprenticeship, every move a stepping stone towards Ziggy. Musicians, publishers and stylists created a micro-world around him that belied the facts and figures. Then-wife Angela was pivotal too, relentlessly promoting her husband & encouraging extreme fashion tendencies. Bowie recruited a band that consisted of musical foil/guitarist Mick Ronson, bass player Trevor Bolder and drummer Mick ‘Woody’ Woodmansey, as well as signing a deal with Elvis’ label RCA in September 1971. With new manager Tony Defries in tow he established the Mainman company. Together they envisioned a demi-monde of superstardom with Bowie at the centre. This owed as much to the factory of Warhol’s DIY celebrities as it did the studio system of old school Hollywood. The pursuit of fame was an obsession.

The aspiring star had visited Warhol’s legendary Factory while on a promotional trip to America & seen Pork, the pop artist’s outrageous stage-show at London’s Roundhouse. Bowie also penned a tribute to Warhol on Hunky Dory, and that album’s cover art was a nod to Greta Garbo (not Veronica Lake or Lauren Bacall, as has been suggested). Visitors to Bowie’s sprawling Haddon Hall hub recall pictures of other Hollywood legends strewn across the Beckenham house. Warhol’s dictum that in order to be a star you must live like one became a vital cog of the Mainman machinery, eventually to the point of financial disarray.

Stardom was slow to arrive but inevitable. "I am going to be huge, and in a way it’s quite frightening because when I come down it’s going to be with a big bump," Bowie mused at the time, displaying both self-belief and a rare lack of foresight. Once success arrived, it would be as enduring as it was monumental. Ziggy Stardust was, amongst many things, a true child of Warhol. It was a meta-narrative about stardom that finally made Bowie into a star.

Ziggy’s red leather boots stepped into a world that was perilously fragmented and ready to embrace the individual. "The centre was not holding," wrote Joan Didion, quoting Yeats, when surveying the late 60s lack of consensus or a coherent narrative thread. The early 70s continued this fall-out. The Beatles, once the robust totem of unity, had split. Rock’s casualties were piling high. Not just the fatalities of Hendrix, Joplin, Jim Morrison & Brian Jones. Visionaries such as Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett and Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green had suffered Icarus meltdowns.

A generation’s greatest minds were left singed or burnt out entirely, often frazzled by the perceptual Pandora’s box opened by LSD. Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe, two silver screen icons referenced either directly or indirectly by Bowie during the Ziggy period died tragically in the previous decade too. In America, disunity over the Vietnam War continued. Protesting students were killed at Kent State University and the civil rights movement lost some of its most potent forces, including Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. The hippy dream had turned into an atomized nightmare, the counterculture splintered into factions, some of them violent. In England, the conflict with Ireland raged on, punctuated by outbreaks of attacks from the IRA.

It’s not too much of an interpretive leap to see how this maelstrom informed the concept Bowie sketched of Ziggy on The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust. A messianic rock star spreads extraterrestrial messages, for which he is a cipher, across a world on the brink of apocalypse. His message of redemption is soaked up by an adoring audience but in the process he is sapped of his life force. It is essentially a sci-fi mythologizing of the previous decade’s aftershocks. Like most rock concepts, Ziggy’s doesn’t withstand close textual analysis, being more of a universe the songs inhabit and only occasionally refer to.

Science fiction as a genre was particularly resonant in an age of moon landings. The singer spent many a late 60s evening contemplating the existence of UFOs with friends like George Underwood. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001:A Space Odyssey (1969), a film that chimed with the space travel zeitgeist, informed Space Oddity. Hunky Dory‘s ‘Oh! You Pretty Things!’ had quoted Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race (1871), widely regarded as the first sci-fi novel. Even more vital to the formation of Ziggy, however, was another Kubrick film, the controversial A Clockwork Orange (1971). Not only does ‘Suffragette City’ reference the ‘droogs’ but the Spiders’ sartorial aesthetic was a dandified twist on the uniforms of Alex’s mob, right down to the diamond-encrusted crotch of Bowie’s jumpsuit. Dystopian ultra-violence fused with post-Warhol ultra-glamour.

An idea like Ziggy had been fermenting in Bowie’s imagination for some time. In 1968, he sketched ideas for an unrealized rock opera Ernie Johnson, about a self-destructive figure who shops at Carnaby Street; rock & roll suicide meets The Kinks’ dedicated follower of fashion. ‘Cygnet Committee’, on his eponymous 1969 album, is ostensibly a lumbering trawl through the detritus of the counter-culture. It was prompted by Bowie’s disillusionment with Beckenham Arts Lab; the broken hippy dream writ small .But the song’s central character, a Christ-like martyr, is a dry run for Ziggy’s ‘leper messiah’.

The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust was both a chameleonic shift for Bowie and a cumulative work. It distils the sensory overload of the 60s and Bowie’s own past into one lean, mean Xerox machine. But Bowie bottles it with the singular vision of an auteur, deftly managing to shape the future in the process. Ziggy arose from a time when discourses on rock stardom were proliferating. Indeed, the father of rock criticism and the genesis of Saturday Night Fever, Nik Cohn, published a novel in 1967, revising it in 1970, called I Am (Still) The Greatest! Says Johnny Angelo. The book’s titular hero is Ziggy’s foreshadow; a mythical martyr whose pansexual, all-encompassing appeal emphasized how the rock star had become the secular deity of the twentieth century.

Incidentally, Cohn wrote the text to Guy Peellaert’s (future Diamond Dogs painter) Rock Dreams; iconoclastic tableaus of rock’s pantheon that not only featured Ziggy but rendered overt many of the taboos Bowie was bringing to the fore too.

When ‘Starman’ appeared in April ’72, it was seemingly out of nowhere. It was widely believed that this was actually a follow-up to the similarly-themed ‘Space Oddity’. There were bigger singles throughout the summer. Indeed, there were bigger glam rock singles, chiefly T.Rex’s ‘Metal Guru’ and Alice Cooper’s ‘School’s Out’. But Bowie’s impact was, like any icon’s, transcendental. The June Top Of The Pops appearance remains one of pop’s eureka moments. As Bowie drapes his arm suggestively around Ronson’s shoulders, a surge of electricity went up and down a nation’s spine. Homosexuality had been legal just five years.

It was a particularly shrewd master-stroke in an era where 91% of families now owned a television. ‘Starman”s morse code signal, actually the sound of a guitar and piano mixed through a Countryman phaser, telegraphed terrestrial aliens everywhere. Little matter that it aped the febrile rush of The Supremes’ ‘You Keep Me Hanging On’; kids sat in living rooms lost in Bowie’s carefully constructed reverie as their dads fulminated. Maybe they nervously changed channels. Like all great pop, this was not something to be shared with the older generation. If the small amount of people that actually bought the Velvets debut all formed bands, this appearance had an equally galvanic effect.

Hastily concocted at the behest of RCA’s A&R executive, Dennis Katz, who believed the album lacked a single, ‘Starman’ was a typical example of pop’s calculated enchantment. Opening in a narcotic 12-string haze, the song is quickly whipped into shape by Woodmansey’s drum fills and the pied piper magnetism of Bowie’s story-telling. By the chorus, a shameless lift of Judy Garland’s ‘Somewhere Over The Rainbow’, Ziggy/Bowie had arrived in style. The song’s deceptively simple charms were an ideal curtain raiser to Ziggy; part seer, part charlatan. Its inclusion also raised the quality of the album. It relegated an energized but unremarkable version of Chuck Berry’s ‘Around & Around’ ,renamed ‘Round & ‘Round’, to future b-side status (it was the flip to ’73’s ‘Drive-In Saturday’).

The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders From Mars followed on June 6th, rising to five in the charts, where it spent 105 weeks. All his output since 1969’s eponymous album re-entered the charts, most successfully Hunky Dory, which climbed to three. A star was born and with it a new era. For Ziggy represented a new level in glitter rock: high glam. Bowie’s ally and adversary, Marc Bolan, front-man of T.Rex, was already a sensation, enjoying hits such as ‘Hot Love’ and ‘Get It On’. Bolan had spent the last decade pursuing stardom in avenues remarkably similar to those Bowie was travelling down.

Now Bolan was the elfin king of glam. He slapped glitter on his face and offered rock & roll with pop hooks and pouty poise. Bolan was a glimmer of hope in a musical landscape that had begun to take itself too seriously.

Post-Pepper, the climate was weighed down by the osmium portents of heavy and progressive rock or the sophisticated solipsism of the Laurel Canyon singer-songwriters. Bolan was hangover hippy fey but his transparent pursuit of stardom was a throwback to pre-counterculture values. Like so much of early 70s pop, there was something revivalist about T.Rex’s appeal; a vision of satin and velvet but lacquered in the slap-back echo of Sun Studio.

Bolan got there first but Bowie had been toying with similar ideas to his sparring partner. In the late 60s he studied with mime artist Lindsay Kemp, a denizen of the neon-lit Soho world so close to where the Ziggy cover was shot. He appeared as Cloud in Kemp’s production Pierrot In Turquoise, welding music and movement together in a manner that would be germane to later developments. He had briefly played with an ensemble called The Riot Squad, the players draped in garish clothes and bright make-up, a tantalizing glimpse of what was to come. Such pantomime urges proved irrepressible, and in 1970 he performed with a band, The Hype, that included new sidekick Mick Ronson as well as bassist Tony Visconti, the producer he shared with Bolan. The band adopted pseudonyms and adorned themselves in comic book hero costumes, a swishy contrivance for which they were heckled at venues like the Roundhouse. Visconti claims these performances are the true birthplace of glam, not least because photos reveal Marc Bolan mentally taking notes in the audience.

Like Bolan, Bowie’s Ziggy was something borrowed, old and new. Bowie also injected a theatrical wink and wiggle into an increasingly staid musical landscape. However, his dabblings were darker and more diverse. With Ziggy he forged a vari-coloured hybrid, sculpted from sources high and low ("Nijinsky meets Woolworths"), English and American, rock and non-rock. Ziggy’s glitter rock tendrils extended their reach across a fractured post-Beatles music scene. It cast a net over the hordes of singles fans and the more cerebral album markets; a nexus figure for a pluralized musical climate. The concept was deeply serious and playfully camp; the product of a man adopting masks not just as a showbiz facade but working through a family history of mental illness. Terry, his half-brother, had shaped many of his musical tastes, and had been diagnosed as schizophrenic.

A voracious reader, Bowie’s preoccupation with Nietzschean supermen and Aleister Crowley’s ‘magick’ had informed The Man Who Sold The World and Hunky Dory. On both there’s a sense of characters gripped by the terror of the sublime, in power, madness or death. Both "frightened by the total goal", as on Hunky Dory‘s ‘Quicksand’, but doggedly in pursuit of it. Here was a man with grand ambitions but standing on the verge of a psychic abyss. In Ziggy Stardust& the other alter-egos Bowie constructed in the 70s, he found a safe playground to indulge all his anxieties and those of the world around him. "The only way to exorcise pain is to turn it into a theatrical experience," the singer noted.

Being a beat and jazz aficionado as well as a Little Richard/Gene Vincent enthusiast, Bowie was as much under the spell of Americana as he was Anthony Newley and Syd Barrett. Barrett impressed him not only for his ability to "decorate a stage" (and his face) but because the Pink Floyd singer sang in his native tongue (his favourite Floyd song was Arnold Layne, a cross-dressing vignette). Stateside, the work of The Stooges and the Warhol-sponsored Velvet Underground exerted a powerful influence over him; street level poetry and guttersnipe garage. From the former, he would take leader Iggy’s namesake, adding a ‘Z’, and the singer’s hell-raising stage antics. Iggy had covered himself in gold in performance; ground-zero glam. The Velvets introduced a taboo-busting lyrical perspective into the rock lexicon, while possessing a candy pop sensibility amid the avant-garde discord.

Ziggy was, after Sgt. Pepper a new chapter in post-modern pop. Like Pepper, this was rock ‘dressed up’ in outfits or as a ‘pierrot’, to quote Bowie. A cosmic conundrum then: a unifying figure for the rubble of the late 20th century. Ziggy was a compendium of Bowie’s myriad obsessions up to that point. Bowie smoothes down the rough edges of the US east coast trash aesthetic, fashioning a gleaming front for the proto-punk subversion. He sings in avowedly English tones, owing as much to the Small Faces’ Steve Marriot of ‘Lazy Sunday’ as he does Newley.

But Ziggy’s peacock strut is also the powerhouse bravura of American rock & roll, equal parts Little Richard and Iggy Pop. The album’s vernacular is Anglo-American: "Chevys and milk floats" co-exist in the same song. Even contemporaries T.Rex get gobbled up in Bowie’s ‘Get It On!’ exclamations on ‘Star’, then get name-checked on both ‘Starman’ and the number 1 hit he penned for Mott The Hoople, ‘All The Young Dudes’. He also would sing ‘Lady Stardust’ on stage to a backdrop of Bolan; part eulogy, part assimilation. "Never wear a new pair of shoes in front of David Bowie," warned Mick Jagger.

When talking of Ziggy in recent times, Bowie has emphasized more esoteric names. American psychobilly oddity, ‘The Legendary Stardust Cowboy’ had part of his name pilfered while the figure’s sad fate as a joke that wanted to be taken seriously added more poignancy to the Ziggy identity. In this regard, Vince Taylor was even more illuminating. Taylor was an English rocker who faked being an American and enjoyed some success in France. Best known now for his 1957 ‘Brand New Cadillac’, which The Clash covered on London’s Calling, Taylor actually met Bowie in London during 1966. An excerpt from Bowie’s abortive autobiography reports a bizarre encounter which involved Taylor locating spacecraft destinations on a map. He provided Bowie with yet another cautionary tale on the perils of the rock star, devoured not only by demands of the machine and audiences but their own toxic egos.

Renowned for taking to the stage in white robes, believing himself to be a sacred messenger, he was Ziggy’s "leper messiah" incarnate. Equal parts rock & roll Mercury & delusional psychotic, Taylor was duly woven into Ziggy’s tapestry of the populist and the marginal.

Consequently, it wasn’t just the obvious alien trope of Ziggy that made it appealing to the outsider. The genealogy of Ziggy absorbs the highs and lows, not just of culture but the rock dream. Not only did Bowie reference the successes, The Beatles, The Stones, T. Rex, but he wove the disenfranchised rejects into the Ziggy fabric; degenerate American garage, the casualties, the avant-garde. Bowie of course, would dominate the decade, with what Ian McDonald referred to as his "sensitivity to cultural context." On another level his championing of the underdog (cynics would call it exploitation) would create a new kind of pop star, one who made a very direct communications to the disaffected, those in "darkness and disgrace."

Being a creature of supreme equipoise, Ziggy combines Mick Ronson’s Jeff Beck-inspired, Marshall-amplified riffage of The Man Who Sold The World with the mellifluous, finely crafted melodies of Hunky Dory. On Hunky Dory, Bowie had placed exacting standards on himself as a writer, composing predominantly on piano with an old school, Tin Pan Alley dedication. Several songs, including ‘Lady Stardust’ & ‘Bowie’s reading of Ron Davies spiritual ‘It Ain’t Easy’, held over from those sessions, emerged on Ziggy. Embryonic versions of ‘Hang On To Yourself’ and ‘Moonage Daydream’ date from an even earlier period, having been already released by Arnold Corns, an ill-fated rock band conceived by Bowie and ‘fronted’ by Ziggy costume designer, Freddy Buretti.

‘Five Years’ begins Plastic Ono sparse, dominated by Woodmansey’s anaesthetized drum pattern & Ronson’s spare piano chords. Bowie’s doomed oracle is a patchwork of influences; the sad-eyed reportage of The Beatles’ ‘A Day In The Life’ & the build of Lennon’s solo ‘Mother’, the icy detachment of Lou Reed’s observations & the saturnine panorama of John Rechy’s City Of Night. Rechy’s landmark gay novel, published in 1963, permeates ‘Five Years’, right down to the jaded mention of the ‘queer’. Bowie’s tone of world-weary cynicism and a child-like sense of wonder would recur on later Marvel comic journalism like Panic In Detroit. Here the images are novelistic in their sharp, poetic economy, particularly the oblivious character in the ice cream parlour. By the end, a broken carousel of orchestration flickers through the track, a distant echo of Pepper’s bandstand bonhomie and a fractured world. Bowie’s voice reaches a lacerating intensity (apparently real tears were shed on the Trident studio floor).

Part of Ziggy‘s enduring appeal lies in the filigree of its finer details, a virtue which the forensic clarity of countless remasters has only illuminated. On ‘Soul Love’, Bowie’s breathy alto sax flutters through the stereo image with the rude sensuality of an outlaw overdub. Similarly, the background voices on ‘Suffragette City’, alternate between the left and right speaker with dizzying vitality.

Producer Ken Scott’s lightness of touch at the mixing desk is what really elevates Ziggy. An engineer for The Beatles, Scott posits Bowie’s music in pared-down yet striking settings. His treble-heavy production may be a reactive wisp to the syrupy density of late 60’s rock, but there’s mutton-chopped muscularity here too, largely due to the backing band. ‘Suffragette City’ is White Light/White Heat buffed to a lustrous sheen and it surges along frantically, spurred on by an ARP synth-administered bank of artificial saxes. Throughout Ziggy, Ronson’s arrangements match Bowie’s songs, imbuing them with this sort of fine detail. The dynamic interplay between acoustic/electric is also a salient feature of the record, perhaps best heard on ‘Ziggy Stardust’s effortless switching of gears from elegiac to sabre-toothed snarl.

As with ‘Starman’, closer ‘Rock n’ Roll Suicide’ revisits the sentimental bombast of Judy Garland. ‘Rock n’ Roll Suicide’ also owes something to the adolescent operettas of Cilla Black too; chocolate-box orchestrations with a surprisingly hard centre. When it swells to its show-stopping crescendo, the ersatz and the deeply poignant become inextricably linked. Emotion is the ghost in this star machine. Safely shrouded in an aesthete’s hauteur & the allusions of a culture vulture, it would be easy to dismiss Ziggy (and in turn Bowie) as a "chicken hearted straw man" as US rock critic Lester Bangs did. But it seems like a cosmetic response to just the cosmetic layer in Bowie’s "glass onion."

Much of Ziggy’s impact was due to Bowie’s provocative use of androgyny and bisexuality as viable marketing tools for a rock star. On The Man Who Sold the World‘s cover he reclines on a chaise longue wearing what he assured people was a "man’s dress". Inside the record, ‘Width Of A Circle’ rapturously speaks of a tryst with an almighty force; man sex as the mingling of simultaneously infernal and mythical energies. Again, Bowie was tapping into a lineage that was already there, albeit in a rather clandestine vein. There was the casting couch of manager Larry Parnes, whose roster of teeny bop UK talent included Billy Fury (who sang Bowie’s ‘Silly Boy Blue’) as well as Marty Wilde, Johnny Gentle and Georgie Fame, all names that sound like future food for glam rock stew. Parnes was parodied in 1958 by Peters Sellers with a roll-call of names that sound like Ziggy rejects (Matt Lust! Clint Thigh!).

There had been nudges and winks over John Lennon’s relationship with Brian Epstein, whose management of The Beatles was perhaps the most famous example of a gay man’s shrewd, bespoke vision pulling the strings behind pop stardom. But there was also Kit Lambert (The Who) and Simon Napier Bell (The Yardbirds, Marc Bolan). Earlier in his career, Bowie had his own gay manager, Ken Pitt, a mentor to the singer whose unwavering faith in him had proved integral to his evolution. Indeed, it was Pitt who had brought Bowie an acetate of the Velvets’ epochal debut album back from the States. Tastemakers, deal-makers sealed with an outlaw status, gay men had an unusually symbiotic, rich relationship with rock & roll back then. Not only were they able to market bands successfully, they proved to be almost talismanic to a certain sector of post-war male society looking for a new approach from previous generations. As The Who’s Pete Townsend told Jon Savage recently in Mojo, everything was up for grabs.

Not to be outdone in the outrage stakes, The Stones courted controversy by dragging it up for the sleeve of ‘Have You Seen Your Mother…?’ But they were reassuringly heterosexual (their unreleased ‘Cocksucker Blues’ stayed in the closet). Bolan had frankly admitted to not being repelled by the notion of being with another man. But where Bolan was cuddly, Bowie was spiky, a little confrontational. He was also, of course, a married man with a child but his "I’m gay" admission to writer Michael Watts in Melody Maker, when unveiling the Ziggy guise, was a revelation. It forever let rock’s best kept secret out of the bag.

This has become the subject of much debate subsequently. It’s all often dismissed as a calculated final flourish to Ziggy’s media savvy iconography: another layer to the character’s studied artifice. Tellingly, however, in the Watts interview Bowie claims it was ever thus, even when he was David Jones. In interviews as late as 1979 Bowie was still claiming to be bisexual, although by then he was understandably wearying of the question.

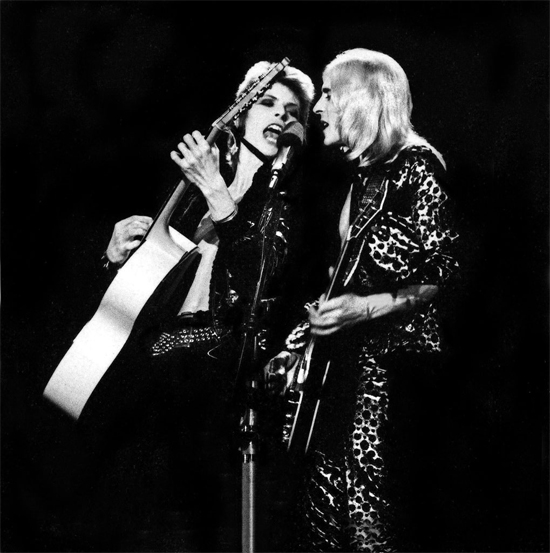

Ziggy is replete with allusions to homosexuality and blurring gender boundaries. ‘Lady Stardust”s homage flits between he and she while the lyric’s "love I could not obey" echoes Lord Alfred Douglas’ "love that dare not speak its name." Similarly, lines like "oh how I lied when I asked if I knew his name" sound like a closeted lament when faced with ‘straight’ society. There are innuendoes galore on songs like ‘Moonage Daydream’ both figurative and syntactical ("put your ray-gun to my head, the church of man, love!"). There’s also the controlled hysteria of the "oh hit me!", resounding through ‘Suffragette City’s mix like a gay liberation rallying cry. An infamous part of Ziggy’s stage repertoire was Bowie’s ‘fellating’ of Ronson’s guitar; a boon for photographers and an audacious new argot for mainstream rock’s vocabulary. Rod Stewart camping it up while singing a folk-hero elegy for a deceased gay friend on ‘The Killing Of Sister Georgie’ seems implausible without Bowie’s trailblazing.

The tremors were immediate. Jobriath was marketed as Bowie’s, or rather Ziggy’s, US analogue, albeit to little success, due in part to the country’s more conservative market and the overcooked extravagances of his material. Other ‘Bowie’ boys would fare better. Freddie Mercury had taken note of Bowie while the Queen singer was working with Beatstalker/future Only One Alan Mair in Kensington Market. He referred to Bowie as ‘the ultimate’ pop star, an uncannily sharp observation as he was still in his pre-Ziggy doldrums.

Mercury and Taylor attended Bowie gigs, and part of Queen’s flamboyance has to be ascribed to his influence. The gender-bending of early 80s pop is almost singularly indebted to Bowie – performers from Boy George to Marc Almond picked up a baton that Ziggy had originally carried, however cynically. But the epicene Ziggy went further, allowing male and female performers to breathe in a less rigidly gendered universe, from Japan to Prince, Annie Lennox to Madonna. Ziggy brought rock’s Kinsey scale to the masses. The actualities of Bowie’s biography are perhaps irrelevant. Ziggy’s cultural sexual orientation changed the pop world forever.

Bowie’s bisexual persona, whether it be cultural construction or biographical reality, has been analyzed by two polarised camps. The gay press who largely wanted to hold him aloft as a "gay Elvis" (Boy George), and felt betrayed when he rejected the mantle. Or a largely heterocentric male music journalist perspective who were dismissive that it was anything other than media-manipulation. Rock music is, more than any other medium, a tribal concern, and the Charles Shaar Murrays et al may have simply been more comfortable with dismissing the notion that their hero was anything other than a hetero dude playing panto with sexuality.

A post-Aids glaze on a pre-Aids phenomenon: it is perhaps indicative of a more sexually rigid culture that Bowie, a married man with a child, outing himself was deemed credible in 1972 and yet Brett Anderson’s actually more transparent remarks ("I’m a bisexual man who’s never had a homosexual experience") were endlessly lampooned 20 years later.

Of course Bowie’s own inconsistency with the matter hardly helps. But Aids enforced an aggressive emphasis on conventional sexual classifications on a society that seemed to be moving towards eroding them. Beyond Ziggy, there was the throwing all cards in the air sexuality of Pacino in Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon, a peculiarly 70’s kind of iconoclasm that would today be unmarketable.

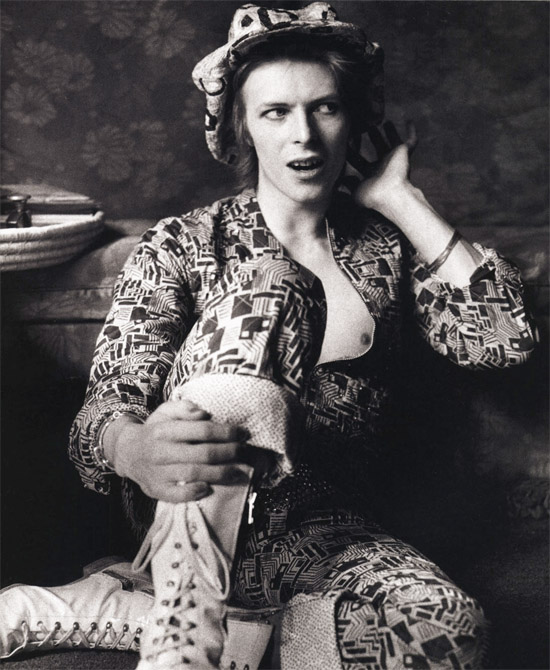

After the release of the album, Bowie’s star rose inexorably (he was 1973’s biggest selling male artist). As Glam generally became bequeathed in increasingly dull fabrics, Ziggy went down a rabbit hole and things got more and more curious. The image grew more extreme, accentuating the kabuki theatre aspects of this ‘cat from Japan’, courtesy of the designs of Kansai Yamamoto. The androgynous dimension to this fusion of music, movement and theatre where males play the roles of both sexes clearly appealed, as did the dramatic colour schemes. Initial gigs for Ziggy took place at such glamorous epicentres as The Toby Jug in Tolworth & The Friars in Aylesbury. Pretty soon the show was upgraded to the plush environs of The Rainbow, where with former cohort Lindsay Kemp Bowie staged a new benchmark for rock theatre.

Concomitantly, the music was becoming drawn from a more vivid palette. It was also splintering; as if Ziggy’s post-modern patchwork was coming apart at the seams. Where Ziggy was tasteful light and shade, 1973’s Aladdin Sane was tense tenebrism. Ronson’s roughhouse riffs, Mike Garson’s Dali-spiked, ivory tinkling and Bowie’s surreal full-on plunge into America all amounted to a more genuinely decadent beast than Ziggy. Roxy Music, whose retro-futurist collage, courtesy of the manipulations of Eno’s VCS3 synthesizer, was a startlingly modern proposition that in comparison made Ziggy look quaint. The Martian doo-wop of 1973’s ‘Drive-In Saturday’ represents an immediate sea change in Bowie’s work, years before he worked with Roxy’s untutored innovator.

Post-release, a gruelling world tour beckoned. It set Bowie on a treadmill that drove him to the point of nervous exhaustion. Meanwhile, the Mainman hype machine went into overdrive, although its profligacy never extended to paying The Spiders decent wages. Defries had orchestrated the Ziggy phenomena with requisite chutzpah but now Bowie was deprived of the guiding hand of a mentor like Pitt. A gulf opened up between Bowie and Defries, principally due to royalties, just as the singer became increasingly estranged from his wife, Angie. Meanwhile, his ambition and cultural appetite span into different orbits: even closer towards America, Soul, Burroughs and the never realized prospect of musicals. As tight a unit as the Spiders were, they became an albatross. Woodmansey’s conversion to Scientology and an obdurate unwillingness to lay down a Bo Diddley beat on ‘Panic In Detroit’ didn’t help much either.

Realizing that Ziggy’s "fag rock" (US journalists words) would never make him anything other than a bi-coastal cult figure in the States and sensing the alter ego’s make-up was sinking into his skin, Bowie retired Ziggy on July 3rd 1973 at Hammersmith Odeon. Then he bid farewell to the remaining Spiders (the drummer had already departed) on Pin-Ups (1973).

However, Ziggy was a harder costume to hang up perhaps than David envisaged, and 1974’s Diamond Dogs is the character’s real final encore. An ever increasing obsession with the Stones (& cocaine) thrillingly converged with his aborted stage production of ‘1984’ and Burroughsian cut-ups: Brown Sugar at the Grand Guignol. Bowie relentlessly moved forwards, finally exorcising Ziggy with the ‘plastic soul’ of Young Americans (1975), which spawned a US number one with ‘Fame’. After that Bowie hurtles along with such restive creative spirit that each album seems to be made on a cusp, looking forward to the next horizon. The Gnostic white lines/white funk of 76’s Station To Station and the pioneering Berlin albums all chart a period that has grown in critical stock exponentially over the years.

Consequently, Ziggy gets a little overshadowed. But it remains glam rock’s most cohesive statement, even if Aladdin Sane has emerged as the Ziggy era’s crowning achievement. Now, pop is forever languishing in excessive quotation marks and knowing appropriations of kitsch & camp. Irony and allusion seem like overworked pantomime dames. But back then Bowie and Roxy’s distancing strategies and shiny projections all seemed fresh, bold and alien.

Ziggy’s shadow has cast itself long and large. Who was Johnny Rotten if not Ziggy’s Quasimodo younger sibling, wrestling the Stooges and the Velvets back from his elder brother’s cosmetic gloss? Who, in Bowie’s own words, introduced a "whole theatre of pretension", teaching the new romantics (and virtually everyone since) how to pose. Who expanded rock parameters way beyond their previous limits, incorporating theatre, mime, cabaret and other non-rock devices? Into the early 90s, it was inspiring artists as disparate as Suede and Grant Lee Buffalo. Lady Gaga’s persona is essentially Ziggy redux for a culture that fulfils Warhol’s prophecy on celebrity. Forty years later, Ziggy Stardust is still pop’s greatest piece of theatre, as conversant in modern performance art, old school show-business and the visceral "Wham Bam Thank You Ma’am!" thrills of rock & roll. Like it says on the sleeve: ‘To Be Played At Maximum Volume.’