This article was originally published in 2011 to mark the album’s 20th anniversary

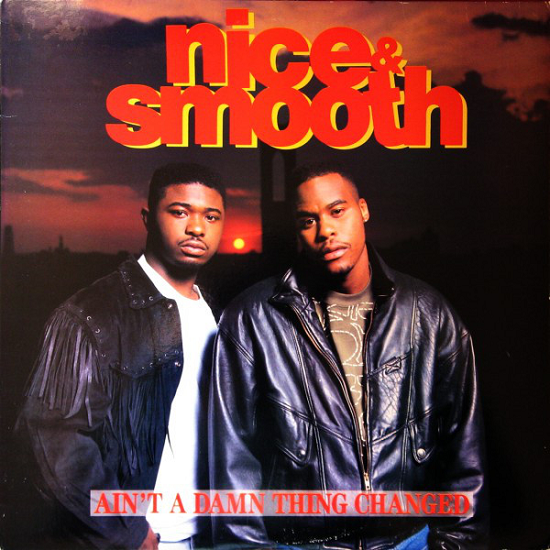

Two grim-faced men stare out of the urban gloom. In the background, the sun is setting. The sky is cloudy, dark, full of portent. Their jackets are black, their demeanour impenetrable. The album title is typed below this portrait in blood red: Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed. It’s 1991, and this is a hip hop LP – so clearly the record found inside this sleeve will be filled with dynamic and bone-chilling reportage from inner-city hellholes, angry tracts detailing racism and reaction from a duo raging as the American dream dies as inevitably and totally as that sun dips below the horizon. Right?

Not quite. While the studied moodiness of the sleeve portrait suggested a radical break from the vivid greens, yellows and blues of their self-titled 1989 debut, the damn things that hadn’t changed by the time Gregg Nice and Smooth Bee released this follow-up were the duo’s inveterate sense of fun, and their enduring belief in the power of hip hop as a party music. ‘Ain’t a Damn Thing Changed’ isn’t a record that many people seem to remember these days, and it wasn’t an easy album to track down in the UK when it was new. Despite being released by Def Jam (or, at least, the subsidiary-umbrella Rush Associated Labels), and containing a string of all-time hip hop party classics, the record wasn’t pressed or released in Britain. Perhaps Nice & Smooth’s faces didn’t fit; perhaps the lack of the kind of social critiques that were making hip hop a music that was attracting rock and indie fans made it a hard sell; perhaps a record of such exuberant, carefree, occasionally smutty humour was ahead of its time. None of which stops the record from being a delight to this day, albeit an often absurd one.

Trying to describe the sonic approach here is tricky: it’s simple enough to outline what retrospectively appears to have been the ethos, but when you start to put it into words it doesn’t seem to make a great deal of sense. ‘Harmonize’, the album opener, might help – it’s a rap song with harmony vocals on its chorus. The existence of Rappin’ Is Fundamental notwithstanding, this was still pretty outre stuff. Twenty years on, it’s at least partially clear where Nice & Smooth were coming from: they wanted to take the same grit-in-the-groove sample aesthetic that informed the classic New York hip hop of the age they were a part of, but adding catchy sung hooks when the mood took them, and in the process re-establishing the genre as the party soundtrack the pioneers of rap’s early years had always felt it to be. They did everything with clearly recognisable style – Gregg the more conventional rapper but beloved of a bouncing kind of a flow that resolved itself into simple but addictive and intrinsically good-humoured sonic patterns, while Bee had a sing-song lilt and a honeyed delivery that comes across as precursor to both Humpty Hump and Snoop Dogg. Like all the great hip hop duos they were a self-contained unit, not just fronting the project but writing and producing everything themselves too. Together they made music that helped create the space in which, first, Mary J Blige and Jodeci merged hip hop with soul, and later, rappers of the 21st century could routinely integrate singing and synths without people accusing them of selling out. You get the feeling they knew it, too – buried there in the thankyous is one to Puff Daddy, which simply says, "You will excel". At that stage Combs’ discography began and ended with exec-producer credits on a Father MC album; in ’92 he would make ‘What’s The 411?’ with Mary and go on to spend the rest of the ’90s changing the histories of both pop and rap.

So in a way it’s easy to see why you’d have wondered how the hell you could promote this record if you were sat in the marketing department of Sony’s London offices when it arrived from New York in ’91. You’ve spent four years getting the rock media to take to Public Enemy, and the other rappers that are getting press and props are angry, militant and politically outspoken. You may well have already heard a new band you’ve just signed out of LA called Cypress Hill, who you’re not sure about either (their 1991 debut never got a UK release, but ‘Insane In The Brain’ would make them bona fide pop stars two years later), so the idea of trying to get radio, TV and press – never mind retail – to buy into a rap record full of strange samples, often unmitigatedly and unapologetically awful singing, and devoid of any kind of obviously serious content probably didn’t come close to computing. But from 20 years’ distance, Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed looks and sounds ever more like one that got away. In a world where De La Soul had shown that hip hop didn’t have to be all scowls and machismo, a record of such richly melodic musical patchworks that was still "hard", courtesy of some of the best use of sampled drums on any hip hop album of the period, ought to have been possible for someone to sell.

The obvious place to have started would have been what turned out to be the second US single, ‘Sometimes I Rhyme Slow’. A deceptively – even outrageously – simple idea, it would have bridged the gap between the PE and De La crowds admirably. All it is, in essence, is the acoustic guitar intro to Tracy Chapman’s ‘Fast Car’, with some drums over the top, and a verse apiece from the two emcees. It’s the one moment on the record where there’s a sense of this as social commentary: not in Nice’s typically free-associative opening stanza, but in Bee’s second, ostensibly the tale of being in love with a coke addict. It’s so out of character you’re never too sure how real it is – can he mean it? Is it all an elaborate set-up for the self-deprecating punchline (he takes her back after 18 months in rehab, "And whaddaya know? She’s sniffin’ again")? – but there is detail in the writing that, allied with the innate melancholia of the Chapman sample, makes it feel like it comes from somewhere that’s recalled rather than studied. On novelty factor alone you’d have surely got some radio play; with a fair wind after that, it could easily have been a hit.

You could then have gone with the first US single, the peerless, mighty ‘How To Flow’ – largely ruined by a needless remix which, with the definitive album version all but absent from online players (indeed, the whole LP isn’t even for sale on iTunes at the time of writing) the modern reader unwilling to fork out for a secondhand copy on eBay will have to make do with. The strangest thing about this song – the one that still confounds anyone who thinks they understand the interplay of creative dynamics that had everyone who was anyone in New York rap competing subtly or overtly to out-do one another from ’86 to ’92 – is realising that it is basically an elaborate homage to the Ultramagnetic MCs. Kool Keith and co may be the key to unlocking the mysteries of the east coast’s golden age – De La were fans, so were the Bomb Squad – but the idea that they’d be the prime sonic influence on what is clearly, on many levels, a pop record seems ridiculous. Yet the evidence is all there in the grooves of this addictively daft song. The drums are the same Dee Felice Trio ones infamously looped by the late Paul C for Ultra’s seismic ‘Give The Drummer Some’ (the source confounded sample-hunters for years, until it was discovered that Paul C had panned the Dee Felice intro and used only one half of the stereo: it’s a fair bet that the record sampled on ‘How to Flow’ is actually ‘Give the Drummer Some’, rather than ‘There Was a Time’, and either way it’s been slowed down considerably), giving the track that sleazy underground rawness, while the chorus is peppered with piano from Joe Cocker’s ‘Woman to Woman’ – or, again, perhaps from Ultra’s ‘Funky’, the first record to sample it.

Yet while the music (apparently effortlessly) managed to merge melodic pop with none-more-hardcore rap, the lyrics are what made ‘How to Flow’ such a gem. The trick Nice & Smooth pull off more or less everywhere on this album is to make raps that sound dextrous and clever enough to impress friends, fans and putative rivals while at the same time so obviously having a ball with it. It’s as if, by freeing themselves from having to Say Something, they realised it didn’t much matter if they made coherent sense or not. This results in lyrics that have the playful abandon and innate charm of an overenthusiastic puppy, and supply similar rewards. It happens throughout the record, but it’s ‘How to Flow’ where Gregg says he’s "got more rhymes than The Mighty Thor", which ranks as one of hip hop’s greatest all-time brags, before managing the considerable feat of constructing a verse that allows him to rhyme "strudel" "noodle" and "French poodle". It is a work of perverse, counterintuitive, nonsensical genius. And while the delivery and sound is important, the key is in the writing: both of them arrive at these ridiculous words to complete the rhyme, but both point out and have fun with the contortions they have to go through to get there. You can see the rhyming word coming, as inevitably and unstoppably as the light at the end of the tunnel that turns out to be another train hurtling towards you, but it’s not just the punchlines that amuse, it’s the set-ups. Throughout the album both write lyrics that don’t just read like they’re funny, they’re funny structurally – it’s the rap equivalent of a limerick: a verse form you instinctively find amusing because of the shape of the package the words are delivered in.

If they’d stopped there, at only two noteworthy songs, the record’s lost-without-trace status would be easier to accept. But of the album’s 11 proper tracks (‘Billy Gene’ is a skit), only a couple are merely OK, while at least six, and possibly seven, are single-worthy examples of the same instinctive blend of street anthem and pop suss. ‘Down the Line’, which features Guru rhyming for the second time in his career over Charlie Parker’s ‘A Night in Tunisia’, ought to be required listening for any true-school devotee (it is every bit as good as the much more widely known Gang Starr/Nice & Smooth collaboration, ‘Dwyck’), while ‘One, Two, And One More Makes Three’ is the kind of timeless party rap that generations of artists have tried and failed to carry off.

‘Hip Hop Junkies’, though, is the one that proves above all others that this album should have been a ginormous global smash. Again, simplicity is key (at least, to the album version; the single adds unnecessary additional samples in the verses) – a synth bass line, programmed fingerclicks, a nicely snapping drum loop, an irresistibly silly pop sample (the Partridge Family’s ‘I Think I Love You’, if you please), and some inspired stream-of-consciousness gibberish from Mssrs Nice ("Gregg Nice – my life’s like a fairy tale/Orca was a great big whale/I knew a fat girl who broke the scale/You won’t tay-ll, I won’t tay-ll") and Smooth ("I don’t beg ‘cos I’m not a begonia/I dress warm so that I won’t catch pneumonia/My rhymes are stronger than ammonia/I’m a diamond – you’re a cubic zirconia").

Despite Sony UK’s evident disinterest in the album, Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed was a record that had a significant impact in Britain. Perhaps because it received no marketing or promotion here, it was more easily assimilated into the choosier and more consciously underground of playlists. The group arrived with the Gang Starr imprimatur – not just the appearance of Guru on this album; a line from a track from their ’89 debut ("stick-up kids is out to tax") had been scratched up by Premier and became the hook for GS’s ’91 single ‘Just to Get a Rep’ – so already felt like they had a place in that particular milieu. And early in ’92 Gregg’s "Massive meltdown – bring the red tape" line in ‘How to Flow’ became a hook for ‘Brothers From Brentwood, LI’, a b-side but huge club anthem by EPMD, who are the duo N&S share the most obvious thematic/formal kinship with. When DJ 279 took over the rap show from Steve Wren on Choice FM, he looped the line "It’s Friday night – let’s paint the town" from ‘How to Flow’ and used it throughout ’92 and possibly beyond as part of his opening music: those seven words became an intrinsic part of a London hip hop fan’s life for the best part of two years. The album’s anthems were an inescapable part of what was, at the time, a vibrant if resolutely subterranean London rap scene. If you were there, you can’t hear ‘How to Flow’ and ‘Hip Hop Junkies’ without being transported back to some long-closed venues at odd parts of the city, and the strange atmosphere ("clubbable menace" might best sum it up, if that wasn’t such an obvious oxymoron) they all boasted. These songs went on to define their times.

But beyond so localised and personalised a response, the tracks on Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed formed an important level of substructure for what was to come globally. Rap changed in ’92, and not just at the end of the year when The Chronic arrived and permanently altered the music’s history. There was something in the air for the next year or two – a sense that hip hop could have it all, could be "outsider" music that felt tough even as it conquered the pop charts. For a while, it seemed like it didn’t have to be all one way or all the other – and that’s a sense that’s often got lost in the years since, as the music has gone global and colonised the pop mainstream but lost a lot of what made it matter. The records I hope to be writing about in these columns over the next 12 months all, to some degree, had an innate ability to straddle that divide. And whether their makers accept it or not, they all, to some degree, owed a debt of thanks to Nice & Smooth, for showing that such artistic alchemy was possible.