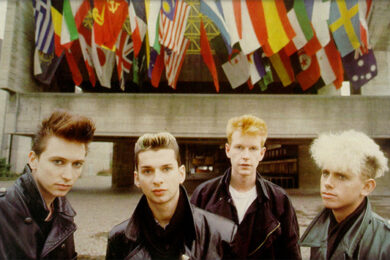

In the years since the release of their debut album, released 30 years ago next month, Depeche Mode’s roots in the Essex New Town of Basildon – a part of England that nobody talks about and which lacks the cache of Joy Division’s Manchester, The Human League’s Sheffield, or OMD’s Liverpool – has been a persistent focus of derision. With Basildon principally known for gloomy urban blight and the beer boy / Essex girl stereotype, the band have found that even those sections of the music press that have not been openly hostile to them over the last three decades have still regularly referred to them as ‘four Walters from Basildon’, representative of the ‘cult of the diamond geezer’. But with an impressive new book by ex-NME journalist Simon Spence (Just Can’t Get Enough: The Making of Depeche Mode, Jawbone Press) shedding new light on the part that their hometown played in moulding a band that would go on to sell over 100 million albums, and with a recent themed weekend in the town showing that ‘Bas’ is still the epicentre of the international cult that surrounds Depeche Mode, the place of Basildon in the band’s folklore ought to be reassessed.

Basildon, Bayeux and Bolsheviks

"I always imagine that Basildon is this great place, and that when [the band] come home there’s big parties and parades", says an American ‘Depecheist’ in the opening scene of The Posters Came From The Walls, Jeremy Deller and Nicholas Abrahams’ remarkable documentary about Depeche Mode fandom. In fact, the band’s connections to the town aren’t officially marked at all – the Council have erected no statue to honour them, and there are certainly no homecoming parades. Fans have threatened to take a marker pen to the street sign of The Gore, Basildon, and rechristen it ‘Martin L. Gore’ to remedy this lack of local appreciation. In contrast, 1000 miles away in Tallinn, Estonia, there’s a whole bar dedicated to the band, while another 500 miles to the east Depeche Mode fans march through the streets of Moscow on 9th May each year in celebration of Dave Gahan’s birthday (also Russia’s Victory Day).

There is a very clear disjuncture between Depeche Mode’s inability to shake off their associations in Britain with "nice, bland, unchallenging pop music", as performance poet Attila the Stockbroker put it in 1983, and their status as gods elsewhere in the world, particularly in an Eastern Europe that fetishised Western pop music during the years of the Iron Curtain. In Posters, a Russian fan passionately admonishes the filmmakers about this state of affairs, also offering a possible explanation for it. She says "Nobody ever loves or understands a prophet. They are always thrown out of their countries. That’s why you English are in no position to understand the greatness of Depeche Mode", before dismissively adding to the interpreter "Translate that to him, even if it’s shocking."

In Britain Basildon has been dismissed in much the same way as the band it spawned. Yet the town was (and still is) a radical place with a radical history, and a key witness to events that remade the country, 900 years apart. Following the Battle of Hastings William the Conqueror gave Bishop Odo, a character featured prominently on the Bayeux Tapestry, a manor covering what is now Basildon, tying the district to the very refounding of England in the eleventh century. Almost a millennium later, the area was at the centre of a second remaking of the country, as Basildon was born of the 1946 New Towns Act, which aimed to ease London’s post-Blitz housing crisis by building new, planned communities, remoulding the face of urban Britain. Basildon was at the avant-garde of British post-war social experimentation, symbolised by its Sir Basil Spence-designed modernist buildings, and its drastic and controversial reshaping of the landscape had echoes with communist attempts to make a new world in the East. Opposed by the villagers of Laindon, Pitsea, Dunton and Vange, Basildon New Town was the new socialist government’s vision of an engineered society, and its high-spending Labour Council, along with its brutalist architecture, led to Conservative Environment Secretary Patrick Jenkin dubbing it "Little Moscow on the Thames".

Feels Like Home

Yet Depeche Mode’s early music did not reflect the grit and bleakness which the idea of Bolshevik Basildon may evoke. It was not until they came into direct contact with the East when recording in Berlin from 1983 onwards – with Martin Gore palling up with the likes of Einstürzende Neubauten, precipitating his famous transformation into a fan of bondage wear – that the band’s sound became darker and more reflective of urban despair. Spence’s Just Can’t Get Enough paints a vivid picture of 70s Basildon as a tight-knit, supportive community which in fact offered a good measure of opportunity to the young. There was cheap housing, decent schools, nearby jobs, clean, open space and easy access to London. While kids of an alternative persuasion faced some threat of violence from the local ‘market boys’ (the band’s Andy Fletcher said "It’s very like what we call a ‘Span Town’ – spanners, beer boys"), Alison Moyet, contemporary of the band, characterises Basildon as a place that "made people creative". Anything was possible for the first generation of Basildonians because, Spence says, they came from "a town with no precedents".

Depeche Mode’s early sound was nothing if not the music of optimism. Vince Clarke called their sound ‘U.P.’ – ultra-pop. Depeche indeed brought a pure pop sensibility to the burgeoning electronic music scene in the early 80s, building on the work of pioneers like John Foxx and Gary Numan, while eschewing their earnest art school pretensions. The minimalism and urban, post-apocalyptic lyrical theme of Foxx’s debut single ‘Underpass’, for example (‘Well I used to remember / Now it’s all gone / World War something / We were somebody’s sons’) contrasted sharply with the hyperactive U.P. sound and the plain inane lyrics on the early Vince-penned hits (‘Filming and screening, I picture the scene / Filming and dreaming, dreaming of me’).

This music came out of Depeche Mode’s early training ground – a very local scene, centred around just a handful of venues in the nearby towns of Southend, Leigh-on-Sea and Rayleigh, including the Top Alex, Baron’s and Croc’s (home of the Futurist/ New Romantic Glamour Club, frequented by Rusty Egan, Steve Strange and Boy George), as well as assorted school halls, church youth clubs and pubs around Basildon. As fashions changed from 70s rock and folk to punk, Futurism and New Romanticism, all against a backdrop of Essex funk, soul and disco, budding musicians from Basildon’s disproportionately youthful population took a do-it-yourself attitude, where "Everyone would use the same equipment and cheer everybody on", according to ex-Basildon punk Rik Wheatley. The tight knit relationships that Depeche Mode forged there (not least between Martin Gore and Andy Fletcher) were psychologically formative and key to the band’s longevity, with Fletch commenting years later that their shared background still ‘shapes the feelings within the group’.

Staying Devoted

Basildon today is not what it was in the 70s. The town voted for Thatcher along with the rest of the country in 1979 and subsequently became a mirror for the economic travails of the 80s. The socialist vision of the New Town was torn apart under the ‘right to buy’ policy, the unemployment crisis hit Basildon hard and recent figures show that the town is still feeling the effects, doing significantly worse on child poverty, homelessness and educational achievement than the national average. But the feeling of community remains, not least among those who knew the band in their early years. This was highly apparent at ‘A Very Special Weekend in Bas’ – a fan convention-meets-music festival held in the town in July, organised by Deb Danahay, Vince Clarke’s girlfriend in the early days of the band and founder of the first Depeche fan club. It was at a party held for Deb at a Basildon community centre in May 1980 that Composition of Sound (the pre-Dave, proto-Depeche Mode) played their first gig, and she still flies the flag for Basildon’s part in the band’s history.

The ‘Special Weekend’ saw a reunion of the band’s childhood friends and former band mates – those who’d seen the embryonic band set up their hire purchase synths on beer crates and play gigs in their mums’ living rooms. The key figures of the late 70s / early 80s Basildon music scene were all here – Phil Burdett and Robert Marlow, respectively of Martin Gore’s early bands Norman and the Worms and French Look (which also featured Vince Clarke), Paul Langwith of Clarke’s The Plan, and Pete Hobbs and Sue Paget of Clarke’s No Romance in China – along with assorted friends, relatives and supporters. A gig at the Castle Mayne pub, former haunt of Norman and the Worms, was followed by a display of Danahay’s personal memorabilia collection at the James Hornsby School, scene of the four original Depeche Mode members’ first gig together. Tribute act Speak and Spell played the following day (Martin Gore’s fiftieth birthday), at the Q-Ball snooker hall, where the band threw annual parties for Basildon-based friends and family throughout the 80s.

But what was most striking about that weekend was the strong evidence of ‘Depechemania’, with fans from Switzerland, Poland, Sweden, Germany, France and Spain making the pilgrimage to a rainy Basildon – and some not for the first time. Forming an incongruous ‘black swarm’, these fans journeyed to the heart of the Lee Chapel South Estate to attend the Castle Mayne gig (where posters advertising the pub’s strip night suggested that we weren’t in Kansas anymore), and as the ‘very Bas’ set who had known Depeche Mode as contemporaries danced to French electropop with leather-clad Euro-goths, it became clear that this was a ‘special’ weekend indeed. With a second event, ‘Bas II’, planned for May next year, featuring Martin Gore’s nephews’ band, Basic, Basildon is becoming revived as the capital of Depeche Mode fandom.

From ‘Planet Basildon’ to the world

With Depeche Mode’s transformation from teenage synthpoppers into the dark masters of songs about emotional pain and sexual perversion, their very normal roots have become obscured. But as the birthplace of a band that went on to have such global reach, Basildon has to be taken seriously, and the town has been a key part of the band’s psyche throughout their 30 year journey. When they played to 60,453 people at the Pasadena Rose Bowl on 18th June 1988, a gig of unprecedented scale for an electronic band, and the moment when their megastar status was confirmed (takings for just this one concert were $1,360,192 and 50 cents, no less), the flight cases backstage were stencilled with the words ‘Depeche Mode, Basildon, Essex’. Dave Gahan later reflected on the spectacle of thousands swaying their arms in unison on the climactic ‘Never Let Me Down Again’, saying: ‘It was amazing – Basildon boy makes good.’ The band have not forgotten where they come from, neither have native Basildonians, nor fans across the world. So, Basildon Council – how about that statue?

Dr Sophie Deboick is a writer and historian. Find out more about her work here