A man dressed in black spins on his toes, pacing, circling his cigarette through the air. His reflection upon a wall of mirrors follows his graceful but ‘give-a-fuck’ movements, which, speeding up, turn from louche to raving: frantic swirls of arm and rolls of torso against hard wood floor. Corona’s ‘The Rhythm of the Night’ is playing. The man is Galoup (Denis Lavant), a French legionnaire, the disco is in Africa, and though now deserted but for this single performance, previously it has been populated with the collective movements of girls’ shoulders against soldiers’ chests, camera sidling into the nooks between bodies and Latin American rhythms jostling limbs. This scene is the finale to Claire Denis’ Beau travail (1999), and the culmination of military energy, identity crisis, death-desire.

Claire Denis: Music is a medium that puts body and space in relation. Music authorises the body to exist in space. That’s perhaps why the body appears central to my films – because for me, the expression of a character is described by the way he or she moves, exists. You can almost read more from a body movement than from speech.

*

A fascination with bodies characterises much of Claire Denis’ filmmaking. Bodies as marks of physical presence, bodies as means of communication, or confrontation, with our voyeuristic attraction.

CD: I tend to like the way in which the actors and actresses I work with move their body – they have a sort of a harmony. I don’t try to aestheticise this, but simply to allow the camera, and the viewer, to be with them physically. When you are casting an actor you immediately feel the presence that the body expresses, even if the actor is shy. But I don’t look at bodies, I look at people.

*

Denis negotiates the divide between self and other – a divide which the screen necessarily sets up. Us / them. Watcher / watched. She crosses this divide, places us in the territory of the Other; other sex, other skin colour, other situation. The plot of Beau travail revolves around a troop of French legionnaires training in the African desert and the often silent power-games that take place between them there. Chocolat, her breakthrough feature in 1988, is a semi-autobiographical story of a young girl of Parisian parents growing up in an Africa where the colours are piqued and the landscape spreads dustily beyond the horizon. The girl sits on the back of trucks, content to eat ants on toast in the company of her servants – her friends – while her parents remain in the background of memory. Denis has commented elsewhere that growing up so remotely it wasn’t until her teens that she entered the cinema hall regularly, when a move to Paris displaced her from her grassroots, and sat her instead before travels of the screen.

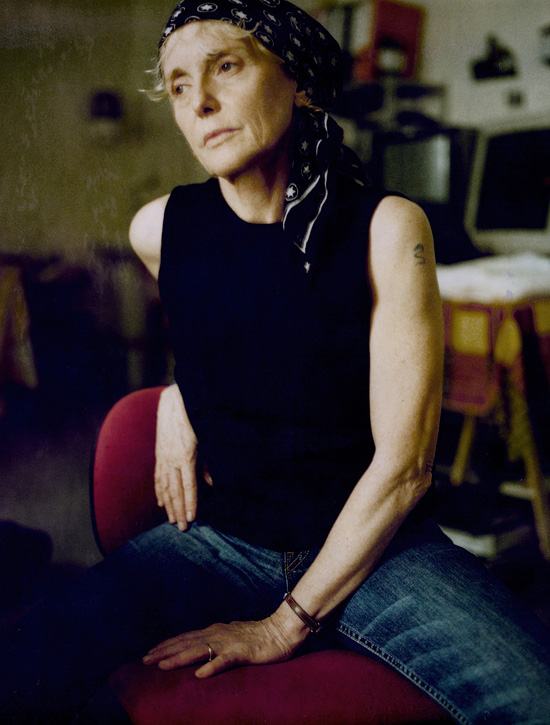

Her most recent feature, White Material (2010), written with acclaimed French-Senegalese author Marie NDiaye, revisits post-colonial questions via the threatened daily existence of a French farming family facing the antagonism of their workers. The film is visually both beautiful and brutal: pans of the bare landscape provide moments of repose from the rising tensions between the Africans and the French, tensions which spill into violence seen in close-up; into the loss of blood and the shedding of hair. Much of the film follows the movements of Isabelle Huppert’s fiercely determined character, Maria Vial, as she works the coffee fields, digs the ground, runs between home and town: a thinning white body beneath an oppressive sun.

It does often feel as though your camera stalks or follows the body, placed in an intimate position. In Trouble Every Day (2001, a strange thriller-romance with Beatrice Dalle and Vincent Gallo), for example, the camera follows the nape of the maid’s neck down the long hotel corridor. In Beau travail, the sinews of the soldiers’ torsos surprise in their beauty. Seen in terms of force, but also grace, the male body – strikingly not the female – is exposed and scrutinised as an object of watched pleasure.

CD: In Trouble Every Day, Vincent Gallo (Shane, the male protagonist) feels the maid’s presence from the moment she is introduced to the hotel room. He feels her. This is awkward for him, for his wife, for the maid. So I tried, not just to film the maid’s body, but to film her by feeling her.

For Beau travail, I was not allowed to enter the French Legion to study their training. So I had to watch from a distance, in the desert. After this, an ex-legionnaire trained us back in Paris in the kind of movements that the desert army would perform. We were rehearsing for two months in order to appear together as a group of perfect soldiers. The rehearsal took more the form of hard military training than choreography.

What you’re seeing is a realistic depiction in one sense – because the French legionnaires in the desert do train under the sun half-naked. When I told the crew before we arrived there, I’m not sure they completely believed me. In the airport of Djibouti, you see the legionnaires guarding the airport. I remember the actors being so surprised to see the legionnaires’ uniform, with really short shorts – so short that in fact that I asked the costume designer to make them a little bit longer for the film, because nobody in France would believe they were so small. What you see is the uniform of the Legion, not an exaggeration. The body is itself their uniform. Like a sculpture, it’s their identity.

When it came to shooting, in the boiling hot winds of the desert, I brought the playback of the score by Benjamin Britten [Billy Budd, from Herman Melville’s novel of the same name]. We had never used music while previously training. It was strange because it was so blowy that the actors were not sure that they could hear music, but gusts of wind with music in them. The part of Britten’s opera in the exterior training scenes speaks very much of ‘boys together’ – sailors raising the sails. It speaks of the harmony of gesture: when you raise sails on a ship everyone must be choreographed, in sync, or else you end up twisting the ship’s ropes. I think eventually it was this music that choreographed the actors’ movements.

You have also spoken of a musical rhythm in editing…

CD: Yes. Here it was the rhythm of both the desert wind and the music that effected the editing and gave a certain rhythm to the film as a whole.

*

Music played an early role in Denis’ filmmaking, with a documentary on Congolese band Les Têtes Brulées (Man No Run, 1988), and even a music video for Sonic Youth (‘Incinerate’, from the Rather Ripped album). It is music that brings Denis to the UK, to coincide with the release of a Tindersticks box set of film scores, a collection that soundtracks the long working relationship between the director and the band’s Stuart Staples. The collaboration began with Nénette et Boni (1996), a sweet kind of romance in the key of The Beach Boys’ ‘God Only Knows’, through to 35 Shots of Rum (2008), where Tindersticks’ melodies accompany the rhythm of trains over tracks against dawn to dusk skies. Amongst the band’s scores come songs already set in the popular consciousness, songs that Denis likes – the only song that is right.

Another dance scene. A version of ‘Sibonay’ plays. A middle-aged, somewhat troubled couple dance in an auberge on the outskirts of town, foreheads touching. She smiles the broadest smile, his eyes skirt occasionally elsewhere. The father dances with his daughter as the Commodores’ ‘Nightshift’ begins. The daughter dances with her love interest, a tentative embrace that ends in an awkward teen kiss. The father then dances with the proprietress, camera at their cheek to cheek, original partner distressed. A series of pairings are played out in looks and sways, without words. The dance scene is a microcosm of the quiet domesticity of 35 Shots, which tells of a Parisian train driver’s family life, its blemishes, conflicts and rituals.

If 35 Shots is a representation of the homely and familiar, Trouble Every Day, the second score on which Tindersticks worked, is un-homely, (unheimlich); intimate and other. Here we see blood, skin, the erotic-vampiric encounters of Beatrice Dalle, and we hear… chamber pop. Denis describes how she re-structured the order of the first scenes upon hearing Staples’ score, in order to open the film against the dark waters of a river at night. Yet the coupling of score and image seems incongruous.

CD: For me Trouble Every Day is a love story, not a gore film. The music was also a romance. I think the contrast between the soft music and the harshness of what we see reflects the mood that I wanted for the film. It is meant to be scary, but it is also passionate.

It’s a mutilated kind of romance, which sends the viewer back to a line from Beau travail: ‘If it weren’t for fornication and blood, we wouldn’t be here.’

*

The way Denis talks about her choices in filmmaking relate to natural chains-of-events and gradual evolutions. She uses the pronoun ‘we’ more than ‘I’, referring to director, cast and film team in one encompassing pronoun. She also talks of the film itself leading these decisions, of the film as its own creature, carving its way through image, sound and encounter. This goes contrary to any auteur-ish impulse to exercise complete control: she shrugs her shoulders like its no big deal, and trusts in the process itself.

Are you interested in being called an auteur? If Godard is an auteur, you must be a female auteur. The speaker seems to need to justify your gender in relation to the term – the term belongs to the canon, to hegemony.

CD: Your question is vast because to be ‘an auteur’ is very vague for me. It is a word I hear or read, but I never think about, when working – I never think, ‘I am, I want to be an auteur’. On the other hand, being a woman, too, I don’t think about – I’m a woman and not a man, I do what I do. The gender question – it’s hard to be a woman auteur, yes, but for me… it’s only when I come to a moment like that… with you, that I think of it. It is not something that affects my everyday life. I’m a woman, I realised probably that this was the case when I got my first period and I realised it was going to be slightly different from my brothers, and on and on, like every woman. Making films is also part of my life. So altogether, I’m making films and I’m a woman. Sometimes ‘auteur’ comes to denote a negative thing, especially in France – ‘oh, an auteur… they make serious blah blah’.

You seem in your films to stand too much on the side of the other, the marginal, to want to be assimilated as an ‘auteur’. You film from another place.

CD: Yes, the auteur’s point of view might seem a drawback for the kinds of subjects that I film. In any case, there is no choice for me, whether or not to make films.

What pushes you to keep making films? Can you conceive of ever stopping?

CD: No… bah… no. I mean, the only thing I am really eager to do is make films. I have nothing else to do. I never consider there to be an ending, as there is an end to having a job, because filmmaking creates such strange conditions for living that it is impossible to decide whether I stop or not.