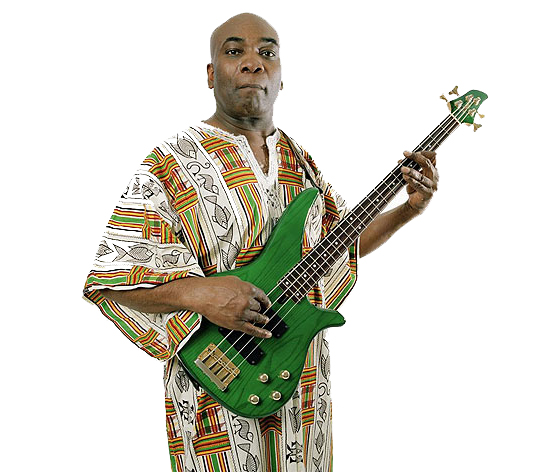

Dennis Bovell is one of the most important figures in British reggae. The stories of how he tricked soundsystem selectors into playing British (rather than purely Jamaican) reggae bands, how he shaped the birth of lover’s rock, and his appeal as part of a burgeoning British reggae scene to the punk movement, are well known. But one less happy chapter of his life is sometimes skipped over. In 1974 Bovell was imprisoned for six months as a consequence of the ‘sus laws’, the power granted to the police by the Vagrancy Act of 1824 to arrest people on suspicion of being about to commit a crime in a public place. In 70s, sus laws were revived and used to target young black men. Accounts of police behaviour in recent protests in London, and rumours that stop and search may be on its way back in, are reminiscent of this moment in British soundsystem history.

Bovell moved to London from Barbados in 1965 and "immediately landed in the soundsystem culture" because his dad had "an amplifier and a couple of boxes… in those days that was a soundsystem". His dad’s system was called Tropical Soundmaster and was contemporary with systems like Count Benji’s, Duke Reid, Sir Coxsone, Neville The Enchanter, Count Shelly, Fatman, and Duke Vin. Bovell says in those days a 10 watt amplifier was like "Wow!" By the time his generation of soundsystems was coming up in 1968/69, Coxsone, Duke Reid, Shelly’s and Neville the Enchanter were known as "the big four". Bovell’s reggae band Matumbi became part of a system called Sufferah’s Hi-Fi. His own contemporaries were the likes of Lord David, Count Nick’s, King Tubby’s, Mombasa, and Trojan. They were the black radio stations of their time.

Bovell had got involved with systems after he left school, when a friend who heard the dubplates he recorded of his band Matumbi invited them onto his system, Sufferah’s. By the mid-70s he had a residency at the club Metro in Ladbroke Grove. Two years before the Notting Hill Riots of 1976, he’d been involved in a "fracas" at the Carib club on Cricklewood Broadway, "where policemen were assaulted and the police came back and assaulted the whole club, claiming that they had arrested someone in the building and the audience had freed the guy that was arrested upon my orders.

"They said, not then but afterwards at the trial I found out, that they had arrested someone for suspicious driving of a vehicle on the outside of the club and the person had run into the club and they chased the person into the club and apprehended the person in the toilets. And as they were bringing the person out of the toilet where they had arrested him, members of the audience set about them and set free the person, assaulted police officers, and then the police officers ran out of the club, went and got reinforcements, came back and kicked everybody else’s head in."

Really nastily? "Yeh. Dogs bit people, all sorts, right? Out of that, they arrested 12, 11… no they arrested 10 people. The other two people who were charged was me, and my mate with the soundsystem, and he was charged because he stood surety for me when I got charged with ‘causing an affray’. I was wrongly accused by police officers of stirring up trouble between the police and the audience. I didn’t do it."

Bovell had had the misfortune of being a successful soundman at a time antagonism with the police was finding its way into reggae music. One of the deejays on the mic at the event had started encouraging the crowd with anti-police chat. "During the time of the fracas, there were three soundsystems in the place," he says. "I was the most popular of the three. One of the other soundsystems was actively engaged in anti-police mouthing off on his system. He actually played this record ‘Beat Down Babylon’. That was all attributed to me. What I didn’t do, was to go and say, ‘No no no no no, that wasn’t me that was him!’ My point was, ‘It wasn’t me and I’m not saying who it was.’ Because if I’d had said, ‘It was him’, I’d have had to have gone to court and stood in the witness box and said, ‘It was you, you did it.’ Right? Where am I gonna go after that, in the community of soundsystems?

"It’s better to keep your mouth shut, really. I mean, that person’s now dead and it wouldn’t be fair to say that it was him without giving him the chance to defend himself, but I know it was him, with all the anti-police talk on the soundsystems. But when people were asked who it was, automatically they said it was Sufferah’s. Why, I don’t know."

It was probably a compliment. "Ha ha – one I could have done without! Because people had said, ‘Oh who was that on the microphone… oh that was Sufferah.’ And it wasn’t. So when I was called up to say, ‘We’ve been told that you were geeing up the crowd, obviously I said it weren’t me. To this day if you wanted me to take a lie detector test I could take that test quite happily, cus it weren’t me. But no, they never gave me one, they never even give me the benefit of the doubt, mate. Because at the end of the trial, nine people were acquitted and three people had a hung jury, of that three people I was one of them, and the laws of this country state that a man is innocent until he’s been proven guilty.

"My standpoint is that I wasn’t proven guilty so therefore innocence must have been mine. But instead of giving me the benefit of the doubt and affording me what British law says, they moved the goalposts and said, ‘You’re gonna be retried for this.’ So I was retried again. Even after the first case was that 12 people were charged for causing this affray, nine of them were acquitted, because we didn’t even know each other until we were on trial, and we were supposed to have been some kind of gang that attacked the police. And I was supposed to be the bloody ringleader. I didn’t even know any of the people that I was charged with."

The cost of the trial is pretty ironic in the light of recent public funding cuts. "It happened in 1974 but it took two trials at the Old Bailey, one of nine months and one of three months, before I got convicted on a majority of ten to two. And spending some five hundred grand of taxpayers’ money, and wasting some nine months of my time. I couldn’t work because I was at court 9-4, I couldn’t sign on even." Bovell then tells me he lived off selling dubplates. When I bring up the Junior Byles record at the centre of the fracas he explains "Babylon is supposed to be the Biblical, the ultra-evil. Babylon is the system, is anything bad. The fact the police were nicknamed Babylon was because … they’ll have to face up to the fact that some policemen in this country have done some horrendously evil things."

I point out that stop and search has been declared illegal and Bovell says, "Well, that means that all the people who have been stopped and searched before should have been issued with the Queen’s pardon, and anyone who was criminalised with it should be exonerated. But they won’t do that.

"The Metropolitan police have to understand that they’re not the only police force in the world, and when people are saying this about the police they’re probably talking about the Jamaican police. Because they are horrendous, some of them are a law unto themselves. American police, police in general all over the world do shit things to people that as the protectorate they ought not to do."

Bovell was released in time for the Notting Hill Carnival of 1976. "They sent me to prison for three years for this crime I didn’t commit. I was in prison for six months until my appeal came to the Central Criminal Court. At that appeal I was set free. My conviction was overturned and I was free to go. I spent six months of my life in Wormwood Scrubs and nine months on trial. So all in all about a year and a half of my time was taken up with this false accusation. When I came out of prison, it was a day or week or so before carnival. So I was on my way there with this famous Jamaican DJ called I-Roy, and he’d just bought this new 3,000 Ford Capri, like a racing car, it was a white one. And we drove down to the carnival and as we were driving along Notting Hill we saw police retreating under a hail of bottles. And I’d just come out of prison. So, it was time not to go to carnival."

A lot has changed since, but Bovell’s story is one to remember at a time of kettles and the police asking for increased stop and search powers. The policeman who gave evidence against at his trial was discovered to have been involved in other corrupt behaviour and to found have given false evidence against Bovell. The film Babylon, which Bovell made the soundtrack for, was originally intended to be based on what happened at Carib club, but events were fictionalised because "I wanted to forget it as quickly as possible". The film was rated X because of the amount of ganja it featured (apparently Brinsley Forde had to shoot a scene where he goes into a rasta temple and smokes a chalice four times, by which point he was incapable of shooting it again because he was so wasted).

Bovell went on to a proliferous career working with artists from Alpha Blondy to Bananarama. Sat in front of him you can’t help but marvel how much change he has lived through. He lightheartedly disparages what he calls dancehall’s repetitiousness, "batty rider" attitudes in hip hop and Alicia Keys’ tendency to sing out of tune. He also doesn’t think that fast-chat jungle MCs were actually saying any words at all and laughs about the noise levels on current soundsystems.

"The attraction to soundsystems in the beginning was, who could be the heaviest. Not the loudest. But the heaviest, with quality. And then it became not who could be the heaviest but who could be the loudest and to make people’s ears bleed. To enjoy sounds at those levels you’d have to be off your face, to not notice that your ears are being damaged. I’ve said to people, they measure sound in kilohertz, because the higher it is in frequency, the more it hurts and the more likely it is to kill you, or to kill your hearing!" He advocates a good balance of treble and bass – lots of treble, combined with alcohol or drugs, producers anger "and that’s causing a lot of grief among youngsters because they’re angry without knowing why".

It’s a shame, then, that student protestors are unlikely to be able to source valve soundsystems, which have a distinct, warm vibration because the electric valves (like lightbulbs) that they use to transmit frequencies need to be warmed up. But if you want to experience the valve sound, you can go and catch Bovell’s friend Shaka. Bovell, meanwhile, still produces and tours the world with dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson ("We haven’t done Hawaii!"), and he lives in North East London.

Reggae Britannia will take place on February 5 at Barbican Hall and will feature the likes of Dennis Alcapone and Winston Reedy, Dave Barker, Pauline Black, Ken Boothe, Ali Campbell, Brinsley Forde, Janet Kay, Neville Staple, Caroll Thompson, Big Youth and Dennis Bovell. For more information, click here. And coming tomorrow on The Quietus: A preview of the Reggae Britannia series on BBC 4, starting from February 11.