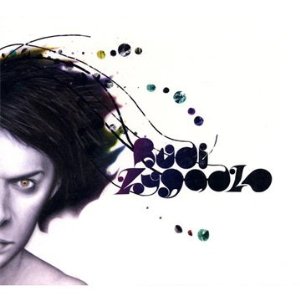

Dubstep is an uprooted, bohemian milieu, or so the observations of some would have it. If anyone is apt to feel uncomfortable with the suggestion – of disaffiliation with the grass roots of successive UK scenes – it’s fair to assume it wouldn’t be Rudi Zygadlo. On his first album, Great Western Laymen, it’s if the young Scotsman takes the notion and runs with it, wilfully into the jaws of practically conservatoire-savvy art-pop.

In his sensitive musicianship and use of his own singing voice, he could well invite comparison to James Blake, for the two represent a romantic kind of figure haunting the genre’s margins. Yet though both abstract part of their vocabulary from a common source, Zygadlo’s album is a different proposition. Apparently far from a laptop boffin, instead of tweaking his way to desired results his method constitutes an elaborate cross-stitch of untreated, often live instrumentation. More than that, he’s comfortable performing an unlikely kind of alchemy on elements of dubstep’s lumpen, populist incarnation, not to mention working in bold borrowings from synthetic disco, jazz and classical music.

On paper, the concoction is perhaps not ripe with appeal, but surprisingly it does deserve to be sampled: Great Western Laymen is not only a very palatable listen, but a rather compulsive one. It reflects a particular talent that one has to pause to recognise the oddness of the concept, which is unobtrusive in the flesh. All thirteen songs cohere and progress easily – the record is no curate’s egg and it fits that its genesis, according to Zygadlo, was relatively swift.

He treads confidently away from a number of mistakes sceptical listeners might anticipate. There is no attempt to match the impact of dubstep on its own terms, whether in the form of comic bass protuberance or sparse shock-outs. While wobbly filter-frequency oscillations and pitch contortions are deployed in a certain fashion, their function is to nimbly accent the dynamics of the songwriting as opposed to cheapening or obliterating it. Nor, on the other hand, does there appear to be any pretension signposted in passages styled after chamber music, or in titular nods to Bulgakov and (weirdly) some form of Latin Mass – the impression is more one simply of thoughtfulness. There’s also a charm in the way the ambiguous, yearning qualities found in disco and synth-pop are prized above any sense of glamour.

There isn’t always an entirely prepossessing song to be found at the core of Zygadlo’s music, but the effect of the whole is consistently rewarding. For all the neatness of its specific synergy, he might still be imagined as a dabbler, sufficiently mercurial maybe to clothe his compositions in a free selection of stylistic affects. If this prompts the question why he should dip into these chosen ponds, one answer is that few others, presumably, would think of attempting to pull it off. Even fewer, it seems likely, would be capable. Apart from that, it would be a shame to deny this intriguing album the chance to speak for its own qualities.