Pop music is full of auditory trompe l’oeils, the rush of hearing something for the first time that in reality is perhaps not as breathtaking as it initially seems. Returning to records years after their release can sometimes reveal the weaknesses that we’d failed to notice at the time. What seemed refreshing or innovative can, further down the line, appear primitive or tiresome. There’s a moment that used to give me goosebumps in The Blue Nile’s ‘The Downtown Lights’, when the guitars shimmer like heat off a roof, which now almost makes me cringe, the sound having become over-familiar thanks to its use in sometimes less than welcome contexts over the years that followed. The reiteration of themes and tropes, whether by their inventors or subsequent imitators, offers diminishing returns. But we can’t simply hold our nostalgia responsible for the fact that records from the past sometimes, upon reinvestigation, sound dated. Technology, too, is to blame: it often makes available to all what was once accessible only to those with the imagination to create it. And technology also renders previous developments redundant: my first Walkman’s stereo sound was mindblowing, but compared to what my new Bose headphones can pull from even the most basic apparatus it likely sounds like an old Gramophone.

And so it is that the recollection of Virgin And Philistines‘ singles – ‘Thinking Of You’, ‘Castles In The Air’ – and its other standout moments have cultivated its candid melancholy and perversely perky pop, while the reality of listening to it exposes the tricks that memory plays as much as how fashions have changed. At the time it seemed a breath of fresh air, a semi-acoustic pastoral antidote to the neon pop landscape that surrounded it. Retrospectively, however, it sounds mildly overpolished, occasionally too close to the domain of session musicians playing along to click tracks, its steely (Dan) sheen a hurdle perhaps too great for some who didn’t live through its historical context. You’ll find the same problem with Aztec Camera, or Prefab Sprout, or The Lilac Time. But those who can accept this will find within its pristine forty minutes some of Hall’s finest moments, lyrically and melodically, more than enough grounds for any latent nostalgia.

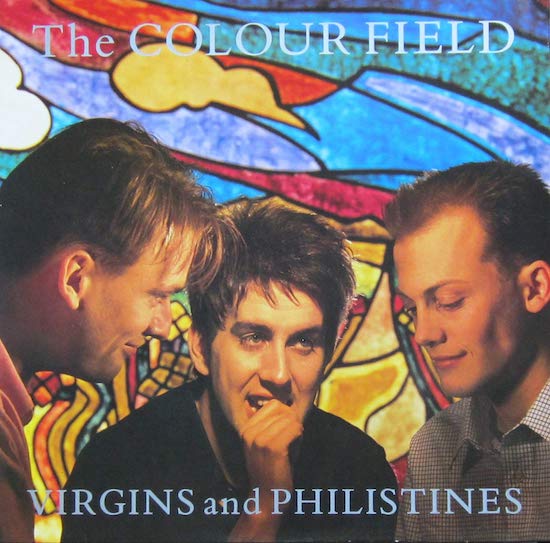

Terry Hall seems to understand the way that familiarity can breed contempt. He’s spent his career moving from one project to another, restlessly shaking things up, never staying with collaborators long enough for things to become stale. Virgins and Philistines may sound archaic, but that’s more the fault of the pale clones that followed in its wake. Making allowances for its technical approach is imperative, especially since its intentions remain clear, and when he pursued the idea with its follow-up, Deception, he soon realised that he’d reached a creative brick wall and called it quits. In fact Hall has never made more than two albums under any of the many guises under which he has operated. He bailed from The Specials in 1981 as ‘Ghost Town’ sat atop the charts, taking Lynval Golding and Neville Staples with him to form Fun Boy Three. He called time on Fun Boy Three within two years, despite further hits, and The Colourfield were born, his collaborators this time Toby Lyons and Karl Shal (of Swinging Cats). They in turn dissolved during the recording of their second album, and Hall moved onto further experiments: two solo albums, collaboration with Dave Stewart under the name Vegas, further collaborations with (amongst others) Fundamental’s Mushtaq, Damon Albarn, Tricky, Dub Pistols, The Lightning Seeds, and the rather painfully named (and oft forgotten) Terry, Blair, and Anouchka.

It was on the latter’s ‘Lucky In Luv’ that he sang "If life was fair / I’d be a millionaire", and, to be honest, given the affection in which he’s generally held – underlined by the recent Specials reunion – it’s a little surprising that he isn’t. (Perhaps he is and simply doesn’t flaunt it, in which case the man deserves even more respect.) But one of the reasons for the high regard people have for Terry Hall is precisely that he’s never allowed us to become bored of his work. Its only constant is his doleful voice, its shortcomings at the heart of its charm. As soon as there’s a danger that whatever he’s working on might become formulaic he’s taken another left turn, and with this has come the unspoken suggestion that we too should leave his previous activities behind.

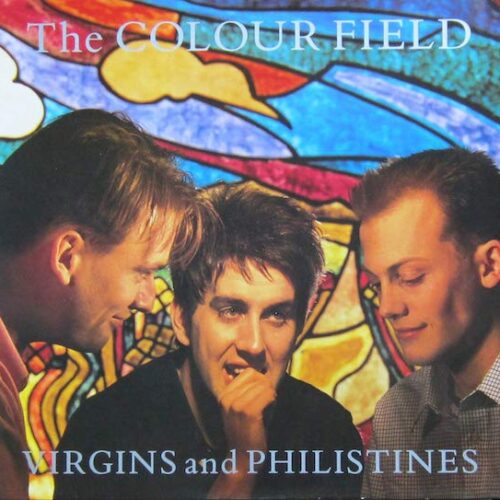

The Colourfield were one of those left behind. Two albums, a handful of singles that grazed the charts and a bunch of fuzzy videos on youtube are all that remain of this briefly wonderful exercise. The second album, frankly, is a mess, a painfully overproduced synthetic nightmare that could almost pass as part of the PWL catalogue. It’s hardly surprising Hall left the project behind, and little wonder that he looks especially morose – even by his own standards – on its cover. But 1985’s Virgins And Philistines is something else, and its reissue by Cherry Red – making it available on CD for the first time – is good reason to revisit it.

Virgins And Philistines‘ overwhelming mood is, true to form, that of imminent regret, the foreshadowing of things going wrong or at the very least not working out as hoped if, indeed, it’s not already too late. For the most part it’s focussed on domestic affairs, as though Hall has just emerged from a series of painful failed relationships. At its most optimistic, "romance is a word that should be seen but not heard" consisting merely of "castles in the air", and even that often seems a forlorn hope: Hall’s seen "the world about us / and the Disneyland dream’s a lie" (‘Cruel Circus’). Even the lovelorn sentiments of ‘Thinking Of You’ are undermined by the slowly dawning reality that the object of his desire is resistant to his sentiments, assuming they’ve not walked away previously anyway: "I could be the one thing there in your hour of need / So if you decide to change your views I’m thinking of you". At times, however, it broadens its reach to address social affairs: ‘Cruel Circus” refers to "fur coats on ugly people expensively dressed up to kill / In a sport that’s legal within the minds of the mentally ill", while on ‘Faint Hearts’ he asks, "Will all this wishful thinking save your ship from sinking?"

In fact the number of lines that bear repeating here confirm that this was Hall at his most articulate, his attention to details as striking as Morrissey’s, his ear for a wry observation never more finely tuned. "I was travelling to nowhere when I fell off the rails" (‘Sorry’), "You took the good from the bad like the 36 pieces of cheap cutlery" (‘Take’), "I really wanted her hair to touch her knees / I really wanted to share forgotten dreams" (‘Castles In The Air’), "You can take me for a ride / but only if I get the window seat" (‘Armchair Theatre’): the examples are legion.

But the music – for the most part – matches this eloquence. On occasions, in fact, it’s a masterclass in songwriting. ‘Thinking Of You’ recalls Bacharach and David’s ‘Do You Know The Way To San Jose’ in its use of Spanish influences, its seemingly upbeat, almost coquettish melody at odds with its despondent lyrical tone. ‘Faint Hearts’ has hints of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘Carousel Waltz’, Hall’s voice at its most yearning as he reaches for the top notes, Toby Lyons’ organ wheezing much as Steve Winwood’s did on Talk Talk’s The Colour Of Spring. ‘Castles In The Air’, meanwhile sports castanets and flourishes of flamenco, an autumnal melody, dramatic cello strokes and a guitar solo that, under most circumstances, would drag a song to the depths of hell but which here lift it into that blue haze between bitter and sweet. ‘Take’ may seem a little clunky in comparison, but its awkwardness matches Hall’s mood as he battles blatant belligerence with brutal honesty, the tremor in his voice challenged by the defiant self-denial at the song’s heart ("Me and the cat own the lease on the flat / And nothing you do will ever change that… / You could say that we’re having the time of our lives.") ‘Cruel Circus’ even breaks unexpectedly, delightfully, comically into a music hall bridge, the sampled sounds of ducks, chickens and horses interrupting his pleading "Isn’t it enough to eat them?" while ‘Yours Sincerely’ is a deftly tender tune with which one suspects Kings Of Convenience may be familiar, though whether they’re capable of lines like "I took the wrong decision / So you turned on your ignition" is open to question. And then there’s ‘Armchair Theatre’, which alternates between the sincere, the twee and a knowing banality, highlighted by the way Hall delivers the line "I’m getting very bored indeed".

But it’s actually a cover of The Roches’ ‘Hammond Song’ that steals the show, still sounding as magnificently heartfelt today as it did 35 years ago. Against gently strummed steel guitar strings, Hall shifts his attention from his own relationships to the naïve love of one younger than him who’s leaving town for someone he considers unworthy, much as McCartney did on ‘She’s Leaving Home’. It’s gentle, poignant and exquisitely understated, not a million miles from Simon & Garfunkel’s gentler moments, while its lush harmonies recall another hit of the time, Godley and Creme’s ‘Cry’.

Winning new converts to Virgins And Philistines might be hard: quite apart from the production, its heart-on-the-sleeve sentimentality may be simply too saccharine in cynical times. But that’s the danger of baring your soul, and Terry Hall never did it quite so beautifully as he did here. Like "the ghost of your love (that) will never die" in ‘Yours Sincerely’, its memory and wistful thinking still haunt those who experienced it. What we remember may not be quite what we find, but since nostalgia lies at its heart, let nostalgia be its reward.