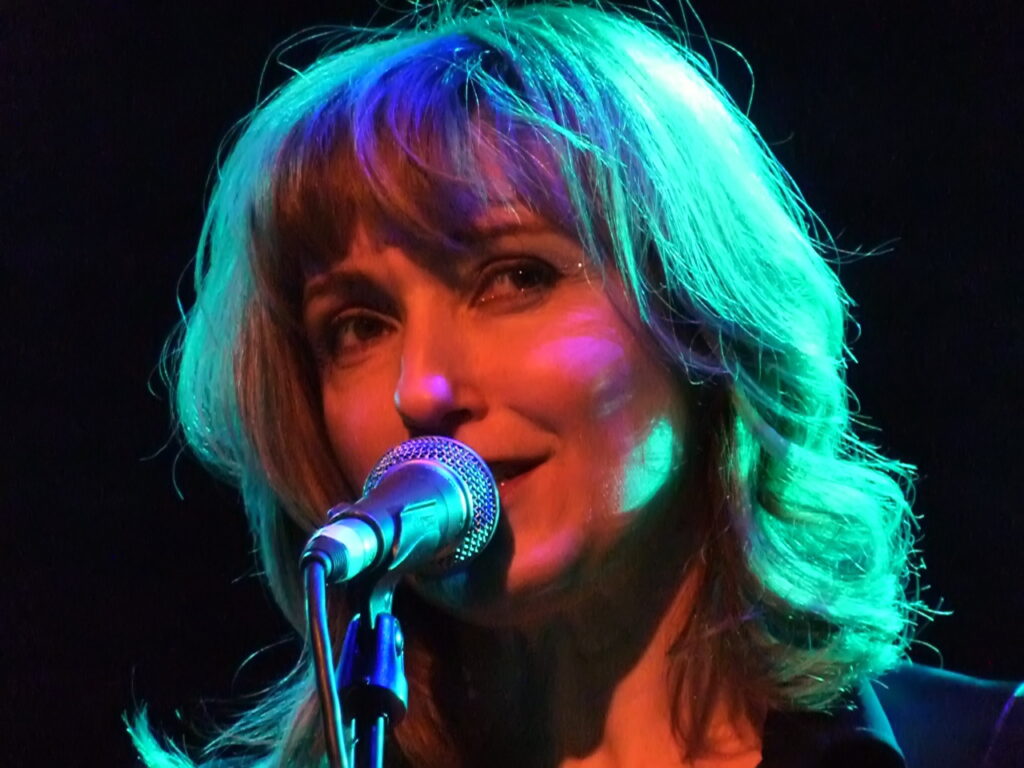

In the cosy confines of Borough’s Gladstone pub, Viv Albertine is singing a song, a percussive Nico-like chant in which she declares: "I believe in granite/ I believe in mud/ I believe in mountains/ I don’t believe in love." As the performance comes to an end, her eyes appear to have welled up, an odd contrast to the song’s denial of emotion. The second track from her excellent new Flesh EP, out on Thurston Moore’s Ecstatic Peace label, it’s the most affecting moment in a set which has its bumps evened out by assurance and humour. "Legends do that, you know," she tells the audience after forgetting her guitar capo. Later she warns: "Here’s where it all comes out. Confessions of a milf."

Certainly the most glamorous of The Slits, Albertine quit music for film school and directing and raised a daughter before the chance to play with her old band came up in 2008. She’s here solo after choosing not to go down to reunion route taken by former bandmates Ari Up and Tessa Pollit. When we interviewed them a few months back, they didn’t want to comment on her fledgling solo career – but they spoke of her with affection: "She was really articulate and really cutting and really caustic," said Pollit. Perhaps Albertine’s not as acerbic as she was back then (fine by us) but she’s a bright-eyed, engaging conversationalist, as willing to talk about the old days as the new. Judging by the size of the venues she’s tackling, there are still plenty of dues still to be earned, but the post-Slits-y lo-fi and lyrical honesty of Flesh ("I’m quite shocked about some of the things I think now," she tells us) should win her more than a few followers.

You’ve said you were traumatised when The Slits split up in 1981. Why was that?

Viv Albertine: We went everywhere together, we were like sisters in a gang. We were just absolutely knitted together and for all the pain of that – the squabbles, the competition between us as girls – at the same time, we were as one. After losing that identity overnight, I had to rebuild Viv Albertine as a person. That purpose, to make people understand about The Slits, had been my mission every day and that had gone. It’s not like it was a mission that I was broken-hearted to let go of because I didn’t believe in it any more anyway, but it was a painful separation, like a terrible break-up between lovers.

And you didn’t listen to music for three years afterwards?

VA: Music was my life and it was gone. Keith Levene, who I grew up with, was the same after PiL broke up, he was so broken-hearted.

Has the way it ended coloured your memories of the band?

VA: No, because it didn’t end in a horrible big argument, us trying to stab each other or anything. Things just shifted: Ari was pregnant, musically we didn’t fire off each other and financially everything changed. Thatcher got in, people were making music to make money and it was totally not the medium to be in any more. The Slits didn’t fit in that. It was a natural end, just like in a relationship, but that didn’t make it easy. Humans find it so hard to let go, even if it’s the best thing to do. These invisible ties we have to things.

What made you decide to get back into music?

VA: I never in a million years thought I’d ever play again. I thought, I’ve done that, it’s passed. Then this thing happened where I just felt a shift. We were so sectarian about what we liked when we were young, but I suddenly felt like people were open to all types of music again. Zoë Street Howe [Quietus writer who was writing a book about The Slits] came into my life, and the fact that a girl as intelligent and knowledgeable as her thought The Slits were relevant had a huge effect on me.

Tessa asked me to come and play with the band, but told me I had four months to learn all the songs again. I hadn’t touched a guitar in 25 years! I got a Squier from the guy down the road and sat at the kitchen table, and my husband’s going, "You’re fucking mad, what are you doing?" But I’d been here before. In the Slits days, people I knew, good mates, said to me: "Viv, you can’t play, stop it, go and do something else." For people to say it to me again now, I was like, I’ve heard that before and look what happened. You idiots. Don’t underestimate me.

So I just plonked away for about six weeks or so and then one day as I played, I just sort of lost it and my hands started going mental. From somewhere the old style of Viv playing came, the weird, slightly atonal, slightly oriental thing that I do, and I wrote a song. Then it was like an avalanche, the songs just came pouring out. I became like a teenage boy, who had to be in his room playing every day. Nothing else mattered. It’s quite strange for a woman of a certain age to feel like this and I realised I hadn’t known what was going on in myself until it all came flying out from the guitar. I hadn’t realised how fucked up I was.

By the time I went on stage with The Slits in 2008, I’d written all these songs and played some gigs in small pubs and it didn’t feel strange to be on stage with them. But I didn’t feel any affinity to what The Slits were doing, which I wouldn’t have known if I hadn’t been doing my own stuff. The songs were great, but I couldn’t be singing something I wrote that long ago, because it’s just not relevant now, to me.

The new EP is pretty personal – was it challenging to bare your soul like that?

VA: I was horribly honest and it was a hard thing to do, because people around me weren’t happy about that. But as I said to my husband, there’s no point in doing it if I’m not telling the absolute truth about my situation. If you say what you really think and you fail, you have no shame. There’s absolutely no choice, I had to say what was happening, I had to say what I was going through…

What was happening, what were you going through?

VA: [Laughs] I don’t know how deeply I want to go into it, it’s in the songs, but… a total reassessing of life. Not only my life and how I was living it, but all my thoughts and concepts about love and life got turned on their head, because I’d reached a certain age, I’d gone through a marriage, I’d had a child, I’d loved, I’d lost.

On one of the tracks on the EP, you sing, "I don’t believe in love…"

VA: Yeah. My dad died and I wrote that song the day I found out. We’d had a very difficult and fairly estranged relationship, so it wasn’t like I grieved him dying – I’d grieved a very long time ago. But the possibility that I’d ever have that nice dad who loved me and who I loved had gone. I started ruminating on love. Did he love me? Then I started thinking, has anyone ever really loved me? Have I really ever loved anyone? Is it actually just a made-up construct? I was in an emotional state that day and I just thought, fuck it, I’m not going to believe in this shit any more, I’m just going to believe in what I can see and what I can touch.

Was that a passing phase or…?

VA: No, I’m still… I’m still really, really reassessing love. I don’t know if it’s ‘cos I’m a girl, if it’s because I’ve been raised on these bloody books and these fairy stories. I’ve got a 10-year-old daughter who’s being brought up on a lot of that rubbish as well. I just don’t want to be duped. I’m probably the most romantic idiot you’ll ever come across, and all my life I’ve wanted and hoped and believed in the big love and the soulmate and… I’ve lived with that concept since I was about nine-years-old, and believed in it since I discovered The Beatles. I’ve listened to the words of every song I’ve ever heard believing in it. If I’m going to let that go – and I am kind of letting that concept go – it’s terrible for me. It’s like my religion gone. But at the same time, comes the birth of something else. I don’t what that will be yet, whether it’s a more practical or a more honest way of living. Maybe out of the… I don’t know, the dregs…

The ashes.

VA: The ashes, exactly, will grow something more real and I’ll go to my next phase of life. Maybe it needed to be trashed. When you experience the death of a parent, whether you’re close to them or not, you reassess your life, because you see an arc that’s part of you. I saw my father’s arc of life and it had a profound effect. And that’s the gift they leave you, if you choose to take it.

Keith Levene originally taught you to play the guitar – what did you learn from him?

VA: Keith’s the most sensitive person I’ve ever met in my life, man or woman. He can feel vibes in a room, he can practically read minds, so he was an incredibly intuitive teacher and helped me channel myself through the guitar. But also, one thing about Keith was that he said: "You must start with the guitar in tune. I don’t care what the fuck you do with it afterwards, but start with that guitar in tune." And he still says that today. No matter what he plays, no matter how ugly, mechanical or industrial the noises he pulls out of that guitar, it’s got to be in tune. Isn’t that funny?

Yeah! Do you still see him?

VA: I saw quite a lot of him last year and we did actually try to start a band together, but it didn’t work out. We’ve known each other so long, we’re more like brother and sister, squabbling away. [Laughs] No, but he’s an amazing guy, still.

You went out with Mick Jones from The Clash – did he teach you any guitar?

VA: I always think as soon as you sleep with a guy, he never teaches you anything – you’re only actually learning with guys who want to sleep with you… Of course, me and Mick met at art school before I played guitar, so he wasn’t going to teach me anything, he already had me. But I would see Mick every day on the pay phone in the lobby all day long, arranging rehearsals and so on, shoving money into that pay phone; what he did teach me, without knowing it, was how to run a band. There’s always one in the band who does that – who takes all the responsibility, the love of the band and the work of the band.

Mick’s very supportive and a humble, nice guy. All through the whole punk thing, which had very strong ways of thinking, he kept to his own thoughts, he didn’t follow the crowd. Malcolm and Vivien were like the priest and priestess of it all, and I was interested in their unusual takes on things, like, we don’t believe in love, or sex is just squelching about or whatever – but Mick had such a thinking, intelligent mind, he wasn’t swayed by the latest wave of thinking or what was trendy. That’s what’s so great about Mick. Yeah. Brain in there.

Before The Slits, you and Sid Vicious were in The Flowers of Romance, which must be one of the most famous bands never to have actually recorded anything or played a gig – can you tell us a little about them?

VA: The first time first time I met Sid, we were outside a pub and even though I couldn’t play I said, "I wanna get a band together," and he immediately said, "Oh, I’ll be in a band with you." And I was so touched, because at that time, guys didn’t want to do what girls did. For a cool guy like Sid to want to be in a band with a girl was forward-thinking. I don’t think Johnny Rotten, Mick, or any of those other guys would’ve answered that.

We arranged to meet, went to a squat and rehearsed all through the summer of 1976 – the hottest summer on record for a long time – and emerged at the end of it absolutely white, and without one song. Nothing. [Cracks up] And we were in that basement for hours every day. I remember Sid jumping up and down, doing that pogo thing, tooting away on the sax, and Palmolive [Paloma Romero who later joined The Slits and the Raincoats] was on drums for a bit, and a girl called Sarah [Hall] on bass. I couldn’t play guitar at that stage and we were thrashing about and it’d be a bit embarrassing. And that was it, the whole summer, nothing, not one song.

Is there a side of Sid we don’t hear about, do you think?

VA: I think it’s been readdressed a bit more now, that he wasn’t an oaf. He was probably the most broad-minded person I’ve ever met: he could keep two hugely diverse views in his head and accept them both. I don’t really know anyone else who could do that. So open. And he was so open he took anything that came, whether it was heroin or Nancy Spungen or whatever.

John Lydon recently said he regretted bringing Sid to the Sex Pistols…

VA: Well, he just went for it, didn’t he? I remember me and Sid watching the Pistols at The Screen on the Green and saying, "Oh my God, this band is the best band we’ve ever seen and will ever see, and what is the point of ever doing anything musical now we’ve seen them?" Because if you can’t be better than them, what’s the point? And about a week later, John did ask him to be in the band, and he said: "Should I do it?" I said: "Hell yeah, of course, you must." And he knew he couldn’t turn it down. But he did actually think about it – whether he should do his own thing, or go into something that was already happening and he hadn’t really been a part of. But he did it and… I don’t know, that’s just Sid. Just took it to an extreme.

Viv Albertine’s Flesh EP is released on 1 March through Ecstatic Peace – listen to tracks here