In pop music, everything eventually becomes heritage. And when any given act becomes successful enough, even their failures are forgiven and welcomed into the canon. Bowie had many false starts before his career truly took flight in the early 70s, but the conventional reading is that this, his second album, is where it all started to come together. It’s not quite, but it’s certainly worth re-investigating.

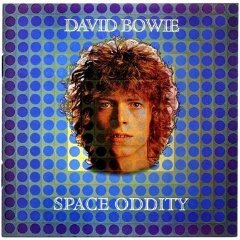

The album’s genesis was somewhat convoluted. Bowie’s (largely dreadful) eponymous debut LP of 1967 had been such a monumental flop that this record was also initially released with the title "David Bowie". Presumably, the reasoning was that to confuse the two, you would have had to have known the first existed, which few did. It acquired its current title when first re-issued at the height of Ziggy-mania in 1972, and has been regularly repackaged since.

Having been quietly dropped from the Deram label in 1968, the career-saving ace up Bowie’s sleeve was the song ‘Space Oddity’ itself, a demo tape of which had persuaded Mercury Records to take a punt on an album deal. However, contemporary recollections do not hint at the song’s now-classic status. Bowie’s then-manager Kenneth Pitt spent a while fruitlessly trying to persuade an unimpressed George Martin to produce the track, before turning to Tony Visconti. Visconti in turn loathed the song so deeply that he handed the job to engineering assistant Gus Dudgeon, in order to focus on what he saw as the superior album material. And despite it being a huge hit in the summer of 1969, both the song and Bowie himself were widely seen as little more than a novelty cash-in on the imminent first moon landing.

That said, no doubt Mercury would have been much happier with more such "novelty" hits, rather than the uneven, gloomy LP Bowie and Visconti finally delivered, a record for which the phrase "I’m not hearing a single" could have been invented. By the end of the sessions, there was nothing in the can remotely accessible as ‘…Oddity’ and the label largely lost interest in promoting the record, which bombed hard on both sides of the Atlantic, despite receiving some ecstatic reviews.

It was not until the following year’s The Man Who Sold The World that Bowie would (with the aid of Mick Ronson’s guitar) synthesise a coherent and commercially viable style of his own, and Space Oddity flirts equally with 60’s Bee Gees epic pop, English folk, Bo Didley-esque rock and roll and Dylan-influenced protest song. The press release valiantly describes this whack-a-mole approach as "genre-defying", which is a true, but perhaps overly-generous description. More realistically, like a drunk and horny used-car salesman at a provincial business conference, it doesn’t really care who it goes home with, as long as it’s with someone, with a whiff of desperate opportunism to the incoherence of its various come-ons.

It is testament to Bowie’s growing skills as a writer and a stylist that while some of these efforts are unconvincing, the whole remains a largely compelling listen. In truth, there’s only really one stinker here, which is the lumbering, over-long horrid folk-prog protest song ‘Cygnet Committee’. Bowie – tellingly not yet aware that this was not his forte – regarded it as the best song on the album, and described it as "a song in which I had something to say. It’s me looking at the hippy movement, saying how it started off so well, but went wrong when the hippies became like everyone else, materialistic and selfish."

This was, at the time, a subject which greatly exercised the young Bowie. Having become disillusioned with the hippy movement in general, and his own Beckenham Arts Lab group in particular, he had reportedly spent much of a festival the group had organised bitterly arguing with other members (including his future wife Angela) that they were "materialistic arseholes" for treating the event as a commercial venture.

The notion of Bowie as a rootsy opponent of commercialism is, of course, something of a stretch, and he covers the same ground more personally, more ambivalently and to greater effect on the album’s closer, ‘Memory of a Free Festival’. Over a mournful organ backing with no other instrumentation, he ruefully reflects "It was ragged and naive, it was heaven". The song is an early study of the clash between the weaknesses of youth culture and its irresistible attractions that was to later form one of the conceptual tent-poles of Ziggy Stardust.

‘. . . Oddity’ itself remains an impressive song; on the surface, it’s markedly ambivalent about the United States’ victory in the space race, and given the jubilation that surrounded the event, serves as an excellent metaphor for social alienation, and a prescient look forward to Bowie’s deeply conflicted relationship with the fame and adulation he was to receive in the 70s. However, the true stand-outs are the tracks which most clearly point the way forward.

‘Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud’ is light-years ahead of the rest of the LP in terms of sonic ambition, with a lavish orchestral arrangement and skyscraping chorus that anticipate Hunky Dory‘s ‘Life On Mars?’. Lyrically, the song is harder to praise, being an impenetrable fantasy narrative about a prophet-like figure living on the mountain Freecloud, and the unbelieving villagers who bring the wrath of an avalanche down on them. It’s all very silly, and the kind of thing his friend Marc Bolan would pull off with a wink where Bowie’s earnest delivery elevates the whole thing to unintentional comedy. Still, though, if grandiose psychedelia is your thing, this is a beguiling example of the form.

More ramshackle, but probably the most significant track here, is the juddering swagger of ‘Unwashed And Somewhat Slightly Dazed’. Bowie’s disaffection with the folky, hippy-ish scene around the arts lab seems, in part, to have been sparked by his involvement with Lindsay Kemp’s mime company, taking a role in Kemp’s Perriot In Turquoise and "living with this sort of rancid, Cocteau-ish theatre group. . . reading Genet and listening to R&B; the perfect bohemian life". ‘…Dazed’ revels in precisely that squalid glamour and rejection of sexual norms, and forges the link between Kemp’s camp boho clique and what was to become Glam – not so much free love as omnivorous lust ("It must strain you to look down so far from your father’s house / And I know what a louse like me in his house could do for you").

Bowie was also heavily under the spell of the Velvet Underground, and while ‘. . . Dazed’ comes nowhere near their abrasive churn, its rattles and bangs are closer to that than the rest of the album’s melodic feyness. Lyrically, the song is less a stream-of-consciousness than it is a violent vomiting of disjointed imagery – a "head full of murders" that are part of a "brainstorm" occurring "about twelve times a day".

Sanity and it’s fragility were to later become major themes for Bowie, in particular the idea that madness has a seductive pull, a notion he was to explore conceptually on The Man Who Sold The World and in actuality during his notoriously cocaine-addled mid 70s period. Here, he goes as far as to present his narrator’s derangement as sexual peacock display to the previously indifferent "pretty girl" of the song’s intro ("You could spend the morning talking with me quite amazed"). There is also a foreshadowing of the dissolute messiah figures of Ziggy and the Thin White Duke, in the claim to be "the cream of the great utopia dream".

The final verse’s brief reference to "the Braque on the wall" is one of Bowie’s at-first-glance pretentious but actually rather apposite allusions. Georges Braque was a peer of Picasso in the early Cubist movement, creating images that collapsed all the faces of three dimensional objects into a single, simultaneously viewable flat plane. As a statement of intent, it vividly presages the playful identity juggling that Bowie adopted in the early stages of his Glam phase as a positive means of engaging with the world. "It’s very catching", he sings with an audible chuckle.

Where the album stands apart from the rest of Bowie’s work is in the intimate and confessional nature of much of the lyric writing. ‘Letter To Hermione’ is as the title states, a direct plea to his recent ex, dancer Hermione Farthingale, with whom he’d performed in the (mercifully forgotten) folk trio Feathers. ‘Janine’ is reputedly about a friend’s girlfriend, in which Bowie somewhat waspishly details what he sees as the titular anti-heroine’s many faults, a woman who "scares me into gloom" and is "too intense". Bowie was never really to revisit this kind of territory, preferring henceforth to plumb deeper psychological territory by writing from within character. As it is, these two songs (and the less successful ‘An Occasional Dream’) are the last hints of a possible career as a conventional singer-songwriter, writing fairly straightforwardly about romantic relationships.

Similarly, the well-crafted lyric of ‘God Knows I’m Good’ is an impressive but slightly self-conscious stab at being an English Dylan, with its third person account of an impoverished old woman shoplifting for food, and investigation of the psychic cruelty of Catholic guilt. There’s nothing wrong with this stuff, but it’s pretty ordinary, acoustic guitar strum-along fare, as Bowie goes.

As usual with such packages, the second disc of out-takes and rarities somewhat underwhelms. The only really essential tracks are the two halves (split into the A and B sides of a flop single) of a re-recorded proto-glam version of ‘Memory of a Free Festival’, featuring Mick Ronson and Woody Woodmansey (essentially the first group recording of the band that would become Ziggy’s Spiders From Mars).

After that, it’s a bit of a barrel-scrape. There are two versions of ‘Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud’, two of old Deram out-take ‘London Bye Ta Ta’, yet another ‘Memory of a Free Festival’ and a downright bizarre Italian language version of ‘. . . Oddity’ called ‘Ragazza Solo, Ragazza Sola’ (‘Lonely Boy, Lonely Girl’), whose trite lyrics bear absolutely no relation to the original. If it’s all free, you might as well have it, one supposes, but it does all feel somewhat superfluous. Furthermore, seasoned Bowie-philes will arch an eyebrow at the claim that much of this material is “previously unreleased”.

Ultimately, Space Oddity‘s lack of coherence is its undoing; as Bowie himself told Radio 2 in 2000, "It never really had a direction". Given that Bowie’s albums from this point on up to 1980’s Scary Monsters would increasingly boast an almost novelistic degree of conceptual and musical focus, it doesn’t seriously hold it’s own in their company. However, it captures its creator at a fascinating crossroads, and is much more than a fans-only curio.