Visit the Stack Magazines website

This interview with Fever Ray is taken from Plan B magazine, this month’s Stack selection.

Words: Lauren Strain

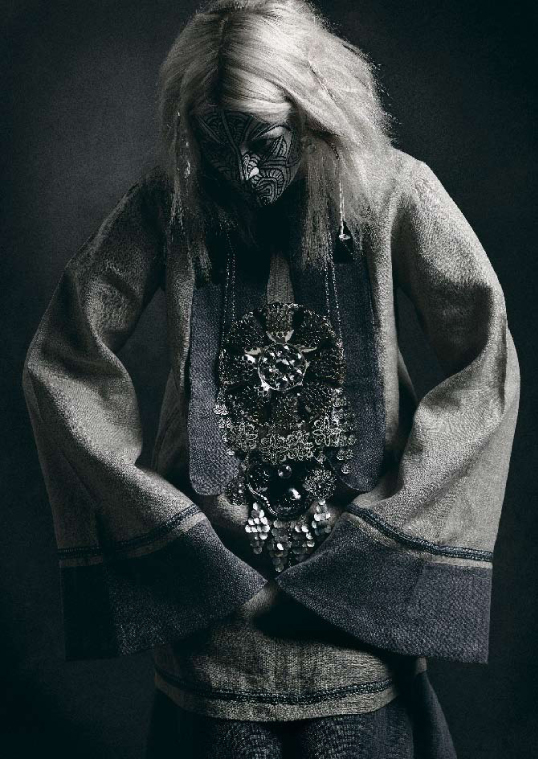

Photograph: Johan Renck

A camera trolls the room. A body lies bent on the carpet, face turned away. Clothed corpses dot the bottom of an empty swimming pool. A fish-headed figure stands unmoving in a stairwell, feathers sprouting from its neck; behind, the wall is studded with trophy animals, antlers casting shadows onto sickly white paint. An ownerless alsation that appears from nowhere, walking past the piano. Candles burn. I keep returning to the pool, pocked with bodies. There are signs of conflict; chairs overturned. What has happened to these people?

The video to ‘If I Had A Heart’, the first single by Fever Ray – aka Karin Dreijir Andersson, one half of brother-sister duo The Knife – is no typical music video, but then, this is the work of Andreas Nilsson, a Swedish visual artist and director whose longlasting affinity with The Knife has borne a number of astounding short films, culminating in his bombastic, haunted scenography for the band’s Silent Shout tour in 2006; a backdrop that more suggested a piece of drama than a concert. Indeed, the video seems to possess certain qualities of atavistic theatre; there’s something ritualistic about it, something ceremonial, or sacrificial.

"Andreas was very much into this idea of ritual," Karin insists, calling from home in Stockholm. "He wanted to have – " she pauses to giggle, separating each syllable delectably, "ec-to-plas-ma! He wanted to have this image of something having been driven out of the person with ectoplasma. We have quite a big death or black metal scene in Sweden, which is very interesting to me because they take very good care of the visual aspect of the music. Andreas leaves the film very open to interpretation; I think it is very important that you can make your own conclusions about what is going on in that place."

The sinister is innate in Karin’s music. Fans of The Knife will immediately recognise that almost _un_recogniseable vocal. Pitchshifted, filtered and encoded, it is neither female nor male, human nor android; it often appears to be not one voice, but

several, exhumed, each with their own encrypted, abstract command: "Come here, sparrow," beckons one, "Watch my hand/Black and blue seeds…" It halts, unfinished. "Do my hair, paint eyelash/ Reappear in a flash," counters a mirrored face, blinking. Blocks of synth, clean as needles, tessellate and repel like appearing/vanishing steps; the melody ascends and plunges accordingly, running

and falling and starting all over again. Clammy beats play out like the snap of clavicles. Part of us wants to escape this labyrinth of cold pipe-clangs and jewelled, ominous stares – but the very fact of its darkness is what draws us further into its centre.

The idea that we’re continuously attracted to things that may ultimately harm us seems to inform Karin’s work; when I ask why, for example, she enjoys manipulating her voice into something indeterminate, even genderless, she admits that there’s a satisfaction to be had in evading our certainty, in causing us discomfort. "This idea of gender perspective is very interesting," she explains, "because you always want to know whether it is a female or male vocal, and you do not find out." So do we listen to a message from an ‘artificial’ voice more deeply, because we do not know what – or who – it is?

"An artificial voice can definitely sound more real, I think. In music, you work so much with emotion and in, like, trying to – how do you say it – tell about emotions or atmospheres or environments. So it is therefore interesting to work with the voice in the same way that you would work with an instrument. The most important thing is that I just want the song’s expression to be the best one, and it often feels like I should pitch the voice in some almost unnatural way to achieve that."

I return to the video for ‘If I Had A Heart’, where Karin appears only once, her face concealed, daubed white and black in the pattern of a skull, eyeless. In performances, photoshoots, interviews, The Knife would wear black masks with foot-long beaks that protruded where noses should be, themselves like blades, serrated and brutal-looking. They erased any sense of Olaf and Karin as humans; they were creatures, about which everything was unknown. They could’ve been stalkers. They could’ve been attackers. But the intention, probably, was for them to be vessels; faceless, so that they did not project onto the music any determinate identity.

"If you’re really interested in music, you don’t mind who is on stage or what they look like," reasons Karin. "When you talk to people who are not so into music, who are maybe more into fashion or – I mean – how things look, it’s like they think that music

composers should be… celebrities, or something? Personalities. That’s when there’s this confusion. We work with the stage almost in the same way you do with theatre – you try to locate the visual expression that maximises the sound, rather than anything that reveals the people behind it."

Andersson is rehearsing for her solo tour, which will transplant the cold, viscous gel of her album to the stage; she’ll be alone, brother Olaf busied with the music and libretti they’re writing together for an opera conceived by the Danish performance troupe,

Hotel Pro Forma, and inspired by Charles Darwin’s Origin Of The Species. "It is not about Charles Darwin, really," she emphasises, "but around him. Pro Forma are known for their very beautiful performances with film, visuals and music… it is some kind of stage art."

Having worked so intensely as a duo for so long, it must be invigorating to work closely with such a large group, I venture. "Actually, they want everybody to work separately!" she exclaims. "Us and the choreographer… we don’t meet. They think everything should be very separate before the premiere, and then in the last month they put it all together somehow! But that is good, you just focus on what you want to do and don’t compromise."

Such isolation features heavily in Karin’s music; Fever Ray is full of ghosts, doppelgangers and shadows, but none seem more real than Karin, alone, singing into a resounding panorama of electronics. "In the beginning, it was a little strange," she remembers. "Olaf moved to Berlin when we finished Silent Shout and he almost took the whole studio with him! So I had to start with practical things, which was quite good for me because I had to get into the more technical side of the studio work which I had relied on Olaf to do before. It was not a nice place, really," she says of the studio; "it was down in a basement, a little room south of Stockholm. But really, I was looking for a place that wasn’t very nice, where I could be on my own."

I can’t help but wonder how the need for solitude chimes with Karin’s role as the mother of two young children. Has she found it difficult to work, artistically, since they were born, and did she feel it was imperative that she must continue to create, even if it were problematic to do so? "It is probably the biggest change in life that you can experience, after you have moved from home,"

Karin begins, her voice kindling with affection. "It changes your perspective on everything, and it’s the first time that you don’t – you can’t – just think about yourself anymore. But it makes it even more important for me to continue with the music; I think that it’s some kind of responsibility. Making music is a very good job to have when you’re a mother, because when you go home it’s very hectic. Everybody is screaming and there is a lot of people running around. Then, you go to work, and you can relax!" she chuckles.

"It is a fantastic thing to just use music as a way of communicating and learning," she continues. "I love watching kids when they’re all clapping and singing along, and all the… joy… about it. This is something you can forget when you get older, that

music is something to feel good about. But now," she hiccups, drifting into her soft, kind laugh once more, "I realise I haven’t really made a feel-good album! Oh dear."