In retrospect Patti Smith’s decision to spend the eighties bringing up a family was a masterstroke. For a start, after dealing with the music industry on a daily basis, dealing with kids is nothing. No recordings captured in squeaky clean primitive digital quality blemish her CV. (If anything People Have The Power sounds all the better for its Springsteen-esque arm punchiness- no wonder he covered it). Her sensible sabbatical made her officially a legend and beyond criticism, meaning she can’t be blamed for Razorlight, despite Sting Borrell’s shameless thieving of her original style. (He can and will be though, for as long as he steals God’s good oxygen.) Instead reality beckoned. By the nineties friends and family were dropping around her; brother Todd, once glassed by Sid Vicious; her spouse, the great Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith; Richard Sohl, the unfortunately named pianist in the original Patti Smith Group; and most famously photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Once her roommate, Mapplethorpe’s striking snaps of Smith had created an enduring rock aesthetic long before his forays into more controversial fields.

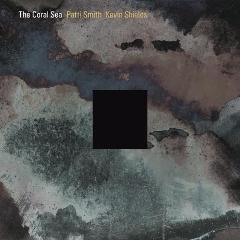

The Coral Sea is a long poetic work originally published in 1996, as Smith tried to make sense of her losses. It describes a mythical trip to the South Seas taken by a dying Mapplethorpe (the HIV stricken snapper lingered, unlike her husband, who was felled by a sudden heart attack). Reluctant to perform it alone, she enlisted Kevin Shields to provide the music for her 2005 reading at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on London’s South Bank.

At the time, the critical reception was overwhelmingly positive. Yet separated from a live context its appeal is less obvious. As the boat heads out, casual listeners might find themselves wondering when the big ape appears (well, I did). Shields generates ambient washes of sound, often unusually intelligible. Yet his playing is easily recognisable, although the two recordings here, from June 2005 and September 2006, are entirely different (the later show is much deeper, laden with effects and far more powerful, probably for being the second night of a run). As an accompanist he is unexpectedly brilliant, adapting but not diluting his own style for the requirements of Smith’s almost casually rhythmic prose poetry.

Eventually a noise battle breaks out between them, which Shields wins. It is gruelling, almost memorable and possibly brilliant. But if you’ve ever fallen asleep at the theatre, this is not for you. It’s not so much a question of ‘you had to be there’ as ‘you had to know him’. Who would have expected Smith to become respectable as a nun while Mapplethorpe remains marginalised?