"I don’t care whether it’s comfortable to listen to," says Jeff Mills of his compelling yet brutally linear strain of techno. Born in Detroit, a former member of the Underground Resistance collective, Mills was set on his creative path following an epiphany at a science fiction festival during the riots that tore apart his home city in the late 1960s. A drummer by musical origin, he first made his mark as a DJ, where among his inspirations were the robo-tendencies of late 70s/early 80s music by Kraftwerk, Gary Numan and Visage. Prior to that he had been a drummer, and he brought to his DJing a technical intricacy and sensibility which he has maintained, both live on the decks (usually three in number) and on his numerous releases, which have come out on his own Axis label, launched in 1992.

Although he eschews lyrics or vocals as such, Mills regards his music as conceptually driven and deplores both the commercial imperative and the perception of DJs as functionaries whose job it is to provide a battery of rhythms for partygoers. "We don’t win awards. We don’t get considered for higher levels of music application. We’re considered to be operating at a low level," he says.

He has sought to counter this impression by, for example, performing and arranging pieces of his such as ‘Bells’ for full classical orchestra, in which context they work surprisingly well – the more so because even by the standards of minimal techno, Mills’s pieces are full-on and unremitting. Despite space and the cosmos providing a backdrop to his work, it is rarely ambient or tranquil a la The Orb or Tangerine Dream but choc-a-bloc with hurtling, piledriving rhythms, a high bpm laser attack, all of which reflect Mills’s conviction that, in the coming decades, mankind may find itself engaged with outer space in ways currently only dreamt of in science fiction.

To further realise his conceptual ambitions, and to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Axis Records – in the wake of whose vapour trails so much modern electronic dance music has developed and flourished – Mills publishes a book, Sequence, in October. It comprises photos, designs and artwork which visually celebrate and reflect some of the key themes and ideas in Mills’s music (in which spirals, for example, figure as a recurring motif). It also contains a selection of some of Mills’s choicest cuts from this period, accompanied by notes from their creator telling their back story, from 1993’s ‘Automatic’ through to ‘The Industry Of Dreams’, all of which reflect his unswerving consistency of purpose and refusal to pander to the wants of the dancefloor crowd – which, paradoxically, account for his ability to pack floors.

Mills had flown into London to take part in Bloc 2012, only to discover that his services would not be required following that festival’s cancellation. All of this meant that The Quietus was granted more time than expected to chew the fat with the soft-spoken but outspoken, dapper techno legend in the lobby of a central London hotel.

So, er, no Bloc Party. Has anything like this ever happened to you before?

Jeff Mills: It’s not that normal, something like this. I’ve never had an event cancelled for health and safety. I wondered if maybe it’s a tense time with the Olympics coming up, no one wants to take any chances. I’m imagining there’s a lawsuit in there somewhere.

You’ve been talking about the idea of publishing this book for a few years now – as far back as 2009. It certainly feels extremely well-produced, gallery-worthy.

JM: We’ve been through a couple different scenarios of how the book should be. I started kicking around the idea about four years ago. We finally arrived at a plan: what I thought would be most interesting is a book mainly about design, about the methods we use to realise each project – the behind-the-scenes thinking, things we wanted to do, the machine of electronic music, of what it can produce other than what you see at parties. It shows a lot about the type of things I think we should see more of from electronic music, given that it’s 2012, it’s been around for over 25 years – ways the genre has splintered off, the things it ought to be doing. It focuses on music but in a more conceptual way – the stories behind the tracks, which is also rare in this genre. It helps the listener decipher what they’re listening to, gives the chance to ponder it. In this industry, too much music goes in one ear and out the other.

You’re not exactly a peripheral figure in the dance scene but you do often seem to be at odds with the industry.

JM: There’s never been that much interest in the idea of an album being about something. Increasingly, the pressure was to find a track that people could dance to and go crazy. And now there’s software to do that for you, you know what’s coming. That’s the majority of the industry right now. This DJ, Ibiza, you know what’s coming. It’s a pencil factory. For a lot of people that means security, that means I can have some stability in this unstable industry – it’ll get bought.

Surely, with a mode of music that’s as obviously reactive as dance music, the temptation to please the crowd must be enormous.

JM: But the idea of people deciding whether they like it or not gets in the way of music being a way of developing musical creativity. Making them happy denies that. I eventually decided they had to be taken out of the equation. The music is for them but your intention should not to be loved by the crowd and to make lots of money. There are consequences to not acknowledging the people – I’ve had money problems in the past because the records didn’t sell. If I think about what the people are thinking about, I wouldn’t be able to DJ, I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night. I leave that for other DJs, other producers. I need to find ways [to exapress] about what I feel about tomorrow.

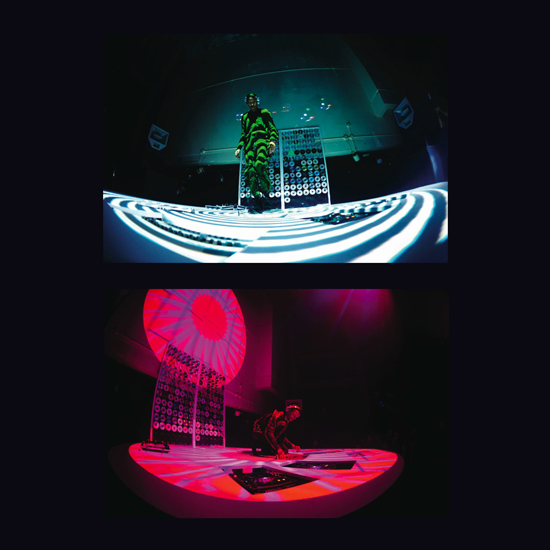

Photo from Sequence book

"Tomorrow" isn’t a preoccupation in dance music though, strangely, despite its futurism – like a lot of pop audiences, they can be desperately conservative by and large, fixated either on the here and now or on yesteryear. Tomorrow can be as frightening a prospect as Monday morning.

JM: And so you have this constant shuffle of people trying to find stability and security – on Monday you may be a famous DJ, by Friday it may be someone else. I always felt that if the economics of it could be taken away, the audience factor reduced, and just focus on making music, perhaps things would be closer to who you are as an artist, what your capabilities are. Better that than me always doing something because I know it always works.

How did you make the transition from radio DJ to musician?

JM: There’s a difference between those DJs who wanted to be musicians and those who wanted to DJ because they wanted to be DJs. I started as a musician – these were the early days of hip-hop. I was in a couple of bands – it was that summer when hip-hop culture had really hit. Every kid in my neighbourhood wanted to be a DJ, so I wanted to be a DJ too. I found it, if anything, easier to manipulate turntables than to play drums.

But I always approached DJing as a musician – using all the buttons, all the pieces of the equipment to enhance the sound. I don’t get so excited about the perfect mix. I’ve been DJing forever but I never thought I really approached it like a DJ. I went to clubs and partied when I was young but I was always into the music rather than the culture. I wasn’t into "clubbing". I don’t care for equipment for its own sake. I’d rather go to a museum, read a book, watch TV, than just play a keyboard.

Picture from Sequence book

Despite the sci-fi preoccupations in your music it never sounds cosmic or remote or out there, but a bit like the Big Bang happening right in your face.

JM: I think it’s that way because that is the reality of space. It’s dangerous. It’s lethal. The sun is lethal. It’s the sound of imagining human beings coming face to face with these extreme forces. It’s frightening. It’s not easy. It’s not pleasant. Maybe the safest place for us to be is down here.

Astronauts live in constant fear of death. It’s always on their minds. I had a meeting with a Japanese astronaut. He went on the Endeavour and various missions. We talked about space – he told me that the whole thing is terrifying. There isn’t one moment when you’re not thinking about what is on the other side of that craft. Your every moment is being monitored by NASA, they control everything about your existence, right down to your breathing. When I’m composing, and I’m imagining a crater on the other side of the moon, I’m thinking of a human being staring into a bottomless pit the size of London. So what I’m thinking of is that maybe within our lifetime, we may experience competely different atmospheres, new locations.

I was never convinced that all music should be pleasant. I tend to believe that it’s more of an extension of one’s voice, and sometimes what one has to say is not pleasant. I know that a lot of music I make doesn’t make sense now because the world is different now. But future will be a very different situation. It’s our nature to think about preparing for tomorrow. And a large part of that is trying to find another place for us to exist – for us to have water, liveable atmosphere. This isn’t science fiction, it’s science. We may come to a point where life on this earth is unliveable and we have to find new ways. Just the idea of surviving may well be the largest part of a human’s life in the future. Not shopping, working – just surviving. So a lot of the drama, the suspense, the aggressiveness in the music is conditioning the listener for this. And learning how to listen is a part of that.

I understand that when you were six or seven, during the time of the riots in Detroit, your parents took you and the family out of the city, drove up to Montreal, where you saw an EXPO festival. Might this have created a connection in your mind between strife in the present time and futurism?

JM: I always thought that maybe played a role. I remember it was just too dangerous to be in Detroit – we lived just a few blocks from the worst part of the rioting – so my parents decided to drive us out to Montreal, along with some other families. It was a different world – everything was more colourful. Not quite Disneyland, but different, exotic. I was four or five at the time. It convinced me that there is this… I don’t want to say ‘escape’, but the idea that you can turn your attention and see far beyond what’s happening here, and calculate that when it’s all over, what are people going to be thinking of, how the future will pan out. So when I was DJing I was always thinking beyond – what people would want after Chicago House?

I’ve always had a theory that a lot of black or African-Americanism tends to be futuristic because the past. The 50s, the 60s so fondly and nostalgically remembered by white audiences – holds no pleasant associations for black people. The future has at least the potential to be a better place, hence the innovative drive and love of electronics in so much popular black music from techno to drum & bass…

JM: I dropped most of my impressions of the differences between black and white some time ago. People are people, there are good people and bad people, good people who do bad things and vice versa and that’s about it. There isn’t particularly one way to be. Looking beyond race, I think we’ll have a situation where the difference will be between keeping people back or allowing them to expand. And this will have nothing to do with economics or where they live but their capacity to overcome fear. I think race is not as important as we make it out to be.

And it’s going to be even more different in the future. We’re becoming more able to communicate with people completely off the radar [via the internet]. And that’s the reality of where we are. So the idea of being proud of being from a certain place or ethnic group will become part of the past, a ball and chain if anything. But then, some people feel more comfortable with that, saying that they’re from Detroit and feeling that they’re part of the Detroit techno legacy.

I think that people have been ready for quite some time to move on from this. The 60s, with flower power and the hippy movement, might have been the closest point I think humanity has ever reached in terms of leaving behind racial barriers. I think we have all been ready for quite some time. But somehow we’re constantly being pulled back. I’ve read a lot from how people were feeling and thinking in the 60s. It was a turbulent time, but there was a reason for that – peoples’ ideologies were clashing. I think we’ll get there again and take lessons from the past and eventually reach it. I’d figure about 2060, 2067. About the Age of Aquarius. Every 30 years there seems to be more backlash against the status quo than in other decades.

You think about future decades? I never think about future decades. I never gave 2012 a single thought until it arrived, certainly not 30 years ago.

JM: Wow. Really?

I suspect you’re exceptional in that respect. The future is unreal to most people.

JM: We have to think of it more and more. We need to think further and further ahead to prepare ourself more. I think something’s going to happen that’s going to make us put all our priorities in place. I have no idea what it could be, but I sense something will happen that will bring us back down to earth again, think about what’s the most important thing. And I just want to help people to be mentally prepared for that.

The biggest threat is something we will have no control over. There is a fragile line we all walk on, and if music can make walking that line make more sense and you know what the next few steps may entail, then you will have a little more idea about what will be at the end of that line, then it’s all worth it: travelling around the music, playing music for people every night, making music that terrifies the listeners, spending hours making sure a track is just correct.