When I pitched the story about Johnny Vana & The Big Band Alumni to The Quietus editor John Doran, I blithely assured him that the players had more than 700 years combined experience.

Well, I lied.

Because it turns out that these 17 cool cats have been playing music for an astounding 1300 years, give or take a decade. Which isn’t really surprising since they are the survivors of the most popular American Big Bands of the 30s, 40s, and 50s.

We’re talking Glenn Miller, Frank Sinatra, Woody Herman, Harry James, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Les Brown, Sammy Kaye, Lawrence Welk, Stan Kenton, Nat “King” Cole, and Spike Jones.

How big were they?

Huge.

The Big Bands were the Beatles, Stones, and U2 of their day, during the period of 1933 to 1948. It was a tumultuous time that included the end of Prohibition, The Great Depression, and World War II. And Big Band music was the heartbeat of America.

Decades before Beatlemania, the Big Bands were all the rage with their hot, sweet, swinging grooves. Their popularity coincided with the exploding popularity of radio that played their records and broadcast their shows live from the hottest ballrooms in America.

Goodman, Dorsey, James? Except to jazz fans, these names mean next to nothing now. But before rock & roll, Swing was King on the Pop charts, and these bands were the swingin’ elite.

And now, more than seven decades later, a dwindling but vibrant group of the original Big Band musicians gather to blow their trombones, clarinets, and other instruments nobody in today’s popular music even cares about anymore.

It happens every Tuesday morning 10:30 sharp at Las Hadas Mexican Restaurant, a cavernous place in a sun-bleached suburb of Los Angeles, and a far cry from the huge venues like Roseland and The Hollywood Palladium where they once held court.

Talk about a time warp.

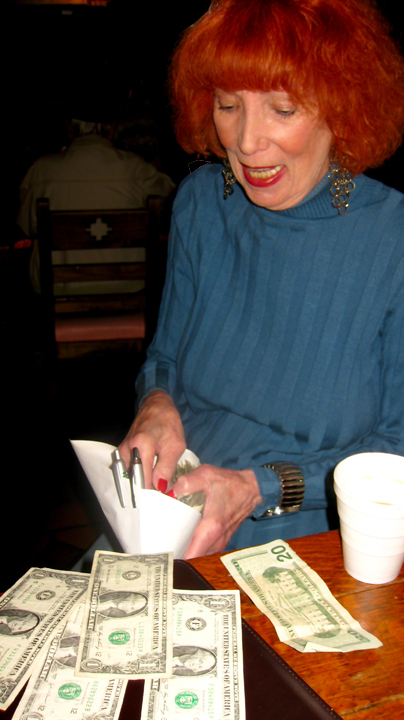

A little sign says “$6 donation for dancing and listening.” Trying to crack wise, I ask the flaming-haired 80-year-old ticket taker “How much if I dance without listening?” But she has my number, and then some: “Honey, for all I care, you can stand on your head. It’s still 6 bucks.”

By 11 a.m. the joint is jumping. I find a place to hang out at the bar, and Johnny and the boys ease into ‘String of Pearls’, a #1 hit instrumental for Glenn Miller in 1942.

For those who have forgotten, never knew, or never cared, the standard Big Band line-up is five saxophones, four trumpets, four trombones, and a rhythm section of drums, bass, piano and guitar, plus a girl or boy vocalist.

As the smooth but driving rhythms cascade from the bandstand, the dance floor quickly fills up.

And then… Wait a minute! An elderly man seems to be having a seizure. I’m about to call 911 until I realize that he’s not in medical distress, just doing some senior citizen jitterbugging. And the woman I thought was helping him off the floor is actually his dance partner.

A tanned 85 year-old gentleman named Jack Lloyd is the Band Boy a.k.a. the manager. I mention that I’ve seen The Alums three times and never once heard anyone play a clam. “And you never will, not in this band,” he rumbles with good-humored gruffness.

Jack Lloyd and Kit Smythe

A sloe-eyed temptress of a certain age sashays up and eyeballs the both of us. There’s a very pregnant pause. “So what do you do?” I ask to break the ice. “I do” she says with a wink, ”the guys in the Band.”

Bingo. It’s like being in a 40s movie with the original cast, only 70 years later. People are flirting, zinging one-liners, and partying like it’s 1944. If you think most senior citizens are this bubbly, you haven’t been around that many old people.

But it’s not just the crowd that’s lively.

Take the ascetic but friendly gent who has just celebrated his 90th birthday. Ethmer Roten plays clarinet, alto sax, flute, and the occasional piccolo for the Vana Alums.

Roten’s credits span a good chunk of American culture of the last 70 years, not just records but film, too. He played on everything Henry Mancini recorded. He accompanied top stars like Frank Sinatra, Nat “King” Cole, Andy Williams, Lena Horne, Judy Garland, Liza Minnelli, Mel Torme’, Debbie Reynolds, John Raitt, Perry Como, Nancy Wilson, Ella Fitzgerald, Nelson Eddy, and Bernadette Peters.

Roten started out playing sax and clarinet in Jimmy Greer’s band right after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. But after a couple of years, the six-show-a-week grind got old, and he’d had enough of the road. Besides he wanted to stay close to another kind of action: Hollywood. Skilled and versatile enough to land a chair in the Universal Studios orchestra, Roten was a “first call” session player for four decades, and his flute, alto sax, piccolo and clarinet can be heard in 650 major flicks like Dr. Zhivago, Days Of Wine and Roses, To Kill A Mockingbird, Funny Girl, and How The West Was Won.

Like all of the guys in the Alumni Band, he’s not in it for the money. “I just love playing with these guys. We’re the last of the Mohicans,” he says, “and we’re trying to protect the sound by playing this music as it’s supposed to be played. I only get $22 and change to play with Johnny, but thanks to a $1,800 a month supplement from the Musicians Union, I’m doing all right.”

When I ask the glowingly fit nonagenarian the secret behind his vitality, Roten smiles “Clean living, a wife that can cook, and the fact that I’ve always taught, tutored and mentored scores of up and comers, of which Tom Scott is probably the most famous.”

Ethmer Roten and friend

A few chairs down from Ethmer Roten, in the front row of the bandstand, sits a genuine character (in the best sense of the word) named Dave Pell.

In addition to being a stellar sideman, Pell, an extremely with-it 87 year-old, also made his mark as bona fide jazz artist in his own right.

He started out as a teenager, joining Tony Pastor’s band in 1944, then spent a couple of years with Bob Crosby’s Bearcats. Then out of the blue in 1947, legendary bandleader Les Brown called him.

“Les heard I was good,” Pell laughs, “though he had never actually heard me play himself. His sax player had gotten thrown in jail for drugs, and they needed another tenor sax right away. So he calls me one Friday morning and said ‘be at the Trianon at eight and bring a pair of dark pants. We’ll give you a jacket.’

That’s how I got into the Band of Renown.”

“When I came to California, I made friends with the guys at the Hollywood Palladium, and got into the relief band. We played when the headliners took a break. That was a helluva band, including Stan Getz, Nat “King” Cole, and me. Stan was very nervous then. He sounded great in the dressing room, but get him in front of people and he got stage fright and played like crap. It took him years to overcome it. Me, I never had stage fright because I didn’t give a shit. I could do endless one-nighters and play the same solo over and over, I was good at it. I had chops, and I was a mimic. I could sound like anybody; hell I could even be comedic. Gradually, I developed my own recognizable style.

Around 1953, Pell could see the handwriting on the wall for the Big Bands: “It was getting old, fast.”

So he formed his own group, the Dave Pell Octet, along with trumpeter Don Fagerquist. With arrangements by aces like Marty Paich, Shorty Rogers, and Bill Holman, the tight ensemble invented a lighter style that came to be known as West Coast jazz, featuring an amped electric guitar playing notes usually played by a horn. Some critics panned the Octet as middlebrow jazz, but the ever-plain-spoken Pell referred to it as “mortgage paying jazz.”

Over the years, Pell recorded 32 albums for Atlantic, Kapp, Coral, Capitol, RCA, and his own PRI imprint. I ask him if he was ever on Blue Note. “Nah,” he answers “but I bought the Blue Note label when I was at Liberty.”

As the market for live jazz waned, Pell began to do a ton of session work. He worked with Henry Mancini, and played on the Rock Around The Clock soundtrack. For Billy Wilder’s classic film Some Like It Hot, he produced the all-girl band and played the sax parts for Tony Curtis. “Curtis was a perfectionist. He didn’t want to look like a schmuck in the movie, so he made me teach him the correct fingering for the notes he was supposed to be blowing.”

“Then in the 60s, I pretty much quit playing,“ Pell says, “I got into the record business and produced about 400 LPs, everything from jazz (Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald) and pop (Timi Yuro, Vicki Carr) to early rock and roll (Bobby Vee, Gary Louis & the Playboys).”

“I produced Sinatra, who, by the way, you could only get one take, maybe two, out of in the studio. On Frank’s version of ‘(I Left My Heart in) San Francisco’, we did 100 edits on his two vocal takes. It was a real pain in the ass. Like a lot of production, it’s more fun talking about it than doing it.”

Not everybody makes the transition from sax man to record man, but Pell flourished. From the mid 60s to early 70s, he was head of music and A&R at Liberty Records overseeing nine different staff producers. Then he had top posts at United Artists and Uni, hot labels at the time.

When Motown moved to L.A. in mid 70s, they created a new label called Mowest. Pell ran the label, was head of A & R, and helped evolve the Motown Sound into 70s soul and disco by signing Lionel Ritchie and the Commodores.

I suggest that his salty tales of the music business would make him a perfect guest lecturer at college campuses, but he nixes the concept: “Listen, I got two Chihuahuas who depend on me and I spent three days in Pennsylvania honouring Les Brown… I’m just glad to be back home. For me, this band is a good situation: when I started playing with them about 15 years ago, I hadn’t played in 25, but I still have a semblance of what I used to be able to do. You never retire.”

“And this place kills me,” he says referring to Las Hadas. “These people are here before 10 every Tuesday morning, all dressed up and raring to go.”

Johnny Vana and Dave Pell

He’s right. These elderly hep cats are positively throbbing with life. The ladies are bejeweled, fully made-up, their motors running hot. The courtly gents squiring them to the dance floor may have lost a step or two, but they can still cut a rug.

And it is nearly impossible to keep still when the band launches into ‘Sing Sing Sing’, the ‘I Gotta Feeling’ of its time.

The silver-haired Vana pounds out the primal tom-tom intro that Gene Krupa made famous, then the trombone and sax sections join the ruckus, setting up a gangbuster brace of brash horns and whoosh, they’re off to the races. A seven-minute juggernaut of old school high-energy swing that’s as hot as anything you’ve ever heard in your life.

Johnny Vana takes a cocktail break

When the band takes a break, I sidle up to Johnny Vana and get an earful about his colorful past.

At 75, Vana is one of the youngsters, but he’s still got over 70 years of experience since he started drumming at the tender age of 2.

“I was a prodigy,” he begins, “Won my first competition at 2 ½, sat in with Glenn Miller at 4, won Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour, then joined the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra at 14.” He went on to play with bands including Harry James, Sammy Kaye, and Les Elgart. He backed artists like Peggy Lee, The Ink Spots, George Burns, Jerry Lewis, and Bette Midler. He also found time to work at Capitol Records in A&R, and to lecture at colleges like the University of Texas.

The original Alumni Association was formed in 1999 by trombonist George Kenney (Sammy Kaye) and vocalist Randy Van Horne (The Encores, Esquivel). With a lineup of Big Band alums and studio session players, they played regularly at Leon’s Steakhouse in Burbank.

After a few years, there was grumbling among the players about the band’s song selection. The issue being that Van Horne was calling too many of the songs he wrote, and not including enough standards.

Eventually the two founders ankled the group, and Vana (assisted by manager Lloyd) became the leader in 2005.

So why, I ask Vana, has Big Band music lasted so long? “Because it’s Dance music, it’s Pop music, and it’s Jazz. There’s a little bit of something for everyone. And when they play the music not just the notes, that’s when it swings.”

That makes perfect sense when you think about it. Any competent musician can play notes, but not every musician can swing. (Musicians like Charlie Watts, are the exception rather than the rule for example.)

Sadly, authentic 40s Swing seems destined to become a lost art.

No matter how good of shape the Alumni Band is in now, they don’t have all that much more time left on the planet. And once these originals are gone, where are you going to find drummers who’ve grown up with rock and hip-hop but still want to play music that’s 80 years old? And where, except in the military or prison, are you going to find four trombonists who’ve played together for decades?

One guy who’s going the extra mile (and then some) to preserve the genre is Bruce Bisenz, a lanky, dark-haired fellow with a tidy beard who looks younger than his 70 years.

A retired TV sound mixer, Bisenz sets up the mics and P.A. for every gig, records them into a laptop ProTools rig for later mixing, and then breaks it all down.

“Every gig takes me three and a half hours. That’s about twice as long as the band plays, which is about 100 minutes. Never get a penny, not even expenses. So why do I do it? I see myself as a steward for Big Band music. My contribution is to record the live experience of this classic music with modern equipment. Put these guys in a studio and they tend to play it a little safe. But here at Las Hadas things get wild, and for me, that’s what it’s all about.’

And just maybe it is all about the music. And if it can make folks in their 80s act like they’re in their 20s again, count me in. Maybe old age really is a state of mind, or as Jack Lloyd puts it: “It’s alright getting older, it’s not okay to get old.”

On one of the days I’m at Las Hadas, a group of teenage musicians from a local high school have come to hear the band.

There are about 30 of them, and at first they huddle in the back of the restaurant.

After a few numbers, their shyness evaporates and they move in closer, drawn by the music, until they’re sitting right near the stage, watching how the old pros’ finger their axes, and sneaking a peek at a stack of arrangements that’s thicker than the L.A. phonebook.

I talk to a couple of fresh-faced Hispanic kids, a boy and a girl. They’re forming a Big Band at school, and they’re jazzed to be the first members.

So maybe there’s hope for Big Bands yet.

“There are always a few youngsters in the crowd.” says Johnny Vana with a twinkle in his eye, “Sometimes they ask if we know any rap songs. I tell ‘em sure, what do you want to hear? ‘Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams’ or ‘Rhapsody in Blue’?”