Remember when the utopian images of the digital world projected by corporate interests seemed almost convincing? When swifter net access was heralded by the friendly AOL lady, whose taut frame would lead the children by the hand into the computer room, where they’d be dazzled by the delights that lay within the little white box? Where terms like ‘surfing the net’ and ‘information superhighway’ were still thrown around naively, suggesting it was perfectly plausible just to get your feet wet while glibly sliding across the surface of the data sea – without fear of getting snagged on seaweed, eviscerated by a shark or simply plunging headlong into its murky depths?

Laurel Halo does. Her music to date has addressed these beautiful notions of unlimited learning, no-strings online fun and freedom of communication. But it’s placed them in the context of their darker flipsides, which have become particularly apparent since the advent of social networking. The push-pull between these two extremes crystallised as a deadly techno undertow beneath the surface glow of last year’s Hour Logic EP. It even went as far as its track titles, which reflected time distortion and web-surfers’ apparently contradictory experiences of speed and stasis. On the whole, though, it offered a romantic perspective on co-existence with modern technology. Somewhere just out of sight the AOL lady sat bloated in her bedroom and bleeding excess code around the edges, umpteen interesting fragments of information lay unabsorbed in web browser tabs, and sinister vested interests sent legal teams burrowing for incriminating information – but they were out of sight, if not wholly out of mind.

Hence Quarantine. Here, Halo’s relationship with modern technology, right down to the instruments and tools with which she makes music, is revealed to be ambiguous at the best of times. At worst their shared space is fraught, anxious, insecure. That tension is present in her lyrics, which present a relationship in the context of communications technology and the art/science interface (see ‘Tumour’s "caught behind a wall of tears / Distorted liquid image of you / The signal keeps cutting out but one thing is clear / Nothing grows in my heart, there is no one here"). But it’s most clearly articulated musically, through the ever-changing relationship between her voice and the synthetic music that surrounds it. Throughout the album’s length – even across a single three-minute track – they flirt with one another, often circling at a comfortable distance but at other times pulling away hard, wrenching outward into uncomfortable dissonances. Occasionally, as on second track ‘Years’, they’ll merge entirely, her voice melding with the machine to form a penetrating sine wave drone. On ‘Carcass’ and ‘Tumour’ she stretches far above her range and her voice audibly cracks, spearing outward to raze the eardrums.

This continual flux plays havoc with the metre of the songs themselves. What’s so shocking and rewarding about Quarantine is that it’s undeniably a pop record, yet it makes no concessions to the listener. The songwriting ease that characterised her debut King Felix has returned in full force here: closer ‘Light + Space’, as the album’s most accessible piece, is sci-fi dream pop, all talk of mountains falling and hive mind; ‘MK Ultra’s is as catchy a chorus as you’re likely to encounter. But they’re no easy listen. Halo has spoken in interviews of intentionally avoiding the use of pitch correction or digital voice enhancement, precisely so that all the textural qualities and slight imperfections of the human voice are laid bare for all to hear. She’s frequently buffeted by the whirl of her surroundings, and misses a note or catches a breath, subverting the accepted pop wisdom of perfect pitch/perfect timing. These songs are uneasy with the digital setting they find themselves within, uneasy in their own skin, even uneasy in their relationships with others: though musically it’s thematically dense, Halo’s lyrical themes here are classic and straightforward enough – loss, isolation and heartbreak.

Surprisingly for an album of songs – all the more seemingly counterintuitive – is that Quarantine is, to all intents and purposes, beatless. Furthering the process Hour Logic hinted at – where techno rhythms were sunk into an electric wash until they became mere grains that crackled weakly from beneath – almost all semblance of rhythm for Halo’s voice to grip onto has been lost. So a second contradictory aspect emerges: is Quarantine an ambient album that battles with its pop impulses, or a pop album that struggles with the softness and uniform density of its surrounds, and caves in upon itself?

It’s impossible to tell, but it’s rare indeed to hear a song-based artist delving deep, as Halo does here, into the Thomas Köner/Porter Ricks/Christian Fennesz school of intricate sound design, careful layering and illusion of infinite depth. The results are nothing short of magnificent, producing a set of tracks whose fizzing surfaces are always disturbed by some new action just beneath, where ridges of static ruffle and tumble over one another, and where harsh regions of higher density sluice violently into the foreground. Mood is determined by topography: when the terrain is rough and craggy, as in many places during the album’s second half, her voice responds in kind, varying in confidence or slipping into the background. Its smoother moments – pulsating opener ‘Airsick’, the hypnagogic vortex of ‘Holoday’ – have a Music For Airports vibe, evoking fast motion, polished surfaces and transit (appropriate – she’s spoken about aeroplanes and recycled air in public spaces as reference points around the album).

A few tracks provoke particularly sharp intakes of breath. ‘Wow’ marks the mid-way point between the lighter songs of the album’s early part and its bleaker (but still better) second half, and does so playfully – Halo stacks interval upon interval until her voice becomes syrup-thick, then blows bubbles with it. ‘Carcass’ coils two muffled bass lines around one another until it’s impossible to distinguish between the two, leaving an implied rhythm to swagger to the surface; two minutes in, Halo’s piercing shrieks are joined by a phantom choir whose strains destabilise the whole track and bear it into the void. The softly struck pianos of ‘Morcom’ are savagely attacked in the track’s second half, their tranquility abruptly shattered by crushing tentacles of static – a contrast reminiscent of the effervescent burblings of Fennesz’s ‘Endless Summer’. The sophistication of these arrangements is striking – where previous records riffed on Detroit techno and remained identifiably linked to their influences, here Halo has struck out into genuinely new territory. It’s perhaps ironic, though, that what’s blasted her music headlong into the future is its re-integration of those most ancient of musical devices – the unadorned human voice, verse/chorus structures – into environments they’re usually so thoroughly unfamiliar with.

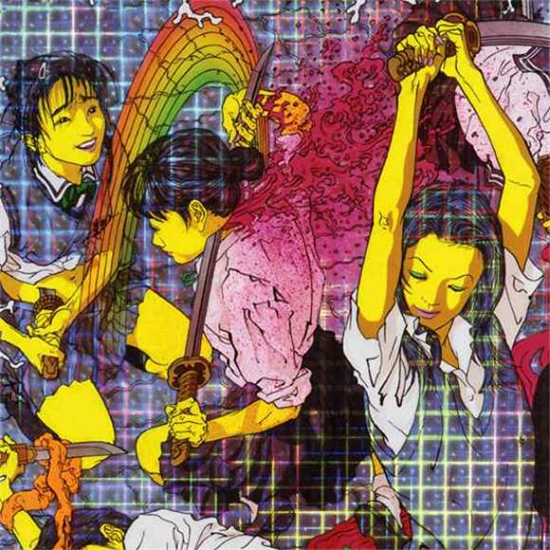

Quarantine‘s album art, by Japanese artist Makoto Aida, depicts a group of anime schoolgirls in cartoonish tones. On the surface it’s playful but closer inspection leads the viewer to double take: they’re gutting one another with swords, sending pink blood splashing and tumbling out across the canvas. As an image simultaneously delicate and brutal, it decodes the music contained within. It embodies a similar set of contradictions as this most intriguing of albums, denoting a world where extreme violence can be paired with extreme beauty. In Quarantine‘s world, drowning in the sea of information can be simultaneously exhilarating and isolating, and its inorganic background ambience can be brought to bear upon an album of songs grounded in human reality.