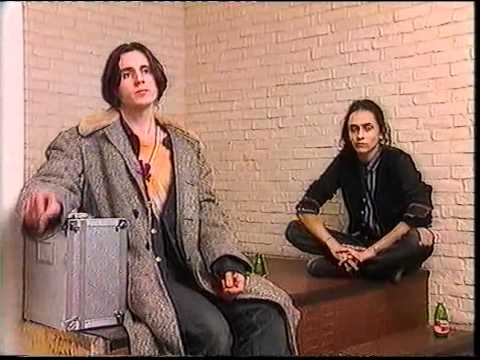

Levitation (L-R): Christian ‘Bic’ Hayes, Terry Bickers, Bob White, Laurence O’Keefe, David Francolini

Few stories have a beginning and an ending that one can pin down with any degree of precision, and the story of Levitation is no different. You could say that it began with the burning of bank notes in the back of a tour bus and ended with the break up of a band before a packed London audience, but these are arbitrary points in a tale that includes bust-ups, breakdowns and bankruptcies, a drive-by shooting and drugs. Lots and lots of drugs.

The tale of Levitation is as messy as any you’ll hear, a saga of gritty determination, musical communion, poor communication, extreme music and even more extreme exhaustion. But, despite a series of EPs, they left behind just one album, Need For Not, a record made by some of the finest players of their generation, men who took the stoner ambitions of the shoegaze scene to previously unscaled heights and won the admiration of some of the most powerful people in the music industry. Their second album, Meanwhile Gardens, currently remains unreleased.

The history of music is full of also-rans, but few flared so bright, burned out so fast, and left behind, in their ashes, such a concise but exceptional body of work as Levitation.

The Players:

Terry Bickers: Visionary, brain-melting guitarist for The House Of Love

David Francolini: Stalwart of the Bristol scene, a ferocious and hugely innovative drummer

Christian ‘Bic’ Hayes: Former bassist for The Dave Howard Singers and guitarist for The Cardiacs

Laurence O’Keefe: Bassist with The Jazz Butcher, cult Creation Records signing

Bob White: Keyboardist, former bandmate of Hayes from free festival psychedelic rock act Ring

Andy Saunders: Levitation’s first manager, soon to become a publicist at Creation Records

Mike Smith: A&R scout at MCA Publishing, later to become Managing Director of Columbia Records

Charlie Myatt: Booking agent, later to set up 13 Artists, home of Radiohead, Arctic Monkeys, Sigur Rós and more

Andrew Winters: Co-founder of Ultimate Records, who released Levitation’s first EPs and a compilation, Coterie

Dai Davies: manager of The Stranglers, promoter for early Sex Pistols shows

The Story:

Francolini: I turned up in London to see my mate Paul Mulreaney, who was the drummer in The Jazz Butcher and worked in the storeroom at Creation. A bag of mushrooms in one pocket, a bottle of vodka in the other, I went in, and Paul was still finishing off. I went up the rickety old stairs into the office, and there was Alan [McGee]. I nervously fiddled with this piece of paper that was on the table and went, "Oooh, that’s quite a tour." 45 dates. Alan was, "Oh Dave, we’ve got a problem with the support band, Something Pretty Beautiful. They need a drummer." And I went, "Well, I’ll do it. Give me the number." I arrive in Bermondsey 24 hours later, and we learned the set in the afternoon, then jumped in a van and drove up to Leeds, walked on stage and fucking had it. And then Terry walked on stage and fucking had it. He was playing exceptionally explosive guitar on that tour, quite at odds with the plodding nature of House Of Love, as he plunged the headstock of his CMI guitar straight through the speaker cones of his Fender twin and then, spinning on his heel, caught the resulting retina-displacing squall of feedback and turned it into another epic chiming riff. We sort of caught each other’s eye. And that’s how we met. And 42 days later was the fateful day.

Saunders: I knew Terry from the Camberwell squat days, and because the House Of Love were a rising star at that particular time. I bumped into Terry down the Harrow Road, and it was around the time that the House Of Love had split up and it had all been very messy, and there were all these stories about the fact he set fire to money in the back of the transit van, and they kicked him out because he was too mental.

Bickers: It was one five pound note. It’s been blown out of proportion.

Francolini: You could tell it had been building for a while. Yes, it was dramatic, but he was true to himself, to his soul, and that’s all that I was in the game for. He was my Hendrix. The man I had been waiting for. I seized the opportunity with both hands. We got out of the van together.

Bickers: I wanted a new project. I needed to have that focus to continue. I’d been in House Of Love for a few years, and bands before that. I needed to continue with having that as a focus in my life.

Hayes: When I was playing bass with The Dave Howard Singers – who, like The House of Love, were based in Camberwell – we were in The Grove pub one evening when Terry came in. Terry asked Dave how it was going with the band, and Dave must’ve said something about being skint. Terry produced a chequebook, wrote out a cheque on the bar and handed it to Dave ‘for rehearsals’. It was a little like Ace in Quadrophenia dealing with his fine in the dock. I’d never seen a musician with a chequebook before, and certainly not one dipping into his pocket for another.

Francolini: I just wouldn’t let go once I’d spotted Terry. Shortly post-departure, we were walking in London town and he spotted Bic on his courier bike when we were stood at Seven Dials in Covent Garden. Bic sitting astride his bicycle there on that wet, blustery grey day is etched indelibly on my mind. Terry knew Bic through his South London musical friends and we arranged to meet him at a studio we were booked in to.

O’Keefe: I met Dave in 1988 when the Jazz Butcher played with the Blue Aeroplanes. He did the drum soundcheck for his mentor, John Langley. He was part of the young blades of exceptional musicians to come from Bristol, and did his very best to impress by playing the drums at us. If only I had walked away at that point. His energy and enthusiasm infected most people that met him, myself included, and a friendship developed. Maybe a year later, I was at my father’s house in Greenwich when he called and said he was playing with Terry Bickers and that I should come along. I can still recall the Bristol burr in his accent as he said "… and don’t say I don’t give you nuffin’…"

Francolini: Laurence was, and still is, a stupidly good player, and I suggested to Terry we have him for our own. Then, after working with Bic a couple of times and getting on really well, he suggested that we meet the multi-talented Bob, with whom he had worked in a couple of bands previously.

White: Bic came over and played me some songs they’d be working on, but I can’t really remember anything about what they sounded like. It must have been enough to make me interested in going along to a rehearsal, the first of which I recall: I met Dave first and thought he must be Terry. Well, he looked like a rock star to me.

O’Keefe: Terry had black hair, black boots and a red guitar and was very confident on stage. He had genuine charisma and obviously warranted the attention. I remember showing up late to a rehearsal room in Camden and Bob was playing the bass to what became ‘Firefly’. I stood outside & listened. It was really quite exciting. It seemed we were starting from an intermediate level and, in improvising together, all sorts of musical goodies fell to us.

Hayes: We instinctively took to improvisation as a method of composition. It was effortless. It seemed the more we put in, the more it gave. It was what drew us together and propelled us forward. We just gelled, and I think it’s fair to say we all knew it very quickly.

White: It was all very loose. There was no master plan. It was obviously something that had come together around Terry, but it was really a combination of some strong personalities that found its focal point in him.

Hayes: I was playing guitar in Cardiacs. They were the band I left for Levitation. I loved Cardiacs and thought they were the best band in Britain at the time. That’s how much I believed in Levitation. The chemistry was explosive.

Francolini: It was obvious to me that we had hit on something fresh-ish and new-ish because nobody liked us at all to start with.

O’Keefe: The Jazz Butcher hated the Levitation demos I played to them, so I knew I was going in the right direction.

Francolini: Musically what we were trying to do was quite complex in places. Those songs that fell out of the ether, some of it took applied work and consideration and thought. Meanwhile, there’s the practicalities of living and having no money, and there’s the tornado of which you are the five points, this cacophonous noise. You don’t really have a lot of time to think. You just do.

Bickers: Yeah, I’d probably go along with that. There may have been an opportunity to think some more, but that opportunity wasn’t capitalised on. It’s like that with any band that starts to pick up momentum.

David Franciolini

Saunders: I met Terry, and he poured it all out to me: what a difficult time he’d had, and what a nightmare it had been in the House Of Love, and how difficult he was finding life, and he really wanted to get back in the game. I said to him, "I know a lot of the people at these record companies, maybe I should help you get some demo time", which is something major record companies do: they’ll pay for some studio time to demo new material from artists they’re interested in. So I think Chrysalis and Atlantic gave us some money to go and do that. I also had a relationship with Mike Smith, and he was at MCA Music Publishing as a lowly scout – he’s obviously now one of the most powerful men in the music industry – and he took it to Paul Connolly, who’s now the chairman of Universal Music Publishing, but at the time was running MCA. Paul immediately said, "Yeah, let’s do it, how much do you want?" I plucked a figure out of the air, and we did the deal. And it was quite a lot of money, certainly enough money for Terry to move on.

Smith: I was absolutely stunned by Terry. He never used power chords. He was very much picking out notes the whole time on the guitar, so you’d be getting this big washing great orchestra of sounds coming out. But he’d be running up and down the stage, convulsing, like someone was literally wiring him up to electricity the whole time. There was something about Terry: it felt you weren’t dealing with somebody that was a regular guy at all. It was like you were dealing with a shaman. There was something utterly magical about him. And put a guitar in his hands, he was pulling sounds out of the guitar that you’d never heard before. Kevin Shields was the only other person of that generation that was doing it, maybe J Mascis.

Saunders: I knew a booking agent and said, "Any shows coming up that we could get Levitation on?" House Of Love had made a bit of an impact, and Terry was a key part of that, so lots of record companies were interested, but they said they wanted to see him play live. And I thought, "Well, rather than him go and do a load of stuff in the UK, why don’t we do some shows in the relative anonymity and privacy of the continent and then come back, and we’ll be tight, and rehearsed, and we’ll play some killer shows in London and that will seal the deal?" So this agent said, "Ride are going out, and there’s some dates with 808 State, so if you want I can get you on these bills".

Smith: I took quite a lot of time off work so I could tour manage them around Europe. It was a remarkable experience, but incredibly challenging. Terry was just one of five very interesting and diverse people in that band. It was a pretty intense tour done on an absolute shoestring, to the point of going out busking so that we could get food and lodging for the evening because we just ran out of money because Terry had spent the tour float. I always felt you were dealing with somebody who didn’t run by the same rules as everybody else.

O’Keefe: The splitter van had ‘Good Rockin’ Tonite’ written above the driver’s compartment. It was extremely painful to be seen emerging from that vehicle in daylight.

Saunders: I went to the Paris date. That’s where Terry set his guitar on fire. It’s also where we had an interview with Rapido TV, and he said he’d never been paid any royalties from Creation. I got home and there was a letter from Alan McGee’s lawyer on my doormat basically saying, "We’re suing you for libel." I rang up Alan and we had a really good chat, and he went, "Yeah, he’s a bit mental", and I went "Yeah, he is", and he went, "Poor you", and I went, "Give us a job, then", and he went, "Alright."

Bickers: We had a rehearsal studio, and Bic and Dave would go there most days as a 9-5 type thing, and hats off to them for doing that, because it’s someone who’s really appreciating the opportunity that they’ve been given. Certainly Dave was living that band thing 24/7.

Francolini: We worked incredibly hard, listened to a whole lot of records, smoked a whole lot of pot, took a whole lot of acid and ecstasy and rocked the fuck out. Those guys knew what it took to get there, which is lots and lots of fucking effort. And you can talk about the acid and you can talk about the ecstasy, and that’s a lot of fucking toss. We just worked fucking hard. And that’s the way you do it.

White: Psychedelics we had all done before in fairly generous quantities, but it wasn’t part of the fabric of the working of the group in the fundamental way that pot was. We had to always make sure there was pot around or things went weird very quickly. People got very edgy.

O’Keefe: I recently saw some photo shoots from 1991. There must have been a lot of drugs. Unforgivable hair. I should have been punched to death.

Francolini: I think you could count the times that at least one of us wasn’t high when we were all together on one hand. Yes, we were very fucking far out.

O’Keefe: There was desk tape of a show when we supported All About Eve. We could hear Terry talking between the songs as if he were commentating a Test Match: "Lovely delivery there…"

Bickers: To some extent I think I bought into the myth of who I was in terms of the guitar maverick.

Saunders: It was the Gulf War, and I got a call from Steve Lamacq at the NME, and at the time he was the news editor, and he went, "Andy, I’ve got a story: Terry Bickers has just been observed on a ladder on the Great Western Road on a billboard poster writing in four foot high letters, ‘Not in my name’ or ‘Blood on your hands.’" I said to Steve, "You and I have known each other a long time, please don’t write that", and he went, "But it’s such a great story." I said, "It’s going to have Bonkers Bickers as the headline, isn’t it?" and he went, "Obviously." I said, "Let me talk to Terry and find out what’s going on."

Bickers: Yeah, I did spraypaint a billboard once, and then I got accosted by a plain-clothes policeman, but I luckily had some baby milk and nappies in my bag and he let me off.

Saunders: So I ring Terry up, and Terry’s like, "It’s about, like, the war, and I’m going to move everybody to Scotland because it’s just, like, everybody’s going to die and I just had to make a political statement." And it was just like, "Fucking hell, so you’re mad."

Bickers: I suppose I had some concerns about how I was perceived, although I don’t think I worried about the pressure to deliver musically. It was more personal pressure and wanting not to be mocked in the press.

Saunders: I’d get a call at five in the morning, and Terry’d go, "Hello?" And I’d go, "Hello?" And he’d go, "What do you want?" And I’d go, "Terry, you rang me". And he was like, "Oh, did I? Oh, sorry, man" and put the phone down. There was a lot of bad drugs involved, the wrong kind of drugs. I certainly wasn’t an angel in that respect myself. But when you start talking about Class A drugs and the kind of people that started to be around them, at that point, I was like, "This is not for me, I really don’t want to do this. It’s too scary, basically." Frankly, I’d say he was mentally ill at that point.

Bickers: I don’t think it was particularly severe…

Smith: I vividly remember him coming into my office with a Japanese ceremonial sword that he unsheathed and swung into my face and said, "I’ve bought this to protect my family." It was a wonderfully dramatic and romantic thing to do, but it was very difficult. It’s easy to forget that the House Of Love were tipped as a band that were going to be as big as U2 in 1988. Everybody expected Terry to be able to carry forward the special energy that had been there with the House Of Love and make it relevant in a world of Stone Roses and Happy Mondays. Like an enormous amount of sensitive people, you take a lot of anaesthetics to cope with it. There was a degree of substance use at that time that brought out a different side of his personality that wasn’t his true personality.

Bickers: If anything it was someone trying to handle once again, after only a few months absence, being in the public frame. I enjoy performing, but maybe being a public person isn’t totally natural.

Smith: Dai was another great personality to throw into it. A very lugubrious Welshman, very proud of his Welshness, who drove round in a Jensen Interceptor, and had been absolutely at the centre of punk rock and completely believed he had a band that he could conquer the world with…

Davies: I got involved because Mike Smith asked me to manage them. I went to see them at a pub in Windsor (The Old Trout). I’d seen the Pink Floyd play there when I was about 17 on a trip up from Wales, and I saw Levitation in the same place more than twenty years afterwards. That seemed to be significant.

Bickers: I took myself quite seriously at the time. I still do! I often found the ‘Bonkers Bickers’ remarks hurtful. Other people might have just brushed that off. I was still quite a fragile individual.

Davies: Terry wasn’t bonkers. He subscribed to somewhat outlandish conspiracy theories, and he didn’t like the corporate world, but that’s a hugely common thing amongst young people. I remember him coming in to see me with the idea of doing a tour entirely by canal boat. On close analysis it doesn’t stack up as possible, but it wouldn’t have been a bad idea to do two or three gigs. So you can either interpret that as bonkers, or you can interpret it as a very smart marketing idea that would have aligned the band with the green movement.

Winters: When I came to start Ultimate Records, Terry had sent me some tapes of Levitation which were impressive, but seeing them live was something else: Terry, Bic and Francolini were amazing musicians. It might have been prog rock, but it anticipated grunge before its time and most ’90s alt rock. They would have scared the shit out of any audiences before punk, and you’re talking here to someone that saw Pink Floyd, Can, Amon Düül, Nektar and many others between 1970 and ’74. Anyone who knew or loved anything about music couldn’t fail to be impressed, though I did notice more than the usual amount with earplugs.

Hayes: Each night was an experiment, a kind of spiritual bloodletting. Levitation were asking – ourselves, and anyone who came to the gigs – "How far do you want to go?"

Myatt: I remember the beauty, the enormity of the music and the space they opened up inside your mind. Genuinely mind-blowing.

Hayes: I loved doing the EPs. It was a really magical time. That’s when we started to get to know each other, relax a little more and laugh a hell of a lot. The halcyon days.

White: Ultimate were lovely people and a great springboard, but we needed proper bankrolling. (Rough Trade’s) Geoff Travis really dug it, and they seemed very keen to let us do what we wanted.

O’Keefe: Geoff left one of our New Cross Venue shows in tears. I still like to think of joy, of joy…

Winters: Ultimate and Levitation worked well together and we had high hopes. The only thing was we didn’t have an album contract, and couldn’t compete.

Davies: I thought it was really important to have them be on an independent record label in Britain. So it was a UK deal with Rough Trade, EMI in Germany for Europe and Australia, and Capitol for North and South America. We had all the advantages of being on an indie in terms of freedom and image, and all the advantages of being on a major in terms of clash and clout. I thought at the time it was perfect.

Hayes: Making Need For Not was very peaceful. We lived together in a house like The Monkees, worked very intensely, watched films together, sat down to meals together, listened to music, laughed and slept loads.

O’Keefe: The dark bullshit was yet to come, so it captured that moment, which really should be what it’s all about.

Bickers: I think we were on top of our game. I’m always saying to people, you want to play your material in. And that’s the result when you’ve done that: you know what you’re doing.

Myatt: They were perceived to be a big band, but they weren’t massive ticket sellers. Other artists loved them so they were offered many supports: Sugarcubes, Psychedelic Furs, Spiritualized, Mercury Rev, My Bloody Valentine. We used to package them with other artists so we could play bigger rooms and make them look as big as they were perceived.

Davies: We got the album out very quickly, and that went to number one in the Indie Charts.

Hayes: Our success is not defined in numbers, record or ticket sales, and never will be.

O’Keefe: We signed to Capitol on the roof of the famous round tower in LA. The President, Hale Milgrim, showed us the Beach Boys master tapes and reverb tunnels in the basement. They were ready to clear the runway for us. It’s strange when I pass it now to think I was ever up there.

Davies: Capitol were really supportive of the act. Alison Donald, who signed them, was a key figure in Capitol and she was staking her reputation on Levitation. The president of the company really liked them. If you need to be dramatically successful you need a whole bunch of people at the record company to really like them and believe in them. And they had that. They’d reached that point where they were on the verge of having a big record if they carried on doing everything right. The number of records you get in shops and the number you sell are different things, but certainly there was thirty thousand albums in the UK shops, which is very, very good.

O’Keefe: Terry was acutely paranoid of America and failed to join us in New York and started to be a real drag.

Bickers: I had been on holiday in Mexico and was due to do a week of press in the U.S. but I decided to come back to the U.K. I’m not big on flying. I’ve got to fly to New York and then fly back to England, and I just wasn’t feeling comfortable with that prospect for whatever reason.

O’Keefe: It’s exactly like the apocryphal story of Deep Purple being told, one by one, that they had a hit in the States and a tour was imminent. Richie Blackmore was the last person to arrive and his band-mates excitedly broke the news. Richie replied, "I’m not going. But hey, I’m not stopping you…"

Bickers: This thing about the shooting…?

Francolini: I think it was me, Bob and Laurence went to a bar called The Smog Cutter in Los Angeles. And there was a drive-by. Just fucking riddled everything with bullets. Right outside the door.

Bickers: I don’t think there was a very close connection in any way. Things may have been said to the American people as a smokescreen for the fact that we weren’t going there. But ultimately I didn’t want to go particularly. I wasn’t thinking it in terms of the strategic campaign of what markets we’re going to break into or anything like that. I’ve never really been that business minded really.

O’Keefe: I now understand there were other concerns at that time, but that is the exact point at which the dynamic changed irreparably.

White: Rough Trade did what Rough Trade do: add a tremendous aura of cool to something, then go bust.

Davies: It didn’t affect things badly, though, because by then the records were distributed. It would have been disastrous if the money had flowed through Rough Trade, but it didn’t. We had the stock in the shops and the distributor had the stock. The guy who was running EMI Germany really believed in Levitation, and he said, "Well, we own Chrysalis, why don’t we put it [the next album] out through Chrysalis?" And there were some good people at Chrysalis who said they quite liked the record. It wasn’t as good Rough Trade staying in business, but that had already gone. So the band had two years of financial security ahead of them, provided nothing went wrong. Big proviso!

O’Keefe: Probably we all thought: ‘Blondie’. The press thought: ‘Jethro Tull’. The manager thought: ‘Another advance, another six months.’ And nobody else gave a toss. Least of all Chrysalis.

Hayes: We were in rehearsal studios, recording studios, or on stage, travelling up and down the country. In the shadows, ‘men’ were moving money around.

Francolini: My major concern was that the guy who signed us to Chrysalis tucked his trousers really high. Apart from that we got the money to make Meanwhile Gardens.

Hayes: I had a big row with ‘Power Trousers’, the head of Chrysalis Records, over artwork for the single we were about to release ahead of Meanwhile Gardens. "Poster bag?" I said. "We’re Levitation, not Chesney fucking Hawkes". Of course that single never came out.

O’Keefe: I think the writing is on the wall when you’re farmed out to a subsidiary. The wheels were starting to fall off at this point and poor Terry was not having an easy time of it.

Bickers: I was not where I wanted to be musically. I wanted to be in Talk Talk.

Hayes: We were due to tour America with Spiritualized, The Verve and Mercury Rev. I think it was all booked. What a tour that would’ve been! Robert Smith had got into Levitation and invited us to play with The Cure in Finsbury Park. We were actually on the poster for that one. That would’ve been our biggest gig to date. But it wasn’t to be.

Francolini: We’d been on tour. Before that we’d been mixing, and before that we’d been recording, and before that we’d been on tour for fucking about fucking two years.

O’Keefe: The lovely Charlie Myatt had regrettably assumed that we would have a tour bus for the trip from Glasgow to the Tufnell Park show the next day. We had not. Sleep, neither. We were fucked. The show was OK. Not a ten, but perfunctory enough. We then rounded to the home straight of ‘Attached’ when something suddenly went ‘dink ‘. Obviously the demons within and the repressed emotions were released, along with all the other toys from the pram.

Bickers (14 May, 1993, live on stage at the Tufnell Park Dome, London): "Levitation certainly are a lost cause as far as I can tell. We’ve completely lost it, haven’t we? Haven’t we?"

White: Thank fuck that’s over.

O’Keefe: Darling T, we hadn’t even got close to it, yet alone put ourselves in a position to ‘lose it’. It was an immensely unprofessional, selfish and contemptuous act to treat your friends and partners to such a public display and, ultimately, was humiliating for us all.

Francolini: It broke my heart. We finished with ‘Attached’: "Strings attached to all sorts of friendship. Bound so tightly, so tightly they cut."

Bickers: I remember being backstage afterwards and a friend called Rock Pete saying he thought I had done the right thing. Bic’s girlfriend and my girlfriend had a row. Emotional displacement, you might say?

Davies: People were crestfallen. I think Terry left with his girlfriend pretty quickly. The band were fed up with him after his American decision because that affected the rest of them so much, so when he stormed out – this is reconstructing it twenty years later – I think the subsequent mood from the guys was, "At least he’s gone."

White: The period leading up to this time had been incredibly stressful and torturous with someone who clearly didn’t want to be there anymore, and it was obvious that it was going to implode at some point. We’d actually had a meeting with the four of us about whether we should pre-empt all this and kick Terry out not long before he left. I remember feeling relieved and saying to Terry that he should go and do something else for a while, find whatever would make him happy.

Davies: It made me give up management.

Bickers: I don’t think I was having a breakdown, I just wanted out. It felt like self-preservation at the time. I think the logic behind the way I did it was that I did not want to enter into a discussion with the band or management because I thought I would have been persuaded to carry on. For a certain period playing and singing in Levitation felt like acting. All of the angry, shouty stage routine was not really me, or at least not a role that I relished acting out every night. I just didn’t like the energy surrounding the group towards the end, and I felt a distance between myself and the other members and entourage, although I accept that I may have been responsible for this feeling of alienation. I regret how I handled leaving the group, and I realise it was a shitty thing to do, but I just couldn’t see a way through.

Davies: He’d been through a difficult experience, followed by another difficult experience, and it’s impossible for anyone other than him to say what extent drugs played a part in that. Did he use drugs because of the depression he was experiencing, or did the use of drugs trigger those events? Who knows?

Hayes: I think Terry could have definitely done with more support. He had begun a family and had pressures outside our creative bubble that were out of my experience. I’m afraid I was way too self-absorbed to appreciate the difficulty of the situation he was in. He didn’t lay it on anyone but struggled on until it became too much, and then it was too late. I couldn’t and didn’t take the time to listen and empathise, and this is something I very much regret.

O’Keefe: We all tried our best to reassure him and support him, but I don’t think any of us realised what he was going through because of his outward image and our collective naivety. I can now reflect how tough it actually was for him and what an amazing job he did under the circumstances. We did see the darker problems manifest towards the end, but we were, or at least should have been, in a band. Not in therapy. They were another band.

Myatt: I think you have a view that they were mashed up by the machine – that is probably partially true – but the seeds of their undoing were there from the start. I am not sure what they could teach bands now. Probably talk to one another and be sure you want the same things. Keep the rock & roll on stage.

O’Keefe: Charlie had a new act called Radiohead support us a few times. They would stand at the side of the stage, watching. "You should talk to them, they really like you," Charlie would say. "Nah, we’re off to the pub," we would chorus. "Let us know when they’re done." I remember being at a party somewhere after Levitation imploded. It was in a basement, dark and drunk. Someone put on The Bends and my penny dropped. Heavily. They had achieved everything I thought we could. There was a vacancy and we let Radiohead fill it.

Smith: Levitation seemed to have arrived in five minutes at the point it took Radiohead ten years to get to.

Bickers: I often have listened to Radiohead, and kind of go, "That’s what I do!" I feel an empathy with what they do. I’m a big fan.

O’Keefe: We burned brightly for a short while. We were luckier than many more deserving bands. We even sold some records and made some friends along the way. But we failed to realise our true potential. We shouldn’t have. But it was sure fun trying. Better to be a spike than a wavy line.

White: It was an amazing time in my life, which I’ll never forget. It was exactly as long as it was meant to be.

Hayes: We reached out and really moved people. The tragedy of the band was we were unable to reach out to one another.

Bickers: Learning how to communicate better would have helped no end. There’s always this paradox of people who’ve been trying to get somewhere with their music or their professional music career for years and years and years, and then suddenly that happens, then there’s all these other factors come into play which no one knows how they’re going to deal with until they get there. It’s something to strive for, but you thought it was going to be different when you got there.

Francolini: Being in a band that starts to fly is like mounting a racehorse bareback. It starts to gallop and you just hold on to the mane for dear life and pray you don’t get thrown off.

Smith: They really did live right at the edge for such a long time, and that approach and lifestyle is completely unsustainable. They were dreamers that weren’t remotely interested in commercial success. They just wanted to make music, which is a fantastic ambition and the one that people should have above all else.

With grateful thanks to all the participants, especially David Francolini, and also to Chris Tomsett and Jo Bartlett

Photos by Liane Hentscher