This piece was originally published in 2012 to mark the album’s 30th anniversary

Nick Cave – a tall, wiry, spike-haired figure who has been prowling the stage with all the agitation of a condemned man about to make his final walk to the hangman’s noose – has bassist Tracy Pew in a headlock. The wriggling supplier of the low-end rumble could easily be a reject from The Village People; a moustache rests on his top lip, the cowboy hat on his head struggles to remain in place during the ensuing tussle while his black fishnet t-shirt barely conceals the underfed torso beneath.

As the pair grapple on stage, Cave launches a second violent front as his booted foot lashes out and connects with bone, cartilage and teeth at the lip of the stage. Immediately, several sets of hands reach out from the melee and grab both the howling singer, his face contorted in a mixture of rage and confusion, and his twisting cohort. Within seconds they fall backwards from the stage to the floor below and in the blinking of an eye the duo are engulfed by flying fists and angry feet raining blows and kicks with an unrestrained savagery. Amid retaliatory punches of his own Cave’s grunts and guttural screams remain unbroken as Pew’s bass guitar neck is seen making frantic upward stabbing motions in the direction of his assailants.

The music, an unholy collision of blues, rock & roll and free jazz seemingly fuelled by the nastiest variant of bathtub speed cut with cheap scouring powder, plays relentlessly on. Guitarist Rowland S. Howard, an emaciated figure that suggests an ongoing estrangement from three square meals a day, stares at the violent scenes from eyes set in darkened sockets with a sneering sense of disdain, as if the pair being torn by the audience deserve everything they’re getting. The scrapes and skronks that emanate from his guitar apparently strung with finger slicing cheesewire refuse to break their stride.

To his left stands second guitarist Mick Harvey. Unlike his counterpart, the look on his face reveals the haunted expression of someone who has seen these chaotic scenes once too often for the experience to be fun any more. Behind them, the flailing figure of drummer Phill Calvert isn’t so much keeping the beat as struggling to catch up with the maelstrom that’s being created in front of him. Little wonder, then, that this is his last concert with the band before they up sticks and leave London’s unwelcoming streets for the untamed environs of West Berlin to continue as a quartet.

This is The Birthday Party in full flight at The Venue in London in August 1982 and within a year the group will cease to exist. Blazing hard and blindingly bright, The Birthday Party were a magnesium strip of rock & roll intensity destined to burn out rather than hang around for the long haul and in Junkyard the band achieved its high watermark as a quintet.

Released in May 1982, Junkyard’s uncompromising contents signalled both the oncoming demise of the band responsible for them and rock & roll’s logical conclusion. Harnessing the power of The Stooges’ Funhouse with the limitless possibilities offered by Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica, The Birthday Party were a product of the uncertain times that created them. With Thatcher and Reagan only just getting into the stride that would alter society, culture and economics beyond recognition, the tumultuous and apocalyptic music of The Birthday Party – though never making any reference to the outside world that existed beyond their own universe – was the unwitting soundtrack to a time of death, darkness and decay.

Erroneously tagged as “goth”, The Birthday Party nonetheless owed a debt to the gothic Americana of a mythical Deep South steeped in sin, revenge and retribution. Troubled music for a troubled age, Nick Cave’s world was created in a white-hot blast of visceral energy, gut-wrenching violence and Dadaist stupidity while the work of his band mates fleshed out the vision to devastating effect. Here, blasphemous imagery fraternised with scenes of murder, brutality and sadism as it rolled and revelled in a trash aesthetic that belied the intellect behind it. The noise created by the band was at once familiar – a wild mutation of rock’s primordial slime mixed with a nightmarish interpretation of Elmer Bernstein and a skewed vision of the blues spewed out rather than played – yet startlingly new and all underlined by an inevitable finality.

With the passing of 30 years, Junkyard still sounds as if it’s waiting for rock music to catch up with it. Throwing down a taunting gauntlet to subsequent generations of musicians, this feral collection of songs simultaneously closes a door on something that can’t be repeated or improved upon. The distance of time has failed to reduce its sonic power and revisiting Junkyard three decades after its birth is to rediscover an album more melodic if no less manic as was initially perceived.

As Tracy Pew’s bass growls the introduction to opener ‘She’s Hit’ over Phill Calvert’s tinkling cymbals and the snaking interaction between Rowland S. Howard and Mick Harvey, it becomes manifestly clear that Junkyard is a far more nuanced and unpredictably dangerous beast than its predecessor, 1981’s Prayers On Fire. Even before Nick Cave utters a word, the album’s grime, torment and filth ooze from the speakers to entwine themselves around the listener like arid, high-summer heat. The odour of spilt whiskey and cigarette ash ground into a carpet is palpable but this is far from a crumpled body lying in an intoxicated heap among burnt spoons and bloodied needles. The threat of menace is never far away and not once do The Birthday Party offer an iota of slack or a sense of security.

As exemplified by the lobbed hand grenade that is ‘Dead Joe’ – a shocking detonation that stands in stark contrast to the twisted blues of ‘She’s Hit’ – The Birthday Party harness their live muscularity in the confines of a studio with terrifying conviction. With engineer Tony Cohen helming most of the album, Junkyard is an album awash with top and bottom end dynamics with very little mid-range to re-create the confrontation that the band regularly generated on stage. The reverb that drenches ‘Hamlet (Pow, Pow, Pow)’ plunges the listener into the centre of the action, a nightmarish scenario wherein William Shakespeare’s totem of indecision is transformed into gun-toting, murderous horn-dog.

This is a world where perception is turned upside down and received wisdom is challenged at every turn. The blasphemy at the heart of ‘Big-Jesus-Trash-Can’ sees the Messiah mutating into an infernal version of Elvis Presley where his gold lamé suit is stained with Brylcreem and crude oil as Mick Harvey’s mangling of jazz breaks stomps over any notion of rock & roll convention.

While most eyes focus on the untamed figure of Nick Cave, Mick Harvey’s role in the creation of Junkyard cannot be understated. A multi-instrumentalist with the kind of golden touch that can only enhance the music he’s working on, not only did Harvey’s songwriting input grow (see ‘Kewpie Doll’, the still-disturbing ‘6” Gold Blade’ and the aforementioned ‘Big-Jesus-Trash-Can’) but his increasing contributions on the drum kit revealed that Phill Calvert’s days were numbered. Listening to ‘Hamlet Pow, Pow, Pow’ and ‘Dead Joe’, Harvey’s drums parts are as far removed from straightforward time keeping as one can imagine and his subsequent move occupying the drum stool in the wake of Calvert’s departure proved inspired.

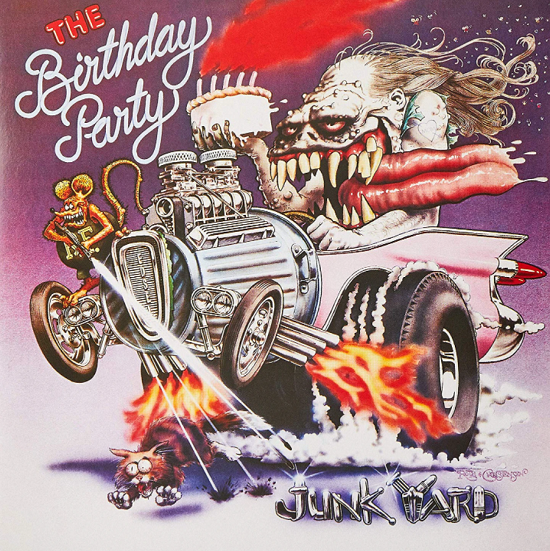

In keeping with the music contained within Junkyard’s grooves, the cover art by custom car designer Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth was several removes away from the graphic mores of the age. Unrestrained by notions of taste or intellect, the image of a souped-up Cadillac driven by a flea-ridden, wart-encrusted monstrosity revelled in visuals that was sharply odds with the times that spawned it. It isn’t just the music that challenges here; the artwork suggests a decadence and nonchalance that turns its back on a troubled world and refuses to bow to convention and supposed good taste.

It couldn’t and didn’t last. Despite a move to Berlin and the release of further stellar music, internecine fighting and ongoing drug problems conspired to leave The Birthday Party a treasured memory among those fortunate enough to bear witness to the madness, terror and sheer excitement they unleashed on a largely indifferent world. Junkyard still matters; a high example of uncompromised music and art, this is an album that exists purely on its own terms. Creative, bold and daring, these ten songs refuse to pander or kowtow as they dare – nay, goad – from across the decades for someone bold enough to seize their baton and run with it. Any challengers?

Junkyard is a very different beast from its predecessor, Prayers On Fire. Was that a natural evolution or did you have that sound specifically in mind?

Mick Harvey: I think that Prayers On Fire was probably a stepping stone somehow to what we were doing live in the intervening time and it made us feel that we wanted to go to further extremes. Some of Junkyard is quite harsh; listening to the bass, there’s quite a lot of bottom end in there but nothing much in the middle. There’s a lot of attack and snarling in the bass that you wouldn’t normally hear and a lot of treble! We were pushing that deliberately beyond what was acceptable; that’s what we were doing in a live setting, anyway.

It was always very difficult for The Birthday Party to re-create what we were doing live on record. Part of what we were doing was really about the interaction, I suppose. It was about that live situation and suddenly being in a studio and recording that stuff was a different dynamic, obviously, and trying to push the sound aspect of it was probably an attempt to compensate for the lack of frisson between the band and the audience. We tried to push it as far as we could, basically.

The Birthday Party were very much noted for that frisson between audience and band and, indeed, band member and band member. How difficult was that to recreate in the studio?

MH: I’m not sure we were trying to recreate that. When we were in the studio recording our songs it was a very different situation. I don’t think we ever kind of thought about actively doing that. We never really discussed anything much but it certainly seemed that we had some kind of mission and some kind of unified goal amongst all the friction. We rarely discussed what we were doing. We did things intuitively and so when we came to the studio we were probably aware that it was difficult to recreate that live electricity. We were only really aiming to recreate the songs and at the same time trying to push them to an extreme in the sound because it was completely inappropriate for us to be trying to record ourselves like a normal band. We certainly flew in the face of what was a normal band; that’s what we were doing.

Was your music a reaction to the situation you found yourselves in? My understanding is that you were living in poverty in a series of squats.

MH: This is a kind of a popular history but that isn’t necessarily true. Nick and Rowland were moving from squat to squat and the rest of us weren’t really doing that. That was probably brought on by not having any money and whatever money they had was spent on their drug habits. But it’s impossible to appraise how much of the music was down to living in harsh circumstances and reaction to them.

The Birthday Party’s music was more a reaction to what we saw in the music scene when we arrived in the UK and what we saw there and what was happening artistically in what we perceived as some kind of scene and a common area that we might have had with other musicians. To us, the New Wave and punk and stuff was about artistic freedom and getting to the heart of the matter and doing all the other stuff that came with it. When we got to the UK in 1980, punk was long gone and it had gone in different directions as either a fashion accessory or being commercialised. Obviously, there were still certain things that were holding up and we were trying to hold on to our artistic values. There weren’t that many bands holding a hard line artistically and that was something that we were really disappointed about. That was something that had been undermined by the time we got to the UK but this was an artistic response.

How isolated did The Birthday Party feel from other bands and what was going on?

MH: The scene in Melbourne and what had been happening in Australia in ’79 had been really healthy and really fantastic things had been going on. Everybody was interacting – musicians, artists, film makers.

You seem to be taking more of a central role within The Birthday Party at this point. You drum on a couple of tracks and your song writing credits increase. Was the weight of the band falling more on your shoulders?

MH: I didn’t really feel like that at that time. It was around the time of The Bad Seed EP that I started to feel like that when I really did start to co-write all the songs and stuff like that. I think with Junkyard it still felt very much like just the same as it had been. Maybe I was getting more musically engaged and working out the drum parts.

What was the dissatisfaction with Phill Calvert’s work?

MH: Phill was a really good drummer but really, it was about the ideas. This is the thing about what I said about us never really discussing anything. We’d come to a song and we’d just start working on it and we found more and more that the drumming that Phill was trying to do wasn’t what we wanted. Things weren’t discussed but it became obvious that things weren’t working any more. Phill is a very good drummer and he’d been fantastic but by Junkyard he wasn’t really coming with us.

Tracy Pew was jailed for drunk driving and theft during the recording of Junkyard. How much strain did that put on the band?

MH: It’s hard to know. We were young and we just carried on. It’s weird because it was very disruptive and very confusing. When you’re young you just let those things overtake you and when you’re older you’re more philosophical about them and understand the stress that goes with them but you deal with them in a different way. When you’re younger you just blow through it. It still affects you but you don’t really stop and look at it; you just keep going. We couldn’t wait for Tracy to get out of jail but we had these shows to do so we managed to get through them with [temporary replacements] Barry Adamson and Harry Howard playing four or five shows each. It wasn’t ideal and I think we had to cancel some stuff.

It was the way we were living, too. We were living off plain rice but we always made sure we made money out of our gigs. That was how we survived. And of course, when we were recording there wasn’t much money around so we had to work out and juggle how to keep going until Tracy came back. You just keep going like they did in England during the war.

So how difficult was it to organise the recording sessions given the level of chaos going on?

MH: It was always a bit kind of confusing but the people who were in the most chaotic state wouldn’t have been involved in the organising anyway. You’d just hope that they’d turn up! It wasn’t like there were three or four other conflicting obligations. When the recordings were on a Thursday and Friday they’d kind of roll up eventually. It wasn’t that confusing.

With the benefit of 30 years’ hindsight, how do you view Junkyard now?

MH: I think it’s a great record, really. We did some weird things with the way we put it together and mastered it: we put the songs really close together so there were hardly any gaps; we put loads of treble on it and that crazy cover which I’ve never really liked. I’m sure it’s a great cover but I’m not sure it represents the album all that well. But the actual contents of the album are really amazing and they’re a very special set of recordings and that’s what really stands up; most people don’t look at the cover these days, they just play the music. Henry Rollins did a re-master of it and made the songs have longer gaps between them. There are re-mastered versions of it here in Australia that make it sound a bit more normal and probably more powerful and less of that messing with people’s heads. In the end it’s down to the songs and it’s pretty strong material.

Amazingly, it hasn’t dated at all.

MH: I think with just about anything that we did in the ‘80s – even with The Bad Seeds as well – and to this day, really, none of it pays lip service to any current trends or production ideas. We’ve never been interested in that. We’ve always been manipulating our productions and making them sound like we want them to. We’ve always been oblivious to current trends and that certainly that was the case with The Birthday Party; we were against the modern trends. The New Romantics were anathema to us! And the DX7 and all those 80s trappings were diametrically opposed to what we were trying to do. We made our own sound.