The story of the Ultramagnetic MCs often looks like a typical tale from the music industry’s contested margins. A talented bunch of street-level outsiders make a big buzz with a classic independent debut, get signed to a major and suffer the usual traumas of transition – the follow-up flops, the third album arrives on a third label and confuses fans, then the band dissolve, less amid acrimony than apathy. Yet, while most of that analysis is broadly true, the real picture is a great deal more complicated.

Their 1988 masterpiece, Critical Beatdown, wasn’t the all-conquering hero history tends to have turned it into: crafting their inspirationally unique style over a series of 12" singles, Ultra would have achieved the impact their music merited had the paperwork permitted the LP to come out a year earlier. Throw it in the mix next to the three acknowledged foundational classics of New York hip hop’s early Golden Age – the 1987 debuts by Eric B & Rakim, Public Enemy and Boogie Down Productions – and we’d today be talking about hip hop’s four horsemen, not the music’s holy trinity. Critical Beatdown is not only every bit as good as those records, a case can easily be made that it’s better than each and every one of them. It was hailed as a great album, but by ’88, it was just another one among many.

That it took until 1992 to follow that debut up undoubtedly cost the band any momentum they had left. They’d split up, briefly, but regrouped long enough to sign a deal with Mercury. The major label hadn’t really got any track record with rap at that point, and Ultra probably looked a good bet. The band had it all: innovative rap styles, adventurous and wide-ranging subject matter, a flair for incorporating melody and musical colour into beats routinely hard-edged enough to attract the attentions of hip hop purists. Kool Keith was a star-in-waiting; Ced Gee would have likely been the best rapper in the band if he’d been in a group with pretty much anyone other than Keith; nobody really knew what TR Love did most of the time but when he got on the mic he proved he could match Keith for rhyme invention if not sheer volume of provocatively experimental output; and as well as being a more than fine enough DJ, Moe Luv gave Ced a run for his money as a producer. The group had even managed to partially reintroduce themselves to the hip hop world via protegee and part-time member Tim Dog’s 1991 LP Penicillin On Wax, a rough-hewn affair spun around the magnificently offensive, non-more-hardcore single ‘Fuck Compton’ (unarguably the first salvo in what would later become hip hop’s East-West war). What could possibly go wrong?

At the time of its release, 20 years ago this month, the talk around Funk Your Head Up was that the label had done what majors often do: over-thought the record, tinkered with it, smothered the life out of it before it had had a chance to stand on its own two feet. Fans, expecting the second coming after the years waiting for more from the makers of such a classic debut, were underwhelmed: perhaps not wanting to believe their disappointment was all down to the band, most readily accepted this explanation. You’ve kind of got to feel for Mercury, too: they released ‘Make It Happen’ as the first single, and it’s undeniably great – a Ced Gee production meshing James Brown with That Petrol Emotion, over which he and Keith trade verses of pugnacious individuality and electrifying presence: but getting anyone outside a few rap shows to play it on the radio would have been impossible. It’s just too much – too different, too raw. In a word, "ultra".

But 1992 would prove to be a pivotal year in hip hop history, its close marking the effective end of the New York Golden Age and with it, a move away from sounds and styles based around intricate layers of rattly drum samples and James Brown yelps and hollers – the sound Ultra had helped invent, which had given other artists templates they’d turned into careers. While all that had been going on, Keith, Ced, Moe and Trev had gone missing. They helped create the space for the people who followed them to succeed in, but weren’t around to inhabit it themselves. While it’s not the equal of Critical Beatdown, the disappointed reactions to Funk Your Head Up were surely also partly due to the quality of the other music emanating from New York’s hip hop scene at the time. Back then, it was a pretty great LP arriving amid a glut of records that ranged from the adequate to the sensational: if a hip hop record this fine gets released in 2012 we’ll be planning street parties to celebrate.

"The album was so good we should have done more things – I was so pissed off that that energy of production was lost," Keith would later tell me. "But it’s weird, though. People always say, ‘You should blow up!’ And when you do blow up, they’re mad. It’s like a guy that plays a ukulele every day in front of a shoe repair shop. People walk over to him and say, ‘Yo, you should be in arenas!’ But as soon as he’s in the arenas they don’t like him any more."

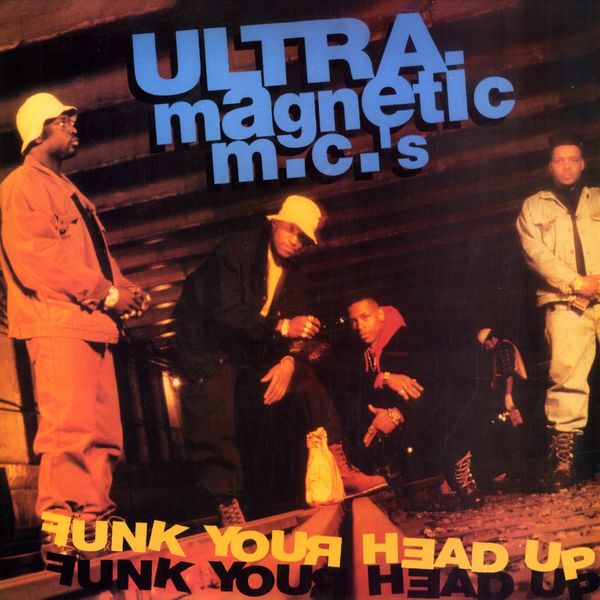

Heard afresh today, the main thing that’s wrong with Funk Your Head Up is that its 70 minutes of music is crammed, ruinously, onto just two sides of vinyl, meaning that the primary format fans bought it on effectively suffocated the record. It’s pretty well mastered, as a listen to a CD copy shows – but, try as the cutting engineer might, you just can’t transfer that much music to such a small piece of plastic and not lose significant amounts of its power. Today our worries about sonics – such as they exist – are over whether digital compression denudes music of its richness and tone; back then, the need to keep the cost of the package low by putting audio quarts into single-vinyl pint pots meant that fans never really got to hear the music as its makers intended. Throughout – even on the duds (the odd attempt at swingbeat, ‘I Like Your Style’; the thoroughly rotten ‘Porno Star’; ‘Stop Jockin’ Me’, which just doesn’t really work; the messy experiment-too-far ‘Chorus Line Pt 2’) – Ced and Moe’s production is superb: meticulously dense, as dust-encrusted and murky as the subway tunnel the group are pictured in on the cover, it redefines the concept of funk for the hip hop era and gives Keith’s rhymes, in particular, the sort of blaxploitation-via-sci-fi setting they uniquely demanded.

There’s nothing wrong with Ced’s rhymes on this record – indeed, it’s his best performance on an Ultramagnetic album. TR isn’t exactly overused, and his verse on the brass-fuelled swagger ‘Funk Radio’ is extraordinary – he comes close to out-rhyming Keith. But neither man can argue too hard with the contention that the album’s three key tracks are the ones that feature Kool Keith alone. ‘Pluckin Cards’, ‘Bust the Facts’ and ‘Poppa Large’ are extravagant, extraordinary – hip hop from another dimension.

Before we get into the specifics of his work on Funk Your Head Up, there’s a few things that have to be explained about Kool Keith. At the beginning of ‘Bust the Facts’, a superb evocation of the block party era with Keith imagining he’d been a performer not just an attendee, he introduces himself as "the best emcee in the world". It may be part of a four-minute historically based fiction, but there are plenty of reasons to examine the claim seriously. There are emcees who’ve achieved nothing by comparison to him who have become millionaires off the back of far weaker discographies – people who’ve probably dismissed him as an aberration or an irritant, or who maybe never really bothered listening to him, who’ve made fortunes out of concepts Keith invented. Some say he was the first rapper to rhyme off-beat – to insert syllables into the spaces between drum sounds, to make rap into a fluid element of the music, allowing rappers to become soloists rather than limiting them to a vocal form of percussion. He got stick from this for his peers – some dismissed his innovations as juvenile, said he couldn’t rap; in 2004, Kool Mo Dee told me that when he was compiling his statistics-based book of the 50 greatest emcees, Keith had fallen just outside the list, with several other rappers referring to him as "the gibberish guy". Years before Wu-Tang and decades before Eminem, Keith was the first rapper to seriously get into the idea of multiple personas – the koolkeith.co.uk semi-official site lists 58 alter egos, some of which made entire albums (Dr Dooom, Dr Octagon, Black Elvis, Matthew), some appeared on individual tracks (Rhythm X, Robert Perry, Exotron Geiger Counter One Plus Megotron), and some that appear to have existed only on flyers or album artwork (Mr Green, Jimmy Steele, Elvin Presley). One of the few people to really get this part of Keith’s creative complexion was Liam Howlett who, when he finally managed to fulfil his long-held ambition and record with Kool Keith (the track ‘Diesel Power’ is a highlight of the Prodigy’s biggest LP, The Fat of the Land), was able to get exactly the performance he wanted by asking Keith to rhyme as Rhythm X. And, partly due to the UK patronage of the then hip Mo’Wax label, partly due to the involvement of the hipster favourite The Automator, and partly no doubt due to decent distribution and promotion for the first time in his career, Keith pretty much came to define the "backpack" rap underground of the late ’90s with the Dr Octagon project – and ended up having to live with adulation heaped on him for stuff that wasn’t anywhere near being his best work by people who’d managed to ignore him when he was changing the musical world.

(Doc Ock is probably the main reason why a reunited Ultramagnetic are playing at the alternative festival I’ll Be Your Mirror in London this May, even though, while fine enough, it’s not even close to being the best thing Keith’s ever done. If hip hop had a stronger grasp of the commercial value of its own history, this would be an opportunity to exploit – the Kool Keith/Ultramagnetic back catalogue is a treasure trove of riches waiting to be rediscovered, but even by the subterranean standards of hip hop reissues their stuff has been curated poorly and most of the best material, including Funk Your Head Up and its associated singles, is out of print.)

There aren’t many musicians in any genre who’ve been as influential for as long yet remained as far from mainstream acclaim as Keith. The closest comparison may well be Ornette Coleman, who was derided by the jazz establishment and whose innovations were mistaken for incompetence, yet who won jazz’s only Pulitzer half a century after he started tearing up the music’s rule book, and has made his living by playing for the small number who understand his music and a slightly larger subset that either think they do, or think it reflects better on them if they appear to.

So: when Kool Keith says, as he does on ‘Poppa Large’, "I never rhyme like them," that’s not a brag or a boast, it’s just the truth. You get the sense that while rap for most rappers is about responding to the beat and engaging their wit, intellect, vocabulary and creativity, for Keith each and every journey behind the microphone is a chance to reinvent and reconstitute his entire creative process. The results can be chaotic, scattershot, variable in quality – but never ordinary. When you make your way through Funk Your Head Up for the first time – or the first time after a while away from it – you’re thrown a bit by some recurring motifs. The album’s opening verse – Keith’s typically free-associative mind-dump in ‘MC Champion’ – sounds like it was an early version of verses that appear later, particularly in ‘Poppa Large’: there are references to exercise and fitness, and a section where he dances repeatedly around words that use the sound of the letter "p", like a boxer in training, skipping in the ring then moving over to the punchbag. But as you immerse yourself in his writing, and stop thinking about the record as a collection of tracks, you’re able to hear the songs as a series of journeys, each heading from different places to the same destination, and a new kind of sense unfurls itself.

He’s got a thing about school. There are references to it all over the place, including the bit in ‘Poppa Large’ where he reveals, tellingly, "I’m here to fail and pass" – that he’s not the student looking for the good grade, he’s the teacher, sitting in judgement, dividing the competent from the exceptional, chiding the lazy and weeding out the mediocre. This repeated interrogation of themes isn’t an accident – nor is the frequent appearance of sections where, often in the persona of a character he calls Rhythm X, Keith plays with the sound of syllables or letters, bouncing words containing them around the beats, toying with the feel and not worrying too much about meaning, curiously and investigatively savouring words like a Michelin-starred chef testing a new supplier’s ingredients to establish whether they’re an improvement on what he already uses. (Check that astonishing first verse in ‘Make It Happen’, where he, in effect, publishes instructions on how to listen to his rhymes: "Watch the K: Kool Keith on a swift track/Keith is nice, Keith is dope, Keith is bad, Keith is hype/Now watch the X: X’ll get extra, extra extraordinary/exclusive, exquisite/Examine the X flow: extra exciting/Extremely…") And then there’s the thrill of battle, the album’s unifying thematic undercurrent, signalled at the start of ‘Go 4 Yourz’ when Keith laments that "It’s been a while since I seen a good streetfight," then spends a fair swathe of the rest of the record making up for lost time by starting a few.

Nowhere does this master of the dis excel more than on ‘Pluckin Cards’. If you’d ever wondered how come a rapper as distinctive, prolific and adaptable as the multi-personaed Keith had amassed so few cameo appearances over his quarter-century in rap, ‘Pluckin Cards’ provides some sort of explanation. Not only does he apparently set out to dis almost every one of his New York contemporaries, he makes it oblique, sometimes even almost subliminal. If you were a rapper with a career to tend, you couldn’t risk having Kool Keith guest on your album – he’d probably dis you without you realising. Some have assumed they’re his targets when they weren’t – Freddie Foxxx devoted an entire track to dissing Keith because of the line in ‘Yo Black’ (from the following Ultramagnetic album) "How can you put up a fox against an alligator?" This wasn’t a dis: "I just used to use animals," as Keith told me a few years ago. "I saw him about that, and he talked to me: ‘Yo, you’re dissin’ me’. And I was like, ‘I’ve just used an animal’. People were probably telling him, ‘He writes clever, he writes slick, I know he must be saying something about you’. But I never said nothing about him. I used it as my own phrase. I didn’t even feel that part about it when I wrote that. I used me as the alligator, to a fox. It was just a personal comparison. He took it as me talking about him. That’s like, if I said something like, ‘I’m the letter X but I hate the Z’, people might say, ‘Oh, you dissin’ Jay-Z!’ People got really out of hand."

Some of Keith’s targets in ‘Pluckin Cards’ are clear: you can’t say a line like "Monie and Nikki are just bullcrap" without the intent being somewhat obvious. Maybe Kool Mo Dee’s views on Keith are less to do with his score-keeping than his subjective reaction to this song, and the lines, "Twinkle, twinkle, twinkle little star/behind those glasses I know who you are," and the following thoughts that dismiss and disparage someone who has an apparent obsession with battling a rapper referred to only as "James". Keith’s obviously talking about Mo Dee and his on-wax feud with LL Cool J(ames), though it’s not like he’s taking sides, dismissing the latter as "chickenfeed". (And as far as Mo Dee is concerned, he was big enough to include LL in his book – the fact that he ends up one place behind the author is surely mere coincidence.) There are swipes at Salt’n’Pepa and digs at X-Clan, but it’s the barbs thrown at De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest that seem strangest ("You’re three feet and sinking/The tribes are lost and everyone’s breath stinkin’"), not least because Critical Beatdown was perhaps the key formative influence on 3 Feet High & Rising. ("I think the only people that we looked to for a blueprint were the Ultramagnetic MCs," Pos of De La Soul told me in eight years ago, discussing the making of 3 Feet High…. "They were very different as well, how they rhymed, but they still had more harder-edged beats than what we were presenting.")

Fairly or not, Keith – who was careful not to take aim at the Jungle Brothers – felt Tribe, De La and even X-Clan were diluting rap’s raw essence with what he later described as a "neo-soul" sensibility. "I never liked that era of rap that comes and goes – that neo-soul type of sphere," he told me. "I just didn’t like that whole aura. It was like I was just against Native Tongues by myself – the whole aura of that type of rap. I was mad because I thought they didn’t respect what I was doing at that time. They got more centred into that rather than what rap was. It takes away from rap itself – it takes away from the Just Ice. It takes away from the Tricky T. It takes away from Eric B and EPMD." All that said, looking back, he saw ‘Pluckin Cards’ as fun – as the essence of being an emcee. "’Pluckin Cards’ was just raw dissing – a straight-up record, me goin’ against people. It was made more on a humorous level. It was just what I saw. But that was that time."

In the dialogue among fans about what went wrong with Funk Your Head Up, the prime exhibit in the case alleging label interference and incompetence is the curious matter of the ‘Poppa Large’ remix. The single – released on 12" in the US but scarce enough to command prices in excess of 40 quid on eBay to this day – seemed to exemplify how everything that could’ve gone wrong did go wrong during Ultra’s time at Mercury. Clearly – the argument runs – way superior to the album version, the remix was underpromoted; an acknowledged hip hop classic, probably one of the greatest singles in the genre’s history, the video for it (Keith in a straitjacket, a cage over his head) exists now only in scratchy VHS home-taped recordings of its infrequent showings on Yo! MTV Raps, and a record that should have catapulted the group into the big time ended up becoming the best example of how luck seemed predisposed to elude them. Again, though, this narrative – by no means unreliable – misses some important points.

The remix of ‘Poppa Large’ is inaccurately labelled: it’s a completely new track, which kind of just happens to follow the structure of the album version and share a set of lyrics. While it was already standard by ’92 for remixes to take original vocal tracks and replace all the music, Da Beatminerz’ overhaul of the sonic bedrock was only half the story. Keith’s vocal is an entirely different take, and has him attacking the lyric in a radically altered manner. The line generally taken down the years by Ultra fans is that the maestro was bored when he laid down the album vocal and, energised by a more vivacious backing track, only put his full effort in to the remix. There is certainly a world of difference between his performances on the two takes, but such a reductive view doesn’t entirely add up: this is still Kool Keith we’re talking about, a rap iconoclast almost constitutionally unable to waste an opportunity for experimentation, and while his quality control hasn’t always been the best, going through the motions was never part of his MO. It’s also worth noting that for that argument to hold water, you’ve got to believe that Ced’s production on the album version is so bad as to have been unable to provoke Keith to shrug off his inertia: and that couldn’t be farther from the truth. It’s one of his best-ever pieces of music, the guitar being more itch than scratch, the two-note, beginning-of-the-bar bass line taken straight from the Talking Heads minimalist funk playbook, the whole confection of drums, squeals, skitters and shivers among the finest slices of instrumental hip hop you’re ever likely to encounter. But, to be fair, if all you’d ever had to go on was the vinyl LP, with all four minutes and 17 seconds of the original ‘Poppa Large’ squeezed in to a circle of plastic less than seven millimetres wide, you might never have been able to hear quite how fine it is.

Listen again, and the two ‘Poppa Large’s are less an original and a remix, and more like two different songs. The lyrics – bar two lines at the end of the second verse, added to the album version due to Keith coming in a bar or two early and needing to find extra rhymes to fill the gap before the second chorus – read the same, say the same, in parts even still sound the same; but the meaning is almost entirely changed by Keith’s performances. On the album, he’s conversational, matter-of-fact, considered: yeah, he’s banging on about how great he is, how superior to other rappers his styles and flows and attitudes are – but he’s talking you through it, explaining. On the remix, he’s full on: as the volume and attack are turned up, the assurance and confidence get amplified, distorted. Claims become boasts; boasts turn into brags; persuasion and explanation give way to megalomania and declamation. On the album, he’s sitting back with a satisfied half-smile, as if he were discussing his approach with an interviewer; on the remix he’s in your face, manic, grinning, shouting – living the lyrics, becoming this new character, this bombastic verbal gymnast Poppa Large, right before your ears. The album is jazz; the remix is punk rock. You can prefer one or the other, but they’re mutually interdependent, indivisible parts of the same unique creative vision. And as a pair, they remain the key to unlocking the mysteries of this flawed but frequently magnificent LP.

Ultramagnetic MCs play Sunday May 27 of ATP’s I’ll Be Your Mirror festival at Alexandra Palace, London. More details here