The song ‘Cinematic’ name-checks Cocteau, Picasso and Warhol in the first lines before confessing, "I was never there, I only read the book, I only saw the film, I only dreamed the dream… until you and me". So there, in, like, verse one, you’ve got high art, a dip into wilful bathos, and then a giddy swoop back up to lofty romance. It’s clever and it’s heart-felt and it’s a ride. Such winning melodrama resides in most of Cardiff-based Anthony Reynolds’ songs: they stand out, alone, above. They’re like giraffes in a world of grubs.

Jack – his alma mater – were one of Britain’s most underrated bands in the mid-to-late 90s. Usually compared to The Bad Seeds or Tindersticks (basically because they weren’t strangers to suit-jackets and violins), they had swagger and poise. Despite glowing reviews and a support tour with Suede they never quite caught on: too inclined towards the romantic and artistic, perhaps, for the pragmatic, Blair-ite era, where to be a lad was considered commendable. As Blur’s Mockney mannerisms and Oasis’ salt-of-the-earth blokery flourished, they were deemed too European, too well-read, ambitious, strange. Not indie-spindly enough. It was evident on all their records that they wanted to be musically huge while meaning something, and of course England loathes those who don’t pretend to have their feet planted firmly on the ground.

As former Jack vocalist Reynolds releases his vast, thirty-track Best Of double album, that band’s songs included still resound and roar with wit, wordplay and the wonderful arrangements of chief musician Matthew Scott. Selections from their albums Pioneer Soundtracks, The Jazz Age and (the ‘difficult’ farewell album of 2002) The End Of The Way It’s Always Been pine and prickle with fire and yearning. At their best, Jack combined the cerebral and the physical to a thrilling degree. The adrenalin of ‘Wintercomessummer’, the sexual charge of ‘White Jazz’ (for me, their pinnacle) and the love-under-a-microscope passion of ‘My World Versus Your World’ are several cuts above most game blowhards of the era and, were they to emanate from a new band today, would be eulogised to the skies. ‘Yuka’s Life’, too, is a beautiful thing. (‘Steaming’ and ‘Nico’s Children’ are sadly absent). It’s a pity that final ‘experimental’ album remains relatively overlooked here (though there’s a lovely live version (Paris, 2002) of ‘Maybe My Love Doesn’t Answer Anything In You Anymore’), but hunt it down for yourself and marvel at its fusion of clarity and confusion: the human condition.

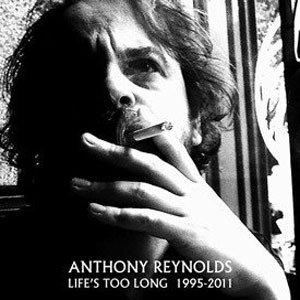

Since the band’s demise, Reynolds has carved a niche for himself as one of Britain’s most undervalued singers and has been known to put on theatre tributes to everyone from Sigmund Freud to himself. Get past the comical-lovable levels of narcissism (one wonders if this package really needs over a dozen pictures of its author more than it needs a lyric sheet) and the work shines. Whether collaborating with Momus or the reclusive writer Colin Wilson (in a summit meeting of cult outsiders), he never knowingly shoots for less than galaxies. The songs continue to glorify and romanticise underdogs, losers, self-pity and, in one of his best solo works, from his very fine true-return-to-form 2007 album British Ballads, ‘The Disappointed’. Influenced by the literature of Bukowski and the Fantes, by Bowie and Sylvian, and by the artists he’s in recent years written well-received biographies about – Leonard Cohen, The Walker Brothers, Jeff Buckley – his gigantic voice reaches, against all odds, the epic quality for which the arrangements strain. There may be too many overblown funereal ballads on the second disc here, but ‘Io Bevo (I Drink)’ (co-written and produced by Gianluca Maria Sorace) flares with mischief ("I used to be somebody…I drink because God is dead") and insight. Its opening couplet bears comparison with any you could name: "I drink because Keith Richards does and Madonna don’t, but should / I drink not to forget but to recall my childhood". ‘Winterpollen’ (co-written and produced by Richard Bell, once – full disclosure – of my old 90s duo Scalaland) takes a subtler, David Gates/Bread direction. Cuts from the album Neu York show a Kraut-Kunst road half-travelled. Everywhere, there’s a refusal to settle for the mundane, the OK, the quite good. It’s all or nothing, or nothing.

Little wonder the rest of Europe – artier, sexier – embraces this artist with more warmth than bad-in-bed Blighty does. At his own cost, Reynolds has always been impractically blind to the expedient benefits of fitting in, of downsizing to deliver, rubbing along with mediocrity, displaying false modesty, kowtowing to the herd-mentality. We have here a bona-fide provocateur, a gamer Gainsbourg, a Welsh Aznavour, a cut-price Cale, and would do well to realise it. Fortunately life is long – an arduous, unforgiving, distressing trek through heartache, frustration, the crushing of dreams and existential angst, as these louche, literate songs testify – so it’s never too late.