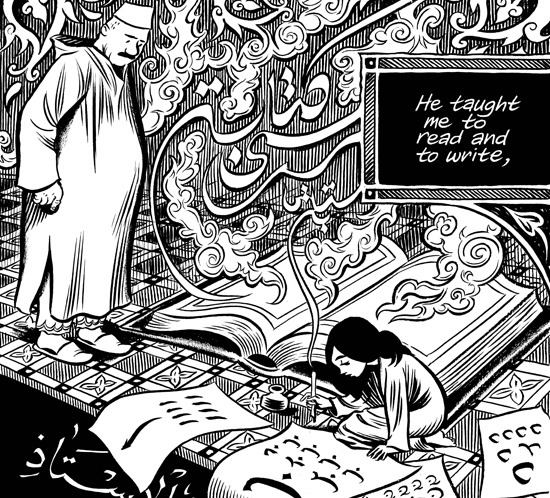

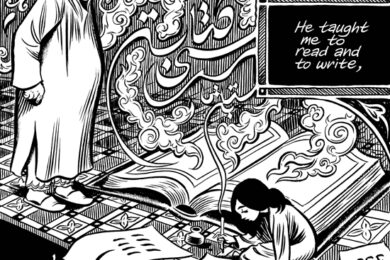

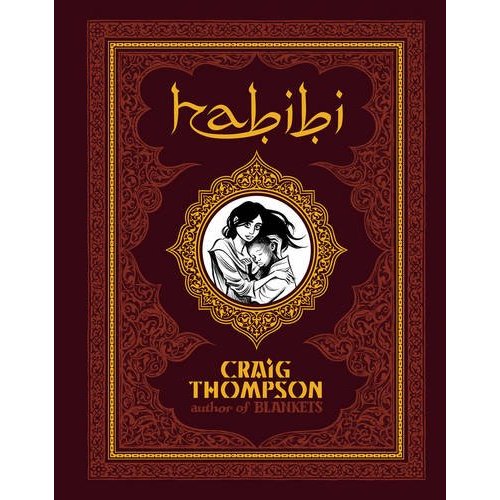

Published last September, Habibi (Arabic, meaning ‘my beloved’) is Craig Thompson’s fourth graphic novel and his masterwork. A breathtaking setpiece of captivating artwork and imagery, inspired by the natural flow and idiosyncrasy of the Arabic language and the decorative ornamentation and beauty of Islamic architecture and design, the story itself is a timeless fictional fairytale.

The book addresses western Islamophobia by exploring the similarities between the three monotheistic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism. But more importantly, the story – which follows the relationship between two orphaned slave children, Dodola and Zam – preaches a global message that concerns those of all religions and everyone else in the world.

Along with Joe Sacco’s documentary graphic novels of the last 12 years, Habibi is a game-changing work, possibly the most important graphic novel since the explosion of Alan Moore and Frank Miller’s populist but cerebral super- and anti-hero sagas of the Watchmen, V For Vendetta, The Dark Knight et al of the 1980s.

What’s equally incredible to Habibi itself is how author and artist Craig Thompson arrived at its conception. The son of fundamental Christian parents, Craig’s upbringing was documented in the intensely personal and occasionally harrowing autobiographical graphic novel Blankets (2003).

Craig was born in 1975 in the unexceptional commercial and transportation interchange town of Traverse City, Michigan, in the USA’s parochial Midwest. Looking to start a new life to raise Craig and his younger brother, his parents took the drastic decision to leave their home state.

"They tore up all their roots, abandoned their friends and family and started driving," says Craig. "They said the Lord was leading them and they were waiting for him to deliver them."

The Lord was clearly in one of his prankster moods that day. They may have driven a good 100 miles, but it was in a backwards loop, delivering the pilgrims into Wisconsin – ironically a short hop across Lake Michigan from where Craig was born. The family settled in the countryside of Marathon County in rural Wisconsin, outside of the already remote and isolated town of Marathon (population 1200). Craig’s school bus ride was now an hour each way from the home his parents chose.

"Their perception was that it was as far as you could get from anywhere," says Craig. "They were part of the back-to-nature Jesus freak movement of the ’70s. They went to Wisconsin to start a little hobby farm that was fully self-sufficient – all our food was grown and raised – so along with the conservative Christianity there were a lot of hippy ideals."

But in reality, that idyllic-sounding, Good Life-style upbringing was one of strict Christian fundamentalism. By the time Craig was in senior year at high school, his future career had already been mapped out by the tight-knit church community: to enter the ministry and become a pastor or a missionary.

Published in 2003, his autobiographical Blankets won many comic book industry awards and is rated by the likes of Time magazine as one of the graphic novels to read before you die, along with Art Spiegelman’s seminal Maus. Such a high profile success made the book even harder for Craig’s parents to accept and their reaction to the story was predictable. "It wasn’t good," he says, with enormous understatement, through gritted teeth. It’s clearly still a sore point. "They were both upset."

Following a family get-together, his parents gave him their full critical analysis of Blankets during a six-hour car journey between Minneapolis and Chicago – with Craig trapped in the back seat.

"They’re both still very devout," he says. "For my father it was a personal issue but my mother thought the book was disturbing on a spiritual level and that I was using my talents for the devil."

Up until that second mammoth family road trip, when the subject of his upbringing was broached as a direct result of Blankets, Craig’s only vehicle for communication with his parents had been his comics. He describes the Thompsons as the classic stoic, uncommunicative Midwesterners. And within Blankets, the subtext of a son’s desperate need for his family’s approval – and desire for a dialogue – practically jumps out of the page.

"One of my friends described Blankets as my ‘coming out book’. As in coming out to my parents in terms of my own spirituality. I didn’t think too much about how it would be received. But it was necessary – it was the only way I knew how to communicate to them."

Without Craig taking the enormous risk of publishing Blankets and losing his parents for good, it’s a possibility Habibi would have never seen the light. But instead of disowning their son because of Blankets, the Thompsons took the opposite road.

"Our current relationship is amazingly improved," says Craig, before dropping a bombshell that utterly revises your opinion of unfortunate contemporary Christian intolerance. "Surprisingly they love Habibi. I can’t totally wrap my head around it! They were very excited, proud of me for the book. Their response was that they really appreciated seeing the connection between Christianity and Islam. It dumbfounds me a bit. Perhaps they’re becoming a bit more liberal with age – or maybe this book is not as personal for them. I don’t think I could offend my parents as badly as I did with Blankets."

Habibi has more than a personal slant for Craig and his family life: a seven-year undertaking – twice as long as Blankets took to make, from conception to publishing – it’s a work of private redemption. Craig has long since rejected what he describes as the dogma of Christianity, but he still believes in the teachings of Jesus and the morality therein.

"There are three main teachings," he explains. "The first is that no human can judge another – which certainly doesn’t reflect modern day Christianity. Secondly, that we are all part of divinity. In the gospel of John, Jesus doesn’t claim to be the ‘Son of God’ – he claims to be the Son of Man. He’s not being exclusive about it; we are all the children of God. If you look at yourself and others with that notion, you can only look at each other with respect and love. The third message would be: give away all your wealth. Pretty much implausible for anyone to do in a modern capitalist society – myself included!"

So as well as the teachings of Jesus, are there any specific Bible stories or parables that inspired you when writing Habibi? There’s something very familiar about the character of the fisherman.

Craig Thompson: Bringing up parables right after speaking about Jesus is interesting because Jesus would always speak in parables and would often get upset with his disciples when they wanted them spelled out. Jesus – in a lot of his messages – was deliberately abstract and wanted people to arrive at their own interpretations. I find that inspiring as an artist.

So you want people to draw their own conclusions?

CT: Exactly – as a dialogue. As regards the fisherman, I think it might on some level represent America as a country; naively optimistic – a bumbling character in the middle of an apocalypse!

You also make an interesting parallel between the story of Noah and the flood and the planet’s current deluge of pollution.

CT: I think all those promises in the Bible are very fascinating. Supposedly [after the flood] God promised never to destroy the world with a deluge again. That doesn’t seem to have helped. I also think the covenant between God is kind of strange and hilarious: Abraham’s foreskin somehow representing a symbol of the covenant with God… It’s difficult to wrap your head around. The foreskin is a covenant with God? Uh, what?

The main character Dodola prostitutes herself for food so she and Zam can eat. Is she a metaphor for Eve?

CT: Throughout the ‘Raping Eden’ chapter, I was exploring the idea that if the Garden of Eden has true historical context, regarding mankind’s first fertile crescent with the Tigris and Euphrates, what would have prompted them to extend beyond this ideal geography than just using up their resources? So there’s a real historical context to that story; humans as a population would have been forced to spread because of using up resources. So we do start in some idyllic, Eden-like context, but our own consumption and destruction forces us outside of the garden. In terms of Dodola as Eve, I hadn’t consciously thought of it, but I like it.

Throughout Habibi is the recurring motif of water and its importance, but water also acts as a metaphor for freedom, self-preservation, a haven (the ‘ship of the desert’), a conduit of escape, a giver of hope and ultimately an employer and tool for celebration…

CT: It’s general, instinctual – the preciousness and primal connection. We come from water and need it above all to survive. All my books have water as a character in some form. A lot of it stems from having a father who’s a plumber. Despite the fact that my parents are politically conservative in a lot of ways, my dad always emphasised the preciousness of water – the limited resource that it is – from the earliest age. He was always stingy with water. Above all other resources in the world we had a sense of how limited it was. We always had a clear notion of waste management; that humans produced waste and someone had to deal with it and it has to go somewhere to be processed and dealt with. I think it’s natural that those things emerged in Habibi.

For a book which addresses such major 21st century themes in a moralistic nature, Habibi has received surprisingly mixed reviews. The worst are puritanical, pompous and – especially in the case of the comics industry – smug and downright jealous, while others contained accusations of ‘racism’, ‘Orientalism’ and ‘excessive sexual cruelty’. Typically, Craig is stoic about the minor irritation of some critics failing to see the bigger picture and missing the overall point. He seems genuinely unconcerned.

"Anyone is entitled to their opinion and there’s maybe some nugget of truth in any criticism. In the same way though, I think criticism and critical analysis is as much about the critic themselves as the piece being examined. In the same way we were talking about Jesus and his parables, and how he didn’t want to spell out the answers for his disciples – not to compare myself with Jesus! – so I like open endings in my books. It allows the reader to impose their own experience and interpretation onto it. With Habibi I’ve had readers say that it was either the most hopeful, beautiful ending they’ve ever read, or the most depressing ending they’ve ever read. Which I think is perfect: that people are really creating their own ending for the book. My question [to the critics] would be: haven’t they read through to the ending of the book?"

The main criticism of Habibi has been the accusation that it’s Orientalist [the stereotypical colonial depiction of Middle-Eastern and Arabic mores]. But if anything, Habibi is the opposite of Orientalism. It actively addresses Middle Eastern assumptions, prejudices and Western Islamophobia for a whole new generation, possibly the first – and certainly the most popular – book to do so since Edward Said’s Orientalism was first published in 1978. Deliberately portrayed as a fairytale in a timeless era with no fixed geography, taking the view that Habibi is Orientalist seems to assume that Craig is starting from the point of gritty realism.

"It’s definitely a fairytale," says Craig. "It draws from all kinds of geographies and time periods; it’s not documentary work. The fairytale element is the most crucial: fairytales are full of dark elements and they cross all cultural boundaries. It’s self-aware Orientalism; drawing deliberately from tropes of 1001 Nights. I think a lot of those elements that are in 1001 Nights are intact from Arabic storytelling tradition – some of them are superimposed by Richard Burton or other storytellers. But that storytelling is exploitative – I think it’s fair to say that – in the same way that exploitation cinema is exploitative. I read 1001 Nights and thought it would be fun to play with that genre in the same way you play with superheroes or science fiction or crime noir. But I did become aware of the Orientalist elements of 1001 Nights so I did want to have a deeper reading of all these things."

That deeper reading manifested itself in seven years of research and writing for Craig, from learning Arabic calligraphy to reading the Qur’an. "I savoured the Qur’an for its poetry," says Craig. "I found it very enjoyable to read. It reminds me of the more poetic books of the Bible, in the way it’s written. Also, it’s more concise – I think it was written in the space of about 23 years. It has this concision and flow to it."

Christians who have responded positively to Habibi have noted the similarities between Christianity and Islam – and how those similarities should be celebrated instead of concentrating on the differences. So how did the narrow cracks between the monotheistic religions become gaping chasms resulting in misery, hatred and war?

Craig Thompson: Yeah… maybe it’s Jesus’s fault. He would be the gap.

Hmmm.

CT: I’m teasing. I think those conflicts ultimately have more to do with land. Geography. Proximity. The land of Canaan. If you read the Old Testament, like a foreskin being a symbol of covenant with God is ridiculous, it’s also ridiculous that God would tell early tribal members that land occupied by other people is now theirs. ‘You get it. It’s yours now. Claim it. You have my permission.’ So there are absurd stories and that’s probably where those conflicts originate.

The importance of Jesus in Islam was a revelation for me when I was working on the book. Being the second most important prophet in Islam, having stories of his own in the Qur’an. Mary too, is really the most sacred female in Islam. She’s almost a prophet herself; she has a whole sura [division, or chapter] of the Qur’an based on her.

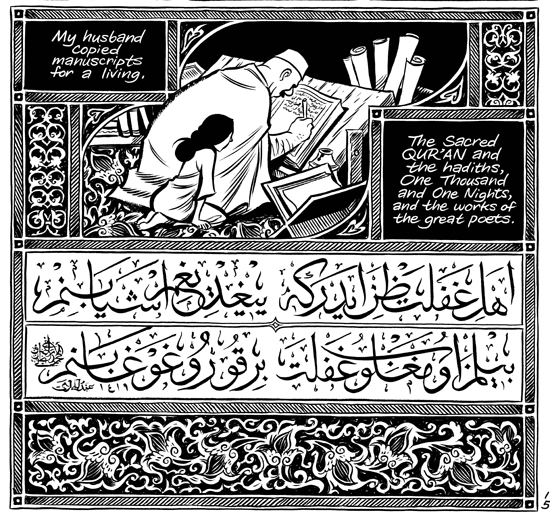

Both were surprises to me when I was reading the Qur’an for the first time. Jesus felt like a crossover figure; the Jewish angle too of course. So I was looking at the connections between all three Abrahamic faiths. At least in Islam, Muhammad is seen as the final revelation, but it’s just a continuation of this message that has been told before by other prophets. The prophet Muhammad is an interesting character because he was illiterate but suddenly recited all this profound poetry of the Qur’an. There’s a great magic to that. He was a humble vessel for something much bigger than himself.

When Habibi‘s main characters of Zam and Dodola are reunited, Zam bears a huge guilt about what he’s done to his body. As a lapsed Christian fundamentalist, do you bear any personal guilt?

CT: I’m full of shame and guilt. These days it has less to do with sexuality maybe because I worked out a lot of that. A lot of that shame and guilt is still a continuation of the American guilt I look at in Habibi. I feel like every morning before I get up for work I have to give myself permission to do something as frivolous and indulgent as making comic books. Part of that’s working class guilt. Part of that’s First World guilt – it’s all these ridiculous things. It’s self-awareness of indulgence of all our forms. As indulgent as they can be, there’s also something very necessary in them. I’m at a point where I can do this for a living so I’m always struggling with this permission slip for myself. Is it OK to do what I’m doing as an adult?

Other than the Qur’an, which writers or books influenced Habibi?

CT: A History Of God by Karen Armstrong and Power Politics by Arundhati Roy. I’m less inspired by her fiction like God Of Small Things but more by her activist work. Also Kahlil Gibran who wrote The Prophet. He merged Arabic and Islamic culture with Christian culture. Like William Blake he worked in both text and visuals, but unlike Blake I think there’s something more readable and sensual about his drawings and poetry.

If you had been born into fundamental Islam as opposed to Christianity do you think you would still be practising?

CT: I think I would have latched onto Sufism… Of all the faiths I’m more interested in the esoteric takes: Kabbalah, Narcisscism, Sufism.

There were different artistic impulses in early societies. Did your own experiences of sexual molestation as documented in Blankets inform the sexual abuse in Habibi?

CT: I’ve always wanted to do a book about sexual trauma. Even though I was molested as a child I never found that as damaging to myself as much as the rape of someone very close to me. I had a couple of people very close to me who were victims of rape. So I did experience a second hand trauma around that in the same way as Zam does. My experience was less severe and not as traumatic or violent as what my friends had gone through. Carrying that awareness with me while I was coming into my own sexuality – and also struggling with a lot of religious dogma around sexuality – it’s something I’ve always thought about processing and wanting to put into a book. It wasn’t until I was working on Habibi that I thought the main character was like me: a second-hand victim of sexual trauma. Who imposed abuse on himself…

Habibi is published by Faber And Faber. Craig Thompson will be signing copies at the following locations:

Friday 20th January, 6pm at Forbidden Planet, 179 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JR.

Saturday 21st January, 5pm at Gosh Comics, 1 Berwick St, London, W1F 0DR.

Monday 23rd January, 7pm at St. Albans Centre, London, EC1N 7AB. A COMICA event – see Comica Festival

Tuesday 24th January, 6pm at Mega City Comics, 18 Inverness St, London, NW1 7HJ