Lioness: Hidden Treasures is an appropriately muted set, with Mark Ronson and Salaam Remi producing an honourable and moving tribute to the Amy Winehouse. In it, Winehouse sings her words, and those of others, to convey her hopes and dreams for a happier future that would never arrive. Early recordings of an 18-year old star-in-the-making hold tragic poignance – Winehouse unwitting, the listener knowing better.

Reading the NME‘s track-by-track review of Lioness: Hidden Treasures, there was one sentence that stood out. Describing ‘Like Smoke’, Dan Martin observed: “It works. Despite it necessarily feeling like she’s not completely on there.” And with that, in passing, the NME stumbled on a sinister undertow. An eerie unease pervades this album – the impression of a sonic hologram of a girl who is now, sadly, elsewhere. Charity fundraising for the Amy Winehouse foundation notwithstanding, there’s something a little tackily strike-while-the-iron-is-hot about the timing of this release, and Winehouse would surely not have made that much-anticipated comeback with what amounts to a covers album. Tabloid interest in the release, and the potential of Winehouse keeping Simon Cowell off the Christmas No.1 spot, feels unpleasantly ironic given their morbid and exploitative fascination with her Blake’n’drugs’n’booze’n’bonkin’ while she was alive.

Commenting on the experience of watching video records of Marilyn Monroe, John Foxx said “made of light and electricity, she talks dances, sings, smiles, yet she has been dead for forty years. She is dust – yet she lives on.” Here, Winehouse feels more the girl of “light and electricity” than the bonny drug-free / Blake-free version the curators put forward. Is it with Monroe in this electronic nowhere that Winehouse is to exist for the next forty-odd years? Probably. With this in mind, ‘Like Smoke”s refrain: "Like smoke, I hung around in the unbalance" assumes a haunting new significance. Ironically, Salaam Remi’s decision to leave the majority of these recordings stripped back was, presumably, for the intention of revealing the real Amy Winehouse.

All told, it’s not until she actually speaks, enthusing over Donny Hathaway in the closing ten seconds of Hathaway cover, ‘A Song For You’, that she becomes fully ‘real’, and even then it is a glimpse of something, and someone, lost. On the evidence of her final performance in Serbia, much of the star had been eroded by five years of drug and alcohol abuse, anorexia and fame. You could argue that Lioness erodes yet more of her, digitalising Winehouse into a state of translucence, a little more of her soul set in glass.

The effect can be partly attributed to Lioness’ benign editorialisation of her legend. Perhaps to counter the cruelly biased image of Winehouse as a trashy lush, Lioness presents a one-sided depiction of the beehived firebrand – industrious, bushy-tailed, classy and classicist. Ever so slightly, ever so uncannily, it’s not the ‘Lioness’ we knew; now tamed.

You can hear this in Winehouse’s part in the Nas-featuring original, ‘Like Smoke’, amounts to eight lines and a scat-riffed melody, rendering it a Nas tune ft. Amy. A sampled Amy; a none more dead-sounding Amy. The Back To Black demos, ‘Wake Up Alone’ and ‘Tears Dry’ are, without Ronson’s production, neither as vibrant or vivid, whereas Remi has developed the formerly acoustic ‘Best Friend, Yeah’ (a Frank-era b-side), turning it into the type of cutesy lounge-jazz Corrine Bailey Rae does.

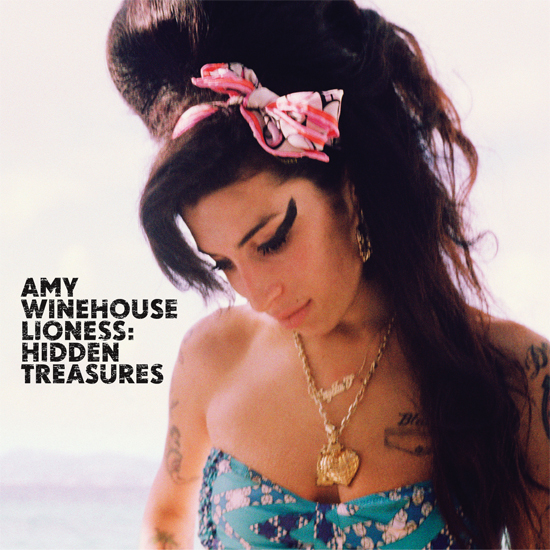

It talks like Amy, it walks like Amy, but you can’t shake the feeling that what we’re listening to is a ghost, a digital one. It’s as if Winehouse has been reanimated to be put through her paces, puppet-like, with a plastered New Boring smile on her face. Taking into consideration the album cover – Amy looking all demure and Benetton-bright – together with the tranquilised Back To Black tracks and squeaky-clean girl group covers, it occurs that never before, not even on the pre-strife Frank, has Winehouse been portrayed as so impassive. What defined her as an artist artist was how she subverted soul – modernised it, personalised it, grungified it, her fuck-me-pumps schtick making relatable the untouchable Motown. All her good work in dismantling the barriers soul erected between her and the audience – her candour, her ‘realness’ – are undone with the distancing effect Lioness’ myth-making brings. The grit, the gutter and the passions of a stormy life have been airbrushed out in the retelling, denying her fighting spirit and the nuanced complexities of a one-of-a-kind pop personality, so deadening the most out-and-out alive star of the millennium. The only treasure hidden here is Winehouse, her true self obscured.