Upon arriving at the Truman Brewery’s ten-day long exhibition of the photography and design of pirate-turned-legit radio station Rinse FM and its long running associate FWD>>, one of the first things you’re faced with is a timeline. Detailing the station’s near-seventeen year history, it begins in 1994 with Geeneus and Slimzee setting up an illegal transmitter with the help of a young Wiley (amongst others) and broadcasting the first Rinse show – comprised entirely of jungle – from the kitchen of an East London tower block. It ends in 2011 with the release of one of this year’s most successful pop albums, On A Mission by Rinse artist Katy B (with Geeneus on main production duties). In between it tracks the rise and fall of UK garage and the origins of Ms. Dynamite, and garage’s evolution into grime, triggering the ascent to superstardom of one Dizzee Rascal.

It’s immediately striking, because it visually demonstrates a fact that’s become increasingly evident over the last few years. Although the station is typically, and rightly, associated with pioneering movements in underground music – the stark sub-bass experiments of early dubstep, the sheer visceral energy of grime, the gradual evolution of funky into a distinct UK strain of percussive, bass-heavy house – the pop landscape of today would look dramatically different without Rinse. Many artists currently making waves in the charts have their origins in the station, either directly in the case of Katy B, Wiley, Dynamite, Dizzee, or indirectly, thanks to the monstrous influence of garage and grime on a generation of pop producers and stars.

Not that they’re likely to show any sign of self-congratulation or arrogance. Rinse Presents: A Visual Retrospective, based in Brick Lane until 22nd August, gathers together artwork and photography from the last ten years of its existence, over the course of its relationship with seminal club night FWD>> and label Tempa. In keeping with the station’s quietly hard-working, quietly forward-thinking ethic, its visual identity has remained more or less constant throughout the last decade. That’s thanks largely to design studio’s Give Up Art’s consistent involvement since 2001. Formed by Stuart and Emma Hammersley, they designed the artwork for the Tempa label – the founding imprint for a gradually emerging dubstep sound – since it began, before getting involved with Rinse. In 2005 they started collaborating with photographer Shaun Bloodworth, when they asked him to take a photo for the cover of the very first Dubstep Allstars compilation for Tempa, and since have worked closely with one another.

It’s the interaction between them that’s given Rinse, FWD>> and Tempa such a striking, intertwined visual aesthetic. Give Up Art’s designs are defined by stark contrasts and hard edges: all flat blocks of colour and multiple interacting typefaces, their great skill is that they manage to look busy without ever feeling messy. Placed alongside Bloodworth’s darker photography, both in the context of this week’s exhibition and on posters and album art, the overall effect is one of balance. His photos neatly capture – but more than that, probably helped to define – the gloomy urban images that spring to mind when discussing especially dubstep.

It’s become journalistic cliché by now to discuss that genre in terms of mood and physical space: ‘cavernous’, ‘low-light’, ‘evocative of concrete, tower blocks and the suburban sprawl’, etc. When experienced in the right environment, through Plastic People’s Funktion One or a similarly immersive soundsystem, it certainly matches those associations perfectly; try listening to early Digital Mystikz at high volume without feeling physically oppressed by its almost unnerving lack of surface detail. But during its formative years, for people picking up on the genre from outside its London crucible (and orbital outposts in Bristol and Leeds), listening through shitty headphones or on home speakers would unlikely have had quite the same psychic impact. So it’s tempting to suspect that Bloodworth’s photos for the Dubstep Allstars series, of producers and DJs in multi-storey car parks, train stations, crumbling council blocks, the pitch-black dancefloor at FWD>>, were at least partially responsible for implanting dubstep’s spectral resonance in the minds of listeners across the UK – and eventually worldwide.

One of the pleasures of the exhibition – bright design and murkier photography shown in striking contrast against whitewashed walls – is in watching the reach of Bloodworth’s photography move further from Rinse’s London base as the music it pioneered gradually went global. His earlier shots feel close-to-home: a still-teenage Skream radiating an intense calm in a packed Leeds Subdub night (which became the cover art for his 2006 debut album); a close-up on Benga, the bottom half of his face lost in favour of cheeky eyes and a huge afro. But from around 2008 onwards, there’s a marked shift in the borders: Glaswegian Rustie, his small frame practically swallowed up by the concrete walls around him; Holland’s Martyn, dressed all in black in front of metal shutters. At around the same time, friendships began to form and solidify between Kode9’s Hyperdub label and LA’s Low End Theory hip-hop collective, culminating in a legendary back-to-back session between Kode9 and Flying Lotus on Rinse FM. Since then a permanent creative conduit has opened between the two cities, so it’s appropriate that the exhibition’s back room is taken up by a series of portraits of LA producers in various places around their home city. A huge close up of Flying Lotus is particularly imposing, almond eyes staring outward with a thoughtful intensity appropriate to the mind-expanding psychedelia of his music. These global cross-pollinations were collected on the 2009 Bleep.com compilation North South East West, where photos of twelve producers accompanied a track from each, highlighting the increasing reach of a London-grown sound.

And as Rinse’s homegrown talent has invaded wider public consciousness, the scale of Give Up and Bloodworth’s collaborative designs has grown to fit. Early A5 fliers for FWD>> and FWD>> vs. Rinse nights are tiny scraps compared to the sprawling blue boards advertising more recent raves – although tellingly, the names adorning them have barely changed over the last five or six years. And since Plastic People was ‘renovated’ last year and given a raft of extra security measures after the council’s attempts to shut the venue down, images of FWD>> nights from years gone by have acquired an almost mythic status. One of the most familiar, of that single red light above the DJ booth, feels particularly resonant, a reminder of the sheer volume of sub-bass that can pack into such a small room.

Certain recent images have already become iconic. The billboard poster for Katy B’s On A Mission, shot by Michael Labica & Sandrine Dulermo is a familiar sight by now, peering outward from bus stops and brick walls (I spot one within a few minutes of leaving the exhibition). But it’s a particularly good example of Give Up’s synthetic approach.

Looking around the exhibition – and, on the opening night, seeing many of the people it features stood around chatting – the overall impression is one of a tight-knit community. It’s a reminder that, though some of the sounds they’ve pioneered have become globetrotting prodigal children, the people involved in FWD>>, Rinse and Tempa have been tirelessly working away in the underground for years. You don’t collaborate with such a passion for such a long time without gaining a sense of perspective. As a newly legal community FM station, last year they ran Rinse Academy broadcasting, production and DJ classes for 14-19 year olds from Tower Hamlets. The importance of a multicultural, genuinely open-minded organisation like Rinse remaining intrinsically involved with the local community it originally came from is hard to overstate, especially given the events of the last week, where the government’s standard Big Society rhetoric has been all too quick to condemn the anger of an entire section of society as ‘mindless criminality’.

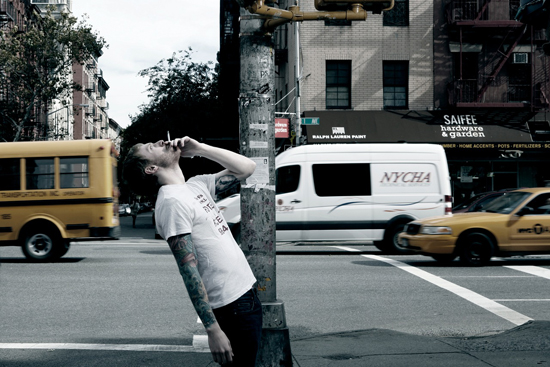

One of Bloodworth’s pictures in particular hangs in the mind for hours after leaving; it’s of Drew Lustman, aka FaltyDL, on the streets of his native New York. Shot in profile, he’s stood up, fag in mouth, leaning so far backward to stare into the sky that he appears on the verge of falling over. The vertigo it induces – body poised between falling forward and backwards, eyes permanently fixed above – couldn’t be a better visual metaphor for his tracks, with their fluid approach to rhythm and daydreamy compositional logic. Like Lustman’s music, the photo itself seems to bubble with its own lopsided sense of funk.

Rinse Presents: A Visual Retrospective – The Work Of Shaun Bloodworth & Give Up Art is at the Truman Brewery Gallery, Shop 14, Hanbury Street, London E2, until 22nd August

FaltyDL photo and Benga/Coki artwork copyright Shaun Bloodworth/Give Up Art 2009