For the last 30 years or so, goth has been the most durable of musical genres. Loved and ridiculed in equal measure, in its refusal to die it has come to resemble any number of vampire movies where the antagonist simply cannot be stopped despite all manner of stakes, garlic and crucifixes.

Yet bizarrely, as it came to mutate over the decades to cross-pollinate with any number of other genres – techno, industrial and metal have all felt the chill hand of goth resting on their shoulders – several of its key players have come to reject the genre like a parent disinheriting an errant child. The Sisters Of Mercy’s Andrew Eldritch will flee from the word with the haste of a bloodsucker making its way back to its coffin before the first rays of the rising sun, while The Cure’s Robert Smith is probably too cuddly to qualify as one despite a following that suggests otherwise.

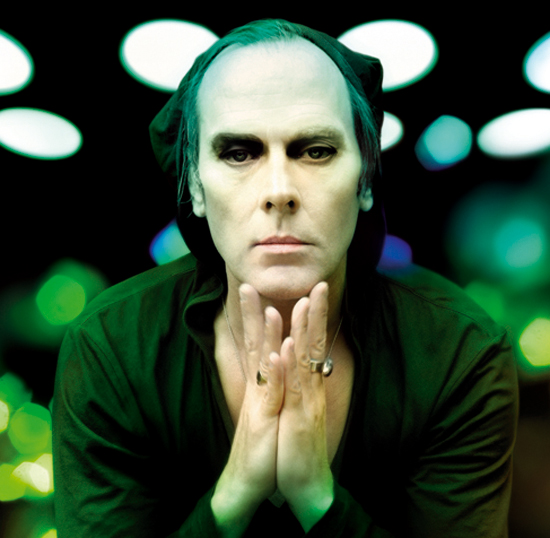

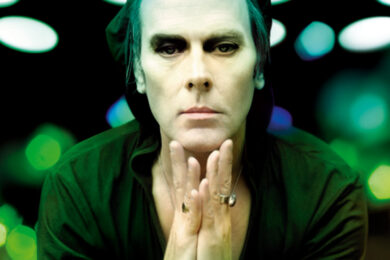

Not so Peter Murphy. The erstwhile Bauhaus vocalist – sharp of cheek and pouting of lip – is only to happy to admit to his part in goth’s formation. Combining sacrilegious and blasphemous subject matter with S&M imagery and a high sense of camp and drama, Bauhaus were one of the first bands to use punk as a launchpad to somewhere else. Their brief reign of terror lasted less than five years but the imprint they left behind is still visible to this very day.

Now based in Istanbul, Murphy has just released his ninth solo album entitled, er… Ninth. Soon to be touring the States, Murphy returns to Europe after the summer, just in time for those long evenings to start drawing in…

From your vantage point of a lifetime of experience, how do you view the younger version of yourself who was just starting out in Bauhaus?

Peter Murphy: Well, with all modesty, when I think back, when we started writing songs in that mobile classroom I knew that I’d made it already. I remember everything because I have an elephant’s memory, and my memories of our farewell show in ’83 [at Hammersmith Palais] are particularly vivid and quite personal, in a sense. Having burnt our fires around the world, I was burnt out, really.

Can you remember what the catalyst was that moved you into music?

PM: From early on, I would whistle. I was more vocal than intellectual at school. I remember always whistling on that dreary walk to school, and there was music everywhere in my Catholic school. But there was music at home, too – more vocal music in a sense, but what really grabbed me was when I watched cheesy television shows like The Golden Shot and they’d always have these visiting stars singing a song here and there. And I used to think, ‘I can do that!’ I don’t know where that came from, but when I was at a concert I always knew that I’d rather be onstage than being down in the audience.

But there was pivotal moment when I was about 14, and we were driving home from seeing relatives. It was night time and I was nodding off on the back seat with my head in my arms, and I just shot up with a great sense of urgency and said, ‘I’m going to be a singer!’ And that was that. They just turned round and said, ‘Right. Go back to sleep.’

How important was the high drama of Catholicism, such as Masses, to the development of Bauhaus stage act?

PM: Tangentially, [guitarist] Daniel Ash and I were the Catholics and the other two [bassist David J and drummer Kevin Haskins] were the miserable, selfish Church of England heathens. When we first started touring, Daniel and I would stay in a bed and breakfast and their parents got them hotels. It was really pathetic. Daniel and I brought the psychodrama to the band, and I would exorcise a lot of that repressed psychodrama that had been left over from Catholicism.

Personally, I used to really enjoy Mass and the hymns and there was a great contemplation of the Anti-Christ. I really enjoyed it but I also wanted a shag, which is why I went into a band, I guess.

My passion, really – which came out in the first album, In The Flat Field – was escaping the flat fields of the mundane; the escape from the working class ghetto of the ‘jobs for life’ mentally and its forced ignorance. That reflected in the Church’s idea of hierarchical supremacy where the priests would say, ‘Listen to me. We mediate between you and God; you just get on with it.’ There was a lot of that that came out in the music.

How big an influence was reggae on the development of Bauhaus’s music?

PM: Massive. We were listening to toasting music all the time, and David brought in a lot of bass lines that were very lead riffs. You can see how those basslines really formed the basis of the music, especially on Mask. We were more aligned to The Clash than anything else that was going around. The Cure and those people really solidified what became goth, I suppose. We had no idea how to play reggae, but that was to our advantage because we expanded on that. It was successful on a very cult, underground level and that was very appropriate because our music was never going to be mainstream. It was seminal music. It was brilliant in its originality.

You’ve said before that Bauhaus left unfinished business behind and you’ve since had two reunions that have ended in a split. Does that leave you with a sense of regret?

PM: It was like an abortion every time. It wasn’t meant to go on. I felt personally very frustrated because I was getting all the accolades and not the band, and so I stopped doing interviews so the journalists could focus on the band as whole. Those unresolved problems came to bear again every time we got together. It was great while it lasted but I think that I’ve got more energy than all of them put together. They can’t keep up with me, to be honest.

Dali’s Car, your post-Bauhaus project with Japan’s Mick Karn, seems to have fallen between the cracks of musical history. How do you think that it should be remembered?

PM: We’ve got a four-track EP coming in October which was made in the final months of Mick’s life. That will honour his memory. But it was right that the album was almost transparent, and it was one of those albums that you would find and not seek out.

When I listen to it, it’s very obtuse; it’s very odd. It was very much opposed to what we’d done before, and that’s why I loved it and working with Mick. It’s very depressive to go and work with something that you feel very uncomfortable with, and it was necessary for all the hordes that thought I was some kind of homoerotic spider to hear this esoteric existentialist type of music. Mick was very comfortable with it because he’d come from this very foppish, Gentlemen Take Polaroids type of band – very mannered music.

It was great when we got together to work last August after God knows how many years, and he showed great respect towards me and likewise me to him. In effect, this is Mick’s final work.

Does the new EP pick up where you left off, or has Dali’s Car moved elsewhere?

PM: You just had to plug in Mick, and he’d sound like he’d sound. He showed me this idea of a song that he wanted me to work on and he kind of apologetically said, ‘Look, it’s kind of pop’ and I said, ‘Yeah, OK, Mick – just show me the song.’ And it didn’t sound pop, that’s for sure! It was totally original. But it’s one of those pairings of opposites that’s just wonderful really. It carries that energy of… let’s call it ‘transcendence’. In a way, the act of making that music [on the album] overcame any personal differences and the music just made itself. That alone is a success.

With Dali’s Car, it was a downer the first time round. The second time round was a joy. Mick was dying, for God’s sake, and for me it was a pastoral gesture.

Given Mick’s condition, was there a feeling of working against the clock?

PM: No. Mick was very present in the now despite receiving all his treatments in hospital and all that rubbish and it gave him a sense of vitality, so that was great. Mick was very grateful and also very witty, he was hilarious. It was a really worthwhile thing to do. The only thing he mentioned about death… he said quite resignedly was, ‘It’s my time but I didn’t see myself going ahead of everybody else.’

Has the ‘Godfather of Goth’ tag been something that’s bothered you, or have you come to embrace it?

PM: No, it doesn’t bother me. As long as they’re talking about me, that’s OK. And it’s totally true! [Laughs]

Well, you’ve still got the cheekbones, haven’t you? And you’ve never had a Fat Elvis period, have you?

PM: Of course, darling! Well, I’ve got a bit of a gut but even my gut is beautiful. It’s marvellous.

How do you view your legacy?

PM: I don’t. I think I do a bit and a lot of people tell me about it and I say, ‘Yes, I know that – shut up’, because I’m carrying on here. I see myself as 3,400 years old going on 17. I think I’m like a jester or a magician. I’m what Bowie should have been, and what lots of people want to be, and I don’t really care. I’m a Jim Morrison, a Frank Sinatra, a little bit Scarlett O’Hara. I’m a myriad of colours. My hero is Muhammad Ali. I duck and I dive and I’m too fast to catch and I’ll always be pretty. [Laughs]

You recently made a cameo appearance in The Twilight Saga: Eclipse as the vampire, The Cold One…

PM: Have you seen it?

No, it’s something that my goddaughters are into…

PM: Oh, check it out. My 21 seconds [in the film] is worth seeing. It’s me again! It’s a wry wink to those who know.

So you didn’t roll your eyes when you were approached to play the part?

PM: No, I thought, ‘It’s about bloody time.’ [Laughs]

So you were happy with the recognition?

PM: Of course, darling! That whole franchise is due to me.

Do you reckon?

PM: Of course, sweetie. What about The Hunger?

You’ve just released your new album, Ninth. What is it that compels you to make keeping music?

PM: I can’t do anything else, sweetie. What am I going to do? You can’t see me walking around digging holes, darling. I mean, I could do it, but it would be a waste.

You’ve gone for a very streamlined rock sound on the new album.

PM: Well, I wanted to strip it all down and go for the eyeballs and say, ‘Look, this is where it’s at.’ We recorded it in seven days. You don’t have to spend three years in the studio, and we hammered it out brilliantly. There’s a lot of rock swagger in it and it has the whole gamut of what I do.

Do you feel that you’re still learning from all the possibilities that music has to offer?

PM: Oh yes. I’ve still got loads of things in my head that I want to do. You’ve got to strategise it, because if you hit people with something really left-field, it will throw you off-track. The thing that I have in my head will require a large audience and my wife will choreograph a theatrical element for my music. It’ll take a couple of years to get this together and I’ll put out another album first. During that time I’m going to get into the world of theatrical sponsorship and see if I can get some funding that way. I’ll know where things are in a year or two.