Read part one of An Eastern Spring here

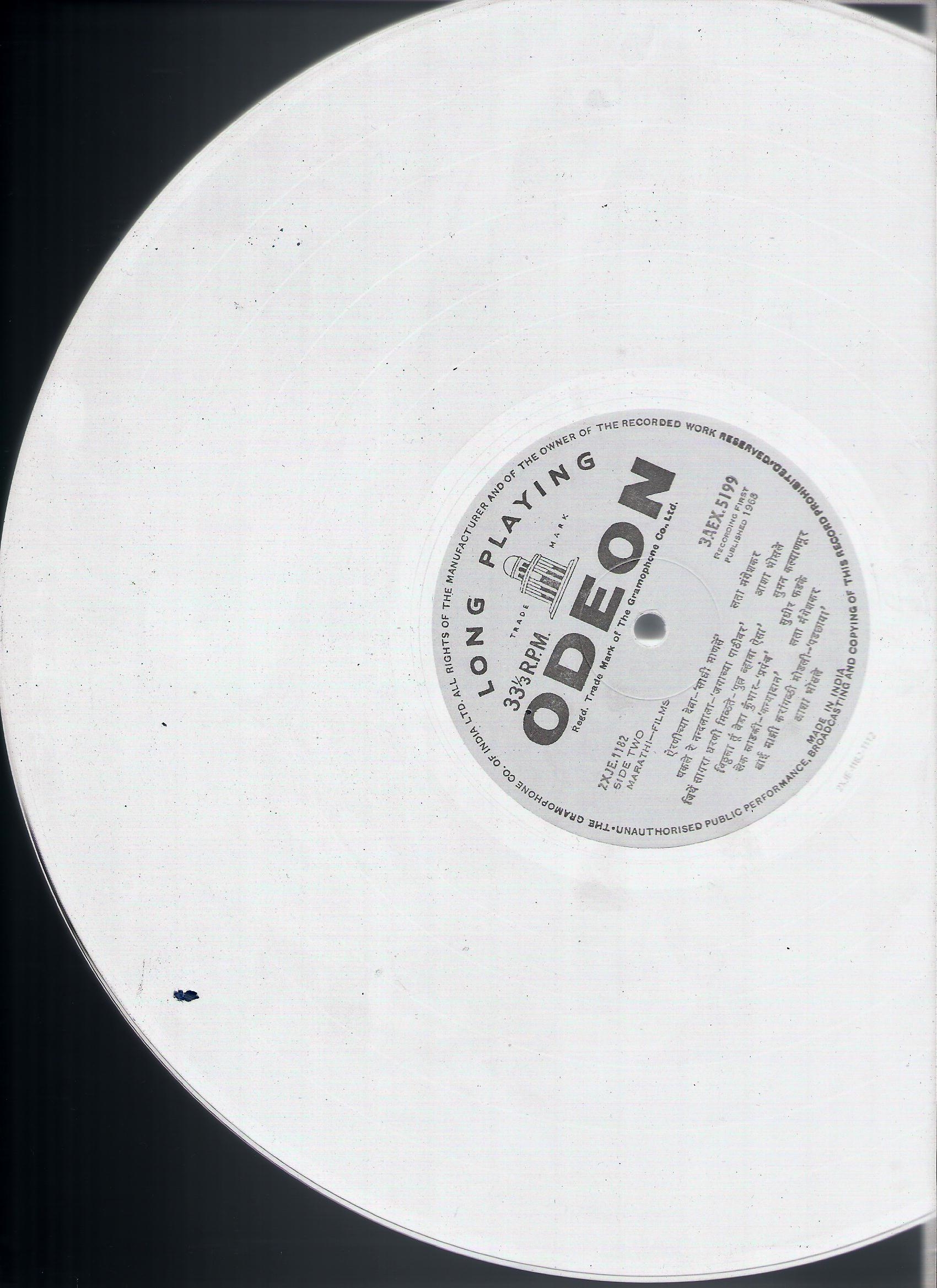

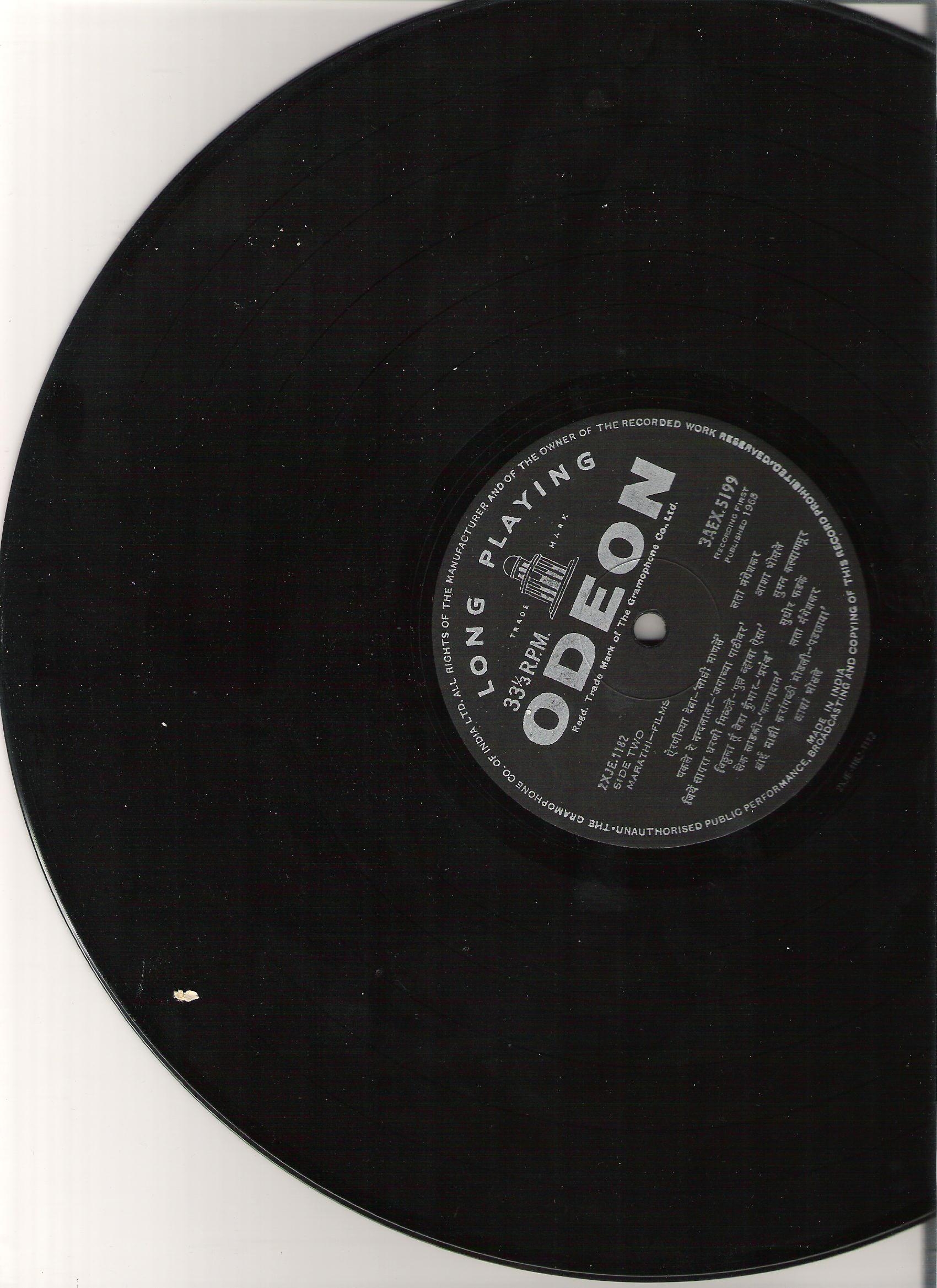

2009-2010. Living in the house I hid in as a teenager I listen to this music in the same rooms I did 30 years ago and the air is thick with the past, spirits this and that side of death. The other room, the front room, is where my dad would listen to music, pint of homebrew in hand, his own thoughts inaccessible to me, his emotional involvement clear whenever I strayed in’n’out of there. Nigh on 30 years after I first heard it, and a good half-century-plus since these songs were composed and sung, I’m listening to a volume of songs called Marathi Chitrapaat Sangeet Volume 1. Most of these songs my dad had on various tapes patiently collated, now committed to bin-liners in the loft. And whilst these songs made my dad feel at home abroad in his new home, they simply made me in 83 feel strange, odd, aware that my own alienation from ALL cultures wasn’t a result of coincidence but down to it being encoded in my cells helixes. Melodies I couldn’t explain, rhythms without time conjured by the all-powerful multi-tracked voice above the drone. Another Hrydnath/Lata gem, another 1000 year old libretto by the Saint Naneshwar who translated the Gita into street-level Marathi from Sanskrit and that has the good sense to know that God is a perfume, and his stink is everywhere.

Listen to ‘Avachita Parimalu’ by Pt Hridaynath Mangeshkar

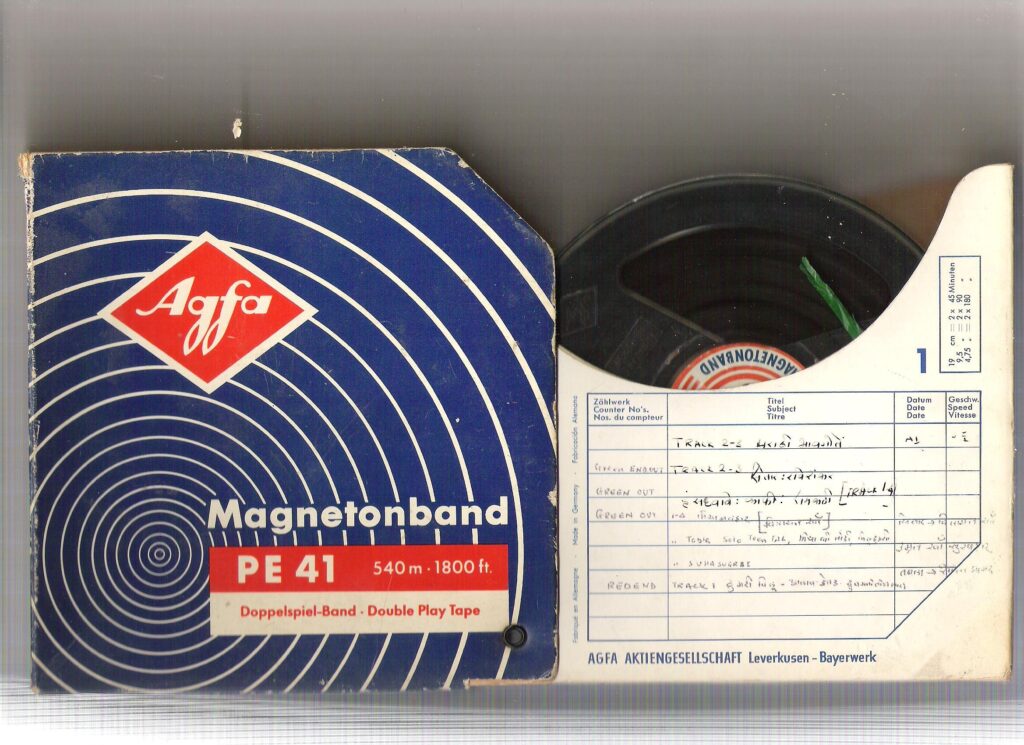

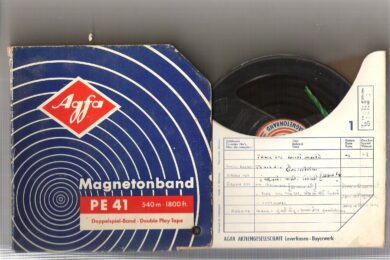

Screens off if you can bear to be reminded of pure sound, and the pure vision that can come from it. Format matters. I listen to these songs on vinyl and cassette but initially I heard them from a reel-to-reel my dad had bought over from Mumbai, on reels he recorded from his elder brothers’ & friends’ vinyl in India (the mic would occasionally be hooked up in Cov too and our voices recorded, now lost is a version of ‘Where Have All The Flowers Gone’, surreptitiously recorded by my dad and sung by me in the bath aged three). That degenerated sound, the signal-loss from all that MOVING of this music from one format to another, is both an essential part of the immersion for me, laceratingly reminscent of those old days, even before the song starts. Some HMV Indian vinyl replaced Nipper the dog with a cobra (particularly on the classical/raga stuff that was an even bigger obsession for me and my dad than the film stuff), heavy shellac relics of the ‘benefits’ of empire, only accessible to that empire’s subjects after the Raj retreated.

If we’ve gone from objects that feel weightily full of sound to the dull convenient emptiness of data sprayed on discs or burned to hard-drives, then at least don’t let your eye be distracted. Resist Stockhausen’s correct insistence that ‘the eyes dominate the ears in our time’, try and give the above emanation of sound some weight the only place you can anymore, inside your head.

Plus, you don’t need to know what those lyrics mean. The reductive lie of translation might blind you to your pre-lingual reaction which will be more accurate, honest, and open to an unpinned wonder. These were the first songs that hinted to me that maybe sound was time-travel, that only music made time a dimension that could be stepped through, that maybe the future could be thousands of years old. Like all Marathi songs, there’s a linguistic umbilicus back to Sanskrit clearer than in Hindi or Urdu songs – Marathi as a language shares more ancient Sanskrit words and constructions than Hindi. This, in conjunction with Maharashtra’s ancient singer-poet tradition, the fact our saints (Eknath, Gnaneshwar, Tukaram) communicated through poetry almost exclusively, and the strict rules of subject-matter and shape that govern Marathi song has always given golden-age (for me, 40s-60s) Marathi films a different intent and intrigue – for me entirely separate from Bollywood, entirely at odds with Bollywood’s gleeful self-exploitation at home and abroad (entirely fittingly Marathi film is dwarfed by Bollywood now). Whether devotional or ritualistic (Abhangs/ Kheertans), or romantic or plain randy (Lavani), ancient Marathi song’s sense of purpose is clear, even if at our remove its exact place is enchantingly nebulous and nomadic. Totally clear lyrics about love’s confusion of the senses.

"The main subject matter of the Lavani is the love between man and woman in various forms. Married wife’s menstruation, sexual union between husband and Wife, their love, soldier’s amorous exploits, the wife’s bidding farewell to the husband who is going to join the war, pangs of separation, adulterous love – the intensity of adulterous passion, childbirth: these are all the different themes of the Lavani. The Lavani poet out-steps the limits of social decency and control when it comes to the depiction of sexual passion." K. Ayyappapanicker, Sahitya Akademi

Inevitable that when these ancient traditions, devotional and indecent, take themselves to the pictures in the 40s and 50s the results are pumped with independent pride, as well as touched with a new melodic. In comparison to the coy/whoreish borrowed fantasy/chasteness of Bollywood, Marathi ‘Shringarik Lavani’ (literally ‘titillating songs’) are genuinely erotic, useless to the repressed west, but entirely linked in with folk and classical-music traditions that are ancient, that link songs to times of the day and everyday activity, songs that understand how music must find a space in life to resonate, not pompously just boss reality into submission. No accident that in the new upwardly-mobile globalised Mumbai, marathi songs aren’t played much on the radio, spurned for their ‘downmarket’ feel.

A fact exploited by the scum in the Maharashtrian far-right as a further erosion of Marathi (i.e Hindu not Muslim) ‘values’. Precisely why we should still be listening, cos one listen to Marathi music and you can hear Islamic music’s influence, just as you can in all Indian music. The Quawalli & Ghazal infiltrate every twist and turn of Marathi song, even if it’s held up by scum like Bal Thackeray as a relic of a proud hindu-nationalist past. Religious tolerance, openess to other cultures and creeds has an older deeper more magical history than Marathi fascism, and is reasserted everytime you hear Marathi song. The finest Marathi poets assert that everyone is human, that all faiths are paths to the same thing, that caste is a tyranny. The fact that songs based on their writings are being used by these bastards on the Mumbai-right to justify faith-hate boggles the mind and misses the truth of all music. Musicians have to share to survive.

I’m glad the market’s over. Gives me a static set of songs to renew on. The further I’ve got into this music over the years the more I’ve realised that I have to shed what pop’s taught me, I even have to shed what pop-writers have taught me, and start again with this music. Re-teach myself that music isn’t simply ‘all I care about’, or ‘my whole life maaan’: remember that for whole chunks of the world music is as necessary every day as food, light, and shelter. Not just something you couldn’t manage without, but something that makes you a human, makes you able to carry on being a human. Starts you from the dawn and gets you through. The entire hindu ‘faith'(always a misnomer seeing as much hindu philosophy is entirely atheistic) is a song passed on. We have no bible. No book. The Vedas, the Gita, the Upanishads – all orally passed on poetry, turned into song to make it memorable to the illiterate. You don’t have to believe in god. You just have to believe in the song. So what I find in these soundtracks is the exact opposite to a soundtrack, I hear not the backing to life, but life itself. My life. Everybody’s life. Our separate lives.

1978-1982. Move to Ernsford Grange, Coventry. Make friends. Catch bus to and from school with sister, latchkey kids. Read a lot. House down the road, ‘the punk house’, occasionally skinheads snarling & spitting my way, fear of god locked inside forever, chip on shoulder growing. One close close white friend, play everywhere with him, like all my intense friendships it ends in desertion and/or horror. Late 78 he asks me out to play post-cherryade Sunday afternoon. Make it down the corner, his other friends waiting with a waterbomb and a few well-placed punches and a few new words they’ve learned like paki and nignog and wog and blackie (and the neatly conflated ‘blackistani’). Wail and it makes them hit harder. Teaches me something very important. Don’t trust them, ever. And never talk about the way you feel. In retrospect at least that early brush with racism was flagrant and outré and joyfully cruel and easy to respond to once I got my breath back – learned early that if you start getting wordy back, outfox those English (who seek to deny your Englishness) with your precocious command of their lingo, people tend to shut the fuck up, steer clear. Preferable in a way to the middle-class ‘tolerance’ I endure the rest of my life in the suburbs, that inclusion/exclusion so woolly and gaseous it’s impossible to windmill against. Crucially by now all kinds of music is giving me worlds to hide in even as I imagine cameras swooping around me, pop, hip-hop, what happens after the charts, finger on condenser-mic pause button, whether it’s Annie Nightingale or Peelie. The Indian music that still thrills me conjures worlds that to my parents are entirely familiar, part of their upbringing, worlds that to me are startlingly alien, that make me an alien by dint of being tied to them by birth, from birth. Not a situation that makes me unhappy, not a grievance but a wedge between me and the world that I’m glad to cultivate and nurture. Precocious little fuck also lost now in classical music both western and eastern and, always always, my parents songs cos these are melodies and rhythms as blue and black as me, sounds I can’t get anywhere else. 82 final move. The house I now live in.

The texture of rotting celluloid captured on quarter-inch tape stuffed in suitcases & scrawled in indecipherable characters – 30 years later it all still sounds like it’s happening now, still speaks for daydream or a hope that’s ageless and immortal. 30 years later I spend much of 2010 being unable to write about rock music. Thank the last minute of Bo Diddley’s ‘Bo Diddley’ on a Chess compilation I want to review but that actually paralyses me from writing. Go listen to those drums. Comic voodoo heat untouched since and unencumbered by a coffin of pedals or any trick other than the unique joy of Bo himself. So how can I now write about the beats here

without hearing Pram and Moondog and a whole host of later discoveries hinted at? When it’s nothing to do with them but the sounds of a bellows and an ironmonger, less high-art than a village life I never knew? I still read too many descriptions of oriental or African music practically gleeful in their realisation that ‘Hey this sounds like [insert hip/laughable yet digestible western ref.point]’. Perhaps it would be more useful to not only look deeper at the context and reasons behind eastern musics (at least to drag us away from the increasingly dwindling returns of the white/black conversation that is western pop) but also to, with some humility (foreign to most western perceptions) admit we can’t just neuter this music with false lineages, by peripheralising it as an obscure point on maps we’re over familiar with. We’ve got to stop seeing so much ‘foreign’ music as accidental simulacra of the western forms we’re familiar with but love it for the entirely alien things it can teach us, less a superficial re-cycling of its sounds than an internal absorbing of its structural oddity, the functions it serves in its native communities. We’ve got to rob our response of the easy options of amusement or our smug glow of geopolitical self-improvement and simply listen. We’ve got to see beyond the datedness & chuckle-icious cultural differences, contextualise our understanding/knowledge more but actually decontextualise our listening, be more open to the music by being humble before it rather than arrogantly correcting it (or cheesily loving its incorrectness).

Impossible of course, but I’m bored with what’s possible. I crave our overthrow, our invasion, our surrender. We need to explore modes of listening rather than simply jazzing on the ‘foreign-ness’ of this other music. Because there’s an infinity of it to explore and it’s the only way out for us. Or for some of us, the only way back in. Where was I? Oh yeah, 83. See? Time travel.