"Tools are not necessary for diamond searching. A good way to find them is to walk up and down, looking for diamonds on the ground". – Information On Digging For Diamonds

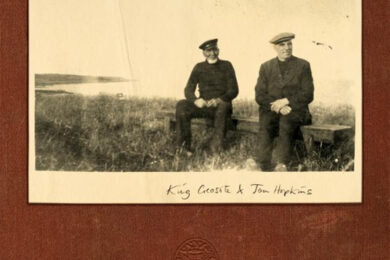

Some parts of Fife do not want to be found. It therefore requires one train and four buses to cover the sixty-three mile distance between my home (in the Central Highlands) and King Creosote (in the East Neuk of Fife). We rendezvous for a guided tour of the geographically remote yet culturally precious stretch of land which is the star of Diamond Mine: a sublime long-player and labour of love between Fife singer-songwriter KC (aka Fence boss Kenny Anderson) and London electronic composer Jon Hopkins (fresh from his ambient union with Brian Eno).

We trace the coast through the fishing villages whose gull cries, harbour chimes and mythologies populate the album: from Anstruther (chief site of the Fence Collective’s annual Homegame festival), through Cellardyke (home of DIY empire Fence Records) and on to Crail (official residence of King Creosote).

In the fifteenth century, another monarch – King James II of Scotland – described Crail as ‘a fringe of gold, on a beggar’s mantle’. These days, it is apparently known as ‘Scotland’s east coast Riviera’. The Neuk inspires the romantic in all of us – except, perhaps, KC himself.

Hopkins’ love affair with the area started around 2005, and the album’s warm textures and glimmering details serve to reflect his responses and memories. "For me, this record is a romanticised version of Fife," he offers. "A lot of it’s about my first experience of going there – about my first Homegame, when I fell totally in love with the place, and with Fence. It’s a bit like my dream version of life.

"Of course every time I go there there’s a festival happening and it’s not a very realistic way of looking at things,’ Hopkins acknowledges. ‘I’m sure Fife has a lot of other stuff going on, but this record is not about that. It’s like the way Paris appears in Amélie. And I don’t have a problem with that at all."

Anderson is more pragmatic about his East Neuk day-to-day. "I don’t know if I have a very traditional take on what this area is," he says over a pub lunch. "I get annoyed about that new mini-roundabout out there. I appreciate it for other things. There’s somebody that draws chalk circles and question marks round all the dog-shit on castle walk. I’m on the side of the Crail chalk-marker."

While Diamond Mine circumscribes tidemarks and monuments, so too does it excavate over 20 years of Anderson’s musical treasures, oral traditions and artefacts. Field recordings of seabirds and spring tides lap over a song about his neighbour (‘John Taylor’s Month Away’). You can eavesdrop on KC and his daughter discussing their family’s medical history in a local tearoom (‘First Watch’) and witness roadside bust-ups with his brothers, replete with aimless engine roars (‘Running on Fumes’).

King Creosote & Jon Hopkins ‘Diamond Mine’ by DominoRecordCoIn this context, Hopkins operates as archivist and re-animator: he has scrutinised KC’s back-catalogue; mined several long-forgotten gems (‘Your Own Spell’; ‘Bubble’); fused them with recent compositions (‘Bats in the Attic’); insisted on stunning new vocal renditions; and invested in them an exquisite breadth of melody, harmony and instrumentation.

He breathes new meaning and life into the songs – revives them as a whole body of work – and yet never overpowers Anderson. ‘When you’ve got a voice that beautiful, all you want to do is support it,’ Hopkins offers. ‘I always let the vocals lead.’

"I don’t know what Jon hears in what I’m singing about, and I don’t know what images he gets from it, but he does get something," Anderson muses. "And what he does with it can be absolutely heart-breaking. [JH also produced KC’s 2007 album, Bombshell.] I feel really privileged that he’s chosen me as someone to work with."

While Hopkins is eager to articulate his romantic attachment to the area, and KC’s lyrics identify landmarks like Kilrenny Church and Roome Bay beach, both parties are wary of being perceived as geographically twee. "I hope we’re not called fucking whale song music", shudders Hopkins; "I hope nobody thinks we’re like the Fife version of Cornish Sea Shanties", echoes Anderson.

Hopkins’ aural manipulations and electronic alchemy mean that such accusations are unlikely – many clips are so processed they’re barely identifiable – but the album’s incidental (and accidental) sounds are nonetheless embedded in Fife: from bicycle wheels and rattling sails, to the consciously Scottish vowels bade of Brighton-based backing vocalist Lisa Elle (aka Lindley-Jones).

Even car indicators were recorded in situ: in Anderson’s car, in the Kilrenny Churchyard. These vehicular clicks deliver the nervous rhythm on ‘Running on Fumes’.

"I’d brought this little field recorder up to Fife," recalls Hopkins. "I took it with me when we went to Kilrenny Church tearooms – we got there really early to get the best cakes," he laughs. "So while we were waiting for it to open, I scrabbled down this hillside toward this stream that I wanted to tape, but I just kept getting all the car engine sounds from people arriving for the church tea instead. That’s what you can hear on "Running on Fumes."’

The church also plays a pivotal role on the heart-stopping ‘Bats in the Attic’. It looms over Anderson as he comes to terms with life passing ("I counted 18 on my pulse as Kilrenny Church struck three for three o’ clock") and it resonates in one of the record’s most devastating musical milestones – that is, the piano chord of b-flat minor, which bursts through the surface noise of ‘Bats…’ like a kirk bell pealing out of the blue.

There are many such lovely abstract tributes to the East Neuk on Diamond Mine. ‘John Taylor’s Month Away’ – a psalm about a local fisherman and the dread of continually being elsewhere – positions KC at the swing-park in Roome Bay beach (he takes us there: it is lonely and beautiful), and the song’s quiet thought gives Hopkins scope to conjure the lure and lull of the coast.

"The instrumental section of ‘John Taylor’s Month Away’ sums up so much about the idea that I had for the album," explains Hopkins. "You know, that we’re not in any rush to tell the story, whatever that story is. Normally I’d have a section lasting this long, or I wouldn’t allow so much space, but why not give this album all the care and attention it needs? That’s the concept at the end of this song, just before it fades away: why not revisit some of those vocal harmonies, have them wash over you." And they do: like tides and tears.

As we wind back up to his house from the seafront, Anderson downplays the importance of his native signposts. "Even though Roome Bay beach is mentioned, I don’t think this is a Crail record, or even a Fife record, at all," he says. "It’s very visual music, but I don’t visualise cycling through Kilrenny when I hear it. You don’t need to stand on that new mini roundabout to get it. It’s not about the place so much as the state that you’re in, and what you’ve either been through, or need to be through."

He is right, of course, but that’s not to detract from the album’s nigh-on supernatural powers of transportation. "I’d do little bits on Diamond Mine around other work," Hopkins remembers. "I’d do bits on tour, so I’d be sitting in LA in my hotel room, or travelling on the train though Europe, but it never mattered where I was. I’d stick my headphones on, and I’d be in Fife again."

It also plays havoc with notions of time: it taps into our collective histories and our hopes that are yet to be broken. It lasts five minutes, and also a lifetime. "Yeah, I’m obsessed with the idea that you can be hypnotised by music," enthuses Hopkins. "There are a few weird low frequencies and sounds that repeat, or disappear into echo, or go on for longer than they should on the record. It all kind of has the effect of telling your brain to slow down; and to give the music your full attention."

"That’s what I really like about the album," agrees Anderson from his kitchen table – in his welcoming, turreted, patched-up dwelling that stretches back generations, and looks out to sea. "You listen to it – you really concentrate on what Jon’s done, even just on that first track – and before you know it, the bath’s run cold.

"For me, every record I make is going to be my next attempt at Talk Talk’s Spirit of Eden", KC continues. "And I never will make it, because it’s untouchable. But I honestly think that Jon has captured something of it with Diamond Mine. When he let me hear it I was like, ‘you know what? I really don’t know what to do next’, because, in some ways, I’m at that peak. I don’t know where to go from here."

King Creosote packs me into his car, and we drive through coastal Fife in the night-time. The road-trip is sound-tracked by 80s synth-pop and floodlit by lasers emanating from potato fields.

Anderson insists that this is not the upshot of some localised sorcery; that diamonds do not shine out of the farmland; that every East Neuk evening is not bathed in otherworldly light.

He claims that it is just the practical by-product of a nearby tourist event.

I’m not convinced. You can justify magical things until the sun goes down. This does not make them less extraordinary. It does not make them less enchanting.

King Creosote and Jon Hopkins play London Union Chapel on May 25th