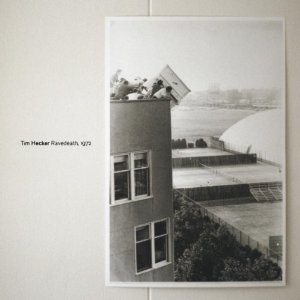

All too often it’s easy to overlook non-musical influences when listening to an album. Given that a great deal of music (and music writing) takes quite a singular approach, avoiding multidisciplinary thought in favour of placing sounds within an established canon, it’s wonderful to occasionally come across a record that’s intensely evocative of the world beyond its self-contained universe. Demdike Stare’s recent Tryptych is a great example, its darkened samplescapes summoning a grey and drizzle-soaked – i.e. uniquely British – vision of the occult, as is the volcanic force that regularly tears through the Arctic crust of Ben Frost’s By The Throat. Tim Hecker’s Ravedeath, 1972 is another, right down to its intensely visual title and demonstrative track names (‘The Piano Drop’; ‘Hatred Of Music’).

On an immediate conceptual level, then, even before the record’s started to spin, Ravedeath, 1972 is intensely preoccupied with mortality and the passing of time. In that sense it sits neatly alongside modern sonic adventurers like Philip Jeck, Raime, Shackleton, King Midas Sound and Demdike Stare, who channel a sort of nameless dread through exploration of the processes of decay and resurrection. In some cases – King Midas Sound, Shackleton – those themes are made manifest, either vocally or by strongly harking back to music in its role as primal release, as means of releasing pent-up tension through physical action. Others, like Demdike Stare and Jeck, are less prescriptive about the themes that run beneath the surface of their music, instead choosing to allow methodology to dictate meaning. Both use ancient, creaking vinyl and a library of esoteric samples to tunnel wormholes in time, opening conduits between past and future and, in Jeck’s case, stretching single moments to the point of eternity. His wonderful An Ark For The Listener, released last year, is a case in point: its opening track ‘Pilot/Dark Blue Night’ extends the final desperate gasp of a sinking ship over eight long minutes, before the blueish glow of its porthole lights finally dissipates beneath the waves.

Indeed, the first record that springs to mind when listening to Ravedeath, 1972 is Jeck’s latest, though aesthetically Hecker explores a region somewhere between that album’s abstract approach and something a little more direct. On the one hand, the twelve instrumentals on this album could easily work as standalone, such is the sheer force with which opener ‘The Piano Drop’ ripples and roars into action, before crumbling away into three part epic ‘In The Fog’. Combined with artwork, track titles and lofty concept, though, it’s a glorious, elegiac meditation on loss and transcendence, uniformly greyscale and melancholy in tone and given to vast, sweeping gestures. Whilst much of it is content to lie languid in clouds of fizzing ambience and drone, when noise hits – and it does – it really hits, with an elemental power matching that of Frost’s By The Throat (unsurprising, given the latter’s involvement in its recording).

Two other major themes make themselves strongly felt throughout, both of which are inseparably linked to one another, and the album as a whole. The first is spirituality – Ravedeath was recorded in the first instance using an organ in an Icelandic church. That instrument’s bombastic resonance and sense of the grandiose generates a sort of secular solemnity, less preoccupied with any single religion than with the fears they all hope to address. The second is Iceland itself; but rather than Iceland the beautiful, touched upon by Mum and Sigur Ros, it’s Iceland the bleak, as a pure and living example of the Earth’s enormous power. Again, in that sense its closest bedfellow is almost certainly Ben Frost’s work, which brims with the same feeling of barely contained feral rage.

In an interview with The Wire towards the end of last year, Sam Shackleton talked to Derek Walmsley about going to see a church organ recital. "It always makes me laugh," he mused, "as if sub-bass was some kind of modern thing. Those guys in the church have been listening to sub-bass for years… [In the past] if you were in the sticks, and you came to the big city for the first time in your life, this must have been mindblowing… Just as if you go to a club the first time and hear a proper soundsystem, it’s something incredible."

There’s certainly something to that notion, something that can’t help but spring to mind when listening to Ravedeath, as ‘Hatred Of Music I’ escalates to a climax so all-encompassing it feels as if the very speakers it’s playing through are about to erupt. Religion has always about gathering people together under shared beliefs, to share experiences, but ostensibly on a level where everyone is equal. The anonymity and depth of electronic music, especially played through a decent soundsystem, often allows it to serve the same purpose. At high volume, Ravedeath, 1972 approaches transcendence, achieved through the overwhelmingly physical resonance of channeling the past through the present.