The only point at which Bill Callahan makes and holds direct eye contact during our admittedly awkward, hour-long conversation is when I mention that I was – and probably wrongly – surprised to read that he’s really into Lil’ Wayne and The-Dream. He looks away from the crook of his puffa jacket-clad elbow to enthuse (well, it’s all relative) about Wayne’s productivity and the life that rips through his every freestyle, no matter how thick the fug of purple drank vapours is that cushions it. Such preconceptions aren’t particularly useful in general, but here, it’s perhaps illustrative of two things. Despite being fourteen albums in the tooth, we still know extraordinarily little about Callahan’s personal life. As Daniel Ross commented in his review on Bill’s last, Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle, it benefited from “a real lack of engaging context” – seemingly no more relationships with high profile indie musicians, and shedding the baggage that came with his former moniker, Smog; his personal life, less significant. For all we know he’s sat at home trawling blogs in search of the first cuts from Tha Carter IV.

On a less flippant, developing note, the thought of him drawing so much satisfaction from the music of a man who arguably doesn’t have a private life, who’s given to making confrontational statements about every aspect of his successes, failures and myriad controversies, seems almost perverse when you consider the closed-off demeanour with which Callahan responds to questions about and interpretations of his music and lyrics. On his forthcoming fourteenth album, Apocalypse, Callahan kills himself off twice. Once at the end of the first side of the record, on ‘Universal Applicant’, where the small boat in which he sails burns when caught by the rescue flare he sends up, and then sinks, him along with it. He imitates a gentle firework popping sound. “The flare burned and fell; the boat burned as well.” And then he chuckles. At the end of the second side, the final song, ‘One Fine Morning’ sees him “ride out with the skeleton crew” for what ostensibly sounds like a funeral for an entire family.

But these aren’t deaths, or any signal of finality, he insists, but rebirths and revelations relating to the other meaning of the record’s title. On ‘America’, he sings “Everyone’s allowed a past they don’t care to mention,” which he may maintain isn’t personal, but seems especially pertinent when it comes to the way in which each of his albums under his own names offers some break with what’s come before: Woke On A Whaleheart took his own name, but handed over arrangement duties to someone else, …Eagle stated that it was “time to put God away,” setting aside another trope that had loomed large in his back catalogue. It’s too early to ascribe any certain significance to Apocalypse, but its sonic trajectory follows on from his statement at the start of …Eagle’s ‘Jim Cain’: “I used to be darker, then I got lighter, then I got dark again.” Apocalypse sees him lightening, even when its prevailing subject matter is endings, rushed and ruined marriages (‘Baby’s Breath’) and standing before crowds imploring them to ask him one last question in order for him to offer up explanations (‘Riding For The Feeling’). This contrariness, to be found from even his first record, is surely what makes him such an enduring songwriter, and a rather frustrating interviewee – particularly considering that as soon as the tape was off, he started to talk about his past with the same comparative gusto he reserved for discussing Weezy.

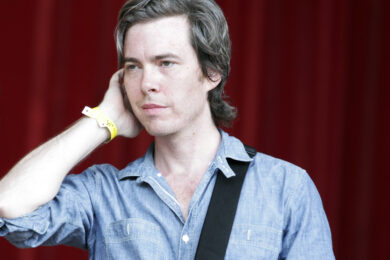

The Quietus met Bill Callahan in a Notting Hill pub, after he read from his book, Letters For Emma Bowlcut, at Rough Trade West.

I cocked up the directions to Rough Trade West and missed the reading. Did it go well?

Bill Callahan: [laughs] Err, yeah. Best reading ever.

How does standing up and reading compare to performing your songs? Do you have a preference?

BC: It’s quite similar. Just because they’re both about delivery of words and I think… It’s probably a world I’m not that familiar with – I don’t do that many readings… and also it seems like people don’t really know how to react to you, because if you go to a show…, but reading is, like…. Well, it’s such a cerebral thing that it’s like… well, what is supposed to happen exactly?

I don’t know about you, but I can’t take everything in if I’m being read to, I have to take it and read it myself.

BC: Yeah, my mind… I can’t follow the story.

In your songs, even if you’re saying hardly any words, your inflections tell the story. I was reading some interviews about the book where you were reluctant to explain certain details. Do you worry about giving too much away in the delivery?

BC: I think it actually really helps; I mean, people have said that to me too. There’s so much about rhythm in this book – it’s not exactly prose, and it’s not exactly verse – and I think it actually helps to hear it aloud. You could read it really fast because it’s a short book, and it means nothing, but [read aloud] it reflects who’s reading it.

When I interviewed you about the book previously, you didn’t want to explain the significance behind “the core” and “the vortex”. Have you heard many interpretations from readers as to what they think they mean?

BC: Erm not really… I mean I’ve got some feedback about it, but not really that stuff. I don’t know.

Do many people come to you with stories about their experiences with your music, or talk about what it means to them?

BC: Not really. People aren’t usually that specific. They say they like things but there’s usually not time or space for them to expand and stuff. So like, sometimes…

When you were writing the novel, did you have concrete meanings and interpretations in mind, or is it more abstract than that?

BC: Yeah, it’s an abstract. It’s like a solidly abstract thing because some things in life are abstract, and some things in life never will be more than that – so it’s supposed to be not entirely specific, because that’s what some parts of life are like.

Can you see yourself writing again in that way?

BC: I don’t know, I mean, I’m gonna write another book, it’ll probably be different. I don’t know… whatever happens. I haven’t really started it, so I don’t know what’s gonna come out or when.

Have you listened to Gil Scott-Heron’s cover of ‘I’m New Here’?

BC: Yeah.

What did you think of it? Did he approach you and ask if he could cover it, did you have any direct contact with him?

BC: His producer Richard Russell – he wrote me a letter, which was really unusual – not an email, an actual letter. It was really out of the blue. He said, "I’m working with Gil Scott-Heron, and he’d like to cover the song." Yeah. [long pause] It was a big surprise.

Are you a particular fan of his?

BC: Yeah. [very long pause] It still kind of seems unreal that it even happened.

Do you get a lot of request from artists to cover your songs?

BC: Well, you don’t really have to ask permission.

Even if they’re recording and releasing it?

BC: Well no, as long as they’re not, you know… doing some weird… if they rearrange it or something, like, radically change it, they’re supposed to ask. But if it’s close to the original, you can cover whoever you want without asking.

I was really struck by how close Gil Scott-Heron’s cover was to the original. It really sticks out on his album.

BC: Yeah.

Getting onto your album, why the oblique announcement, just that outlaw wanted sign?

BC: Yeah, that was just a play on the title of the record. Just like, you know, the crazy people who hand out those leaflets that say, "The end is near!", “end times” people. Supposed to be something like that.

Why Apocalypse?

BC: Erm… Well on the last record, the title was so long that you had to take a deep breath and reserve time to tell someone. This one’s just really easy to say, and people always smile when they see what’s the title. People liked that word for some reason.

To some people apocalypse is the most pessimistic thing they can think of, yet to others people the idea of an apocalypse is like a second coming, it’s almost optimistic. Which is it to you?

BC: Well it has different meanings – THE apocalypse and just apocalypse. The apocalypse is the end of the word, but apocalypse is just a revelation – a revelation can be the end of the world, where you whole world dies and your new world is revealed. It’s not just about the end of the world, it’s about the world we live in.

Even before you listen to the words, just sonically it seems like a journey that edges towards a sort of death/rebirth motif in the last song. By the end it’s incredibly breezy and light, the intonation slow and rewarding patient listening. Can you explain the movement of the record?

BC: Yeah, the first half is dark. All the songs are in darkness, and then there’s the last song on the first side – ‘Universal Applicant’ which has this explosion, it’s like enlightenment. Everything after that, the rest of the record is light. It has a dark side and a light side.

There are people who will relate that dark/light motif back to religious imagery, especially relating to the closing song of Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle. Are you addressing that in any sense?

BC: I mean, I think I try to stay away from religion, it’s so easy… It’s part of culture, but there was light and darkness before religion, so I’m trying to approach it from a pre-religious, or post-religious sort of thought… .

Going back to the instrumentation, in an interview about the last album, you didn’t know if Drag City would let you use such luxurious instrumentation and lots of sessions musicians again. Is that why this record is so much sparser in sound?

BC: Well, I wanted to make a record that was… …Eagle was recorded with a live backing band, then they added strings, and horns and stuff. I wanted this time to have a sort of ensemble, to make it more like a live record with nothing added afterwards. It’s basically the same as the record before it, if I’d gone and added strings and stuff. It’s more I noticed, touring with a cellist, it kinda… [tails off]

It made everything sounded incredibly rich.

BC: I mean, it’s great, but it’s a little limiting because I like it to be possible to change things, and doing that with proper musicians is like their worst nightmare. They’re like rocks, they’re so reliable every night, but then if you want to change… So I just wanted to make something that was more just like a little band playing together.

You can really hear that – this album sounds almost more like it was recorded with a traditional folk band, the violins and flutes especially sound quite rustic and English. What kind of sound were you aiming for?

BC: Err, I would really say it wasn’t based on English [folk] at all. More American jazz and the fiddle is more like something you’d hear in street dance, street bands, that type of thing. And just with using a flute – really I don’t know what’s gonna happen.

What do you mean you don’t know what going to happen? Because you’re not a flautist yourself?

BC: It’s kind of a wildcard type thing. I don’t want to be too comfortable performing the record, and if there’s something like that that I don’t know how to deal with, we’d see what happens, try to make it work.

Is that something you’ve done on past records, try to give yourself obstacles to get over?

BC: Yeah, I try to have a wildcard a lot of the time. Just to keep me on toes.

Reading interviews about the albums you’ve made since recording under your own name, it seems you’ve afforded varying degrees of authority to the people you’ve worked with. Where did the authority lie this time around? How much influence did John Congleton have?

BC: Erm, John had nothing to… he’s just the engineer, he just gets things on tape. He doesn’t have any creative input, except for things like sound. It’s more just my thing this time. The record before this one, I recorded with the band – just the band first, and then the strings were done later. …Whaleheart is the only time where I really just handed over the reins.

In retrospect, how do you feel about having done that?

BC: [long pause] I’ve got a lot of records so… I like to do something different, see what happens. I’d have never come up with that record myself. So it’s good, like, something different. It was good, I’ve learnt a lot. Mostly I like… it’s nice to have a break, that was nice. When I decided I didn’t have to worry about that at all, it was a nice little… I just really just focussed on the audience and singing and stuff. If you do something a lot, it’s nice to just mix it up.

I’m not musical at all, but it kind of struck me listening to the new record that this is less based in melody, a lot of the guitar parts almost seem to lock into a groove more.

BC: On the new record?

Yeah, especially as the songs are quite long, it seems with a fair few of them that your voice that carries it rather than the guitar itself.

BC: I think …Eagle was much more like a trance, like a locked groove thing, with a band and then the strings came and added like, drama or whatever, shifting it. But this record, the new record, I thought it was more dynamic and shifting, because we all just played in a room together live.

Looking at the length of the songs, as a collection, with the exception of ‘Free’s’, they’re longer than anything you’ve done before. Was that intentional – did you want to write longer form songs?

BC: Not really. It just happened.

Whenabouts did you write these songs?

BC: I recorded it in the summer, so I wrote it in about four or five months before the summer.

Do you find people react to you differently now that you record under your own name?

BC: I’ve really noticed nothing. It seemed like a seamless thing to me. Some people still think that Smog was a band, and this is a solo record, but some people never read the album artwork and… I didn’t really notice any difficulty with the transition.

Drag City were reluctant to let you change your recording name – have they since conceded and said you were right?

BC: [laughs] Yeah, they have.

Did it afford you anything to hide behind when you were writing? I read an interview from 10 years ago where the interviewer asked you how much of these songs is autobiographical, and you said 0%. This might be wishful thinking, but it seems as though there’s been a more personal switch in focus since then.

BC: I dunno… writing is, it’s a third … it’s a spirit or something. I just don’t really think of anything as either autobiographical or not autobiographical. Its just writing…

You read an autobiography as a person, but you write it down and it’s like a different entity. It’s like a force or power or something, it’s not really about you and not about people. It’s just something else.

Does it bother you when people try to relate your lyrics back to you?

BC: Yeah – I mean it’s annoying, but it’s what people do.

It’s easy to listen to a song like ‘Riding For The Feeling’, where you’re singing about standing up and wanting people to ask you who you are, and interpret it as you being more open.

BC: I’m prefacing my opening up with the song, you mean?

Not to be so naïve to assume that’s what you’re saying, but I’d say that’s definitely a way of looking at it. Especially with the way the instrumentation as starting dark, and getting lighter – people might try to interpret it as representative of a positive change in your life.

BC: I guess… I don’t really… I am the person who made these songs, but I don’t want to write about my life. It’s supposed to be just stories, that people can hopefully relate to their own lives, not my life.

One of the record’s less introspective-sounding songs is ‘America’. Even though you’re singing about how great it is, there’s almost a sardonic tone to it. Even the way and the amount of times you say "America", it almost doesn’t feel like a real word by the end of it. Is it supposed to be a critical song?

BC: It’s just kind of like a love letter to America. People are always attacking it – literally, but mostly figuratively… People are kind of down on the country just because of the last… since 9/11, really. And it just seems like it’s time for that to stop.

In the last verse of the song, where you start mentioning countries that America has had conflict with, that seems implicitly critical.

BC: Well, it’s supposed to be in the vein of a love relationship. It’s like I say in the song, everyone’s allowed a past they don’t care to mention, so it’s supposed to be like your old lovers, or enemies. It’s actually not critical, it’s saying everyone makes mistakes.

Because obviously you touch on lots of different aspects of the country within the song, I wondered if there’s a novel or a film that is your favourite representation of America, that you read or see, and a recognise as your experience of it?

BC: I think Nelson Algren, that writer – that’s really America to me. He wrote lots of books about New York, street life in the 40s, 50s and things. Never Come Morning – when I read that, that’s like quintessential America to me. But with ‘America’ the song, for some reason that guitar, I was always picturing Apocalypse Now, the movie, with the helicopter, and the bombing. Just the sound of the guitar, it’s like bombing, but softer…

I don’t know why this surprised me, but I read an interview where you said you were really looking forward to albums by Lil’ Wayne and The-Dream – what is it about that sort of music that interests you?

BC: Lil’ Wayne is so productive, and crazy, and something about that really productive nature, it makes the music really alive – not like something that’s been laboured over for two years in the studio. It’s just really fresh and exciting, and kind of disposable since there’s just going to be more and more, and it’s fun to be a music fan for that sort of stuff. It’s almost like they’re doing a newspaper or magazine that comes out every month.

Does the idea of doing something like Kanye’s Good Fridays appeal to you?

BC: I feel like, if I was doing hip hop I could do it… It’s just something about the nature of that music, its freshness, that means it takes in things that are happening at that moment – riffs and stuff, repeated samples. I wish I could release a song a week, but it just takes me too long.

I daresay some of your fans might not be too into that method of releasing, Wayne’s fanbase is probably a fair bit younger than yours on average.

BC: Yeah, they want something new, instead of something good or whatever.

Are you constantly writing, or do you sit down with the intention to write a bunch of songs?

BC: I’m always writing. It just gets smaller and smaller, starting from like a cloud, and then narrowing down the boundaries and stuff.

How would you characterise the mood of Apocalypse, its feel and intention?

BC: It’s very introspective more than… it’s an inward, and also an outward looking, from the inner. I’m seeing a lot of mirrors, it’s like a lot of things – an inward looking thing.

With ‘Free’s’ and ‘One Fine Morning’, which seems to be about people dying and also a new dawn, it struck me that you could interpret it as you putting music to bed, in a way. Is there any sense of finality to this record?

BC: Nah, it’s like every death, it’s a rebirth. That wasn’t really supposed to be about that, that wasn’t the frame to that.

Is there any specific death/rebirth narrative that you were following?

BC: To the album? I haven’t really analysed that song yet, probably the least of them… I don’t know, the people are experiencing some kind of death, and then it becomes the road, you know? It’s like I just picture the dead bodies becoming the tarmac, and then someone else drives over that.

When you’re writing them, do you not have a meaning in mind?

BC: Some songs are more concrete than others, but that song was like, ways of saying something that you know but where you don’t know what you’re saying. You know that someone else is going to receive this information, but you’re not going to know to how to put it into words either. It’s like a beacon, you just look at it, stare at it, but don’t know why. So that song is really like that – not trying to be too specific. Maybe it has like a wider audience when it’s not tied down to one thing.