Bryan Ferry’s studio/office complex, discreetly hidden away in the stretch of London known as Olympia which runs between Kensington and Hammersmith, is a beautiful thing. On arrival I am led by one of his assistants down a corridor lined with large framed photographs from the cover shoots to Stranded and Siren. Not the well-known cover shots themselves, but out-takes. (To a Roxy-ologist like myself this is as thrilling as finding a previously undocumented stone tool would be to an archaeologist). Then I wait in a reception area full of subtle art and Moroccan rugs and a cute dog the size of a saucer. The dog skips up to me, allows itself to be fondled, disappears, then reappears with an even smaller toy dog between its teeth. A phone rings and another assistant says, “Would you like to follow me?” She leads me downstairs, or maybe upstairs, it’s a bit of a maze, and then I shake hands with the sultan of suave.

To my delight she calls him “Mr. Ferry”. He’s always taller than you think. I’m given a cup of tea in a leopard-print mug while Mr. Ferry finishes something (it’s twelve noon), and I sit on a sofa. It’s too yielding, so I move to a firmer sofa, not wishing to be at any more of a psycho-geographical disadvantage than decades of hero-worship necessitate. This room is huge, classily appointed, consisting of various lounge/office/art-lab spaces. I begin memorising the books on the bookshelves but give up because it’s, you know, absolutely everything of any merit.

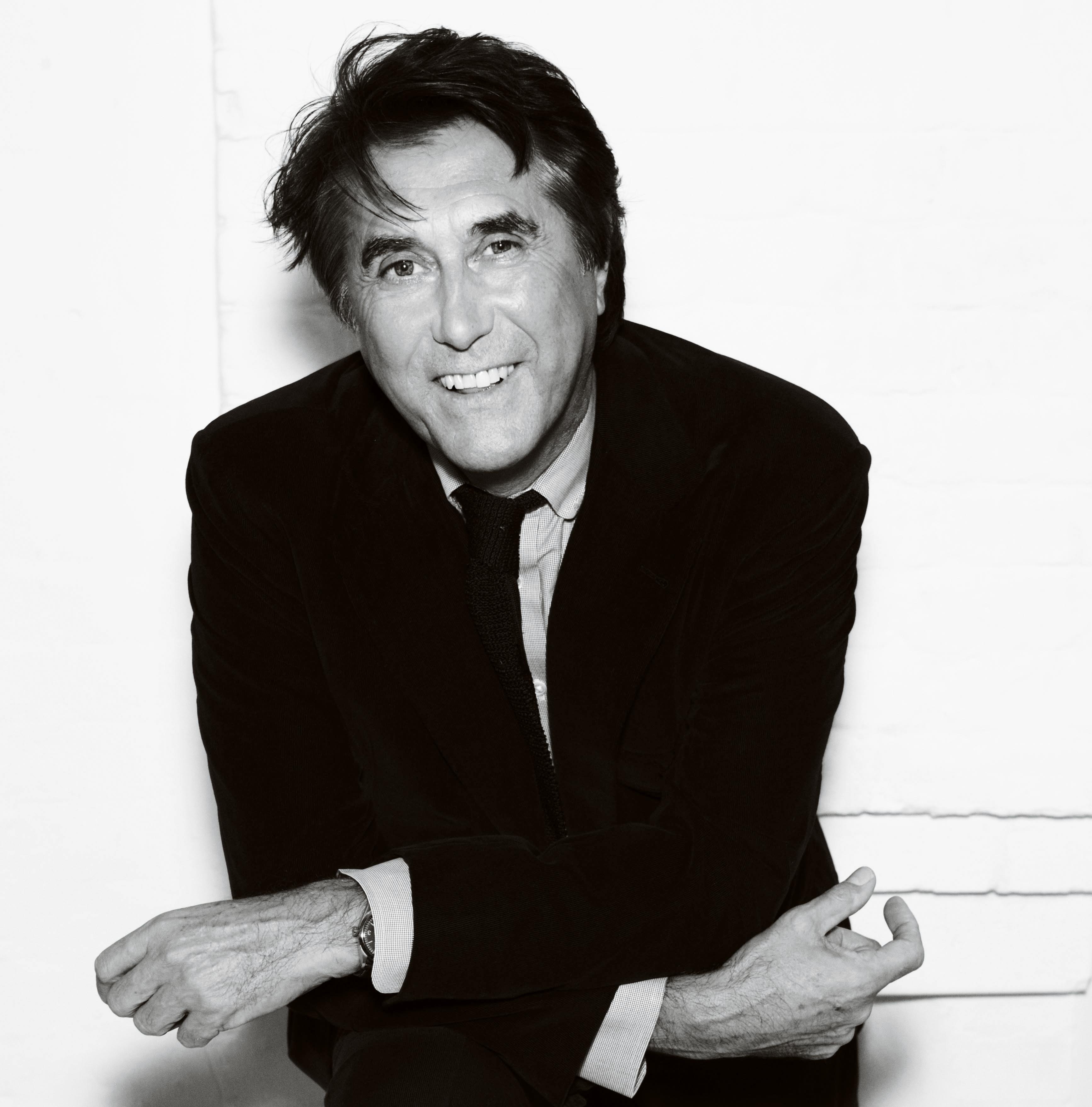

Mr. Ferry comes to join me and produces a microscopic recording device. He asks if I know how to work it. I don’t. He phones a young person, who materialises in front of us within seconds and clicks it on. Mr. Ferry mumbles something to the effect that he’s not mistrusting me, it’s just that someone’s asked him to record himself talking so that bon mots can be compiled. The 65-year-old is both vague – he begins sentences, pauses, trails off, then picks them up again just as you’ve decided it’s time to butt in – and very precise. He’ll say quite unguarded things, but also correct himself on things that seem less dicey. He’s very friendly – the Dirk Bogarde/ David Niven charm is not a myth – and yet in spells there is, undeniably, an hauteur, of which I’d say he was blissfully unaware. Of course, it would be disappointing if there wasn’t.

A few years ago he asked me to write his tour programme. After I’d emailed it over, he phoned up and said he’d sent a car for me. When I got to Olympia he asked if it would be OK to remove a comma. I said, “Sure.” The car then brought me home again.

I ask if he had a wry smile to himself when he decided to call his new album, his best since 1987’s Bete Noire and therefore a work of grace and light and multiple layers and glacial funk, Olympia. Did he foresee that Roxy-Ferry fans would immediately leap to lofty images of Zeus and Greek legend, or that snipers would cite the title of a Leni Riefenstahl film (about which more later), not realising it was named after his postcode?

“Exactly, yes, ha ha.” Just shaking off the flu and having sung frequently of late, he has a game, throaty laugh. “It’s quite fun being next to the Olympia Centre. They’ve had some bizarre events staged there. They sometimes have, what is it, an exhibition of erotica or something. All these pierced people walking around with devil horns on. Ha ha! And the Horse Of The Year show. All sorts of people pass through the area. It’s very unglamorous really, but close to everything. Chelsea, Kensington, the West End, you know. To get a place this close you’d normally have to go to Shoreditch… wherever that is.”

Do I need to explain who he is? How to describe the workings of a hummingbird’s wings? Roxy Music changed the face and curves, the visage and physique, of rock and pop. From their definitively art-school debut album of 1972, the collision of past and future of which still startles, through the Gatsby sighs of Ferry’s gondolas, glam and goddesses period, then the two-year split, then the return with the likes of Manifesto and Avalon (so improbably refined that they shouldn’t exist, can’t exist, but do), Roxy were the ultimate marriage of style and substance: inspiring, influential, intoxicating. More than this, Ferry finessed a solo career, and has since oscillated – but languidly – between covers (or as he prefers, “readymades”) and his own increasingly balmy, textured craft-quirks. To the wrath of a few, this son of a County Durham farmer/miner has never in adult life been poor, or badly-dressed. He’s not what music critics tend to call “authentic”. He’s better than that.

At this stage he is above all the petty niggle and hiss. He should be having retrospectives at the Guggenheim. In truth he should also be above The One Show, but needs must.

You’ve been getting out and about a fair bit lately, doing plenty of promo and surprising TV appearances. In the past you’d have been cagier, guarded your mystique…

“Very much so. The longer you spend on a record the more you feel obliged to promote it. I just want to advertise that it’s out. I suppose in some ways the older you get, the more interest there is, in case it’s your last. And nowadays there are so many things that require that you talk to them; it’s just endless media. In the old days it was just NME and Melody Maker of course, ha ha. And maybe Disc, Record Mirror… As for the Strictly Come Dancing type things, I felt perhaps more confident to deal with those, so I said why not, devil-may-care. Strictly is no worse than Top Of The Pops was. It’s actually better in many ways, better filmed. You just go on and do your song, there’s no awkward ‘chat’, and I love it when you don’t have to do any of that. Even in the days when we did Parkinson and so on, I never did the talking bit, I didn’t feel comfortable squirming about. Now I’d probably say yes.”

The studied ballroom glamour of Strictly was in many ways apropos…

“I suppose so. I didn’t really see it properly. All I knew was there were these flames going in and out of my field of vision. Dancers? Were there? I don’t know. Whatever. I’m being very game. Loose Women was one of the nicest things I did. It was funny. I thought, oh well, this is a lark. And there aren’t any record shops any more, which is slightly worrying. Hugely worrying. It’s very sad. Unless you have a top twenty record, Tesco won’t stock you. I don’t see promoting a record as a ‘sell-out’ though, if that’s what you think.”

It isn’t. Plus, Bryan Ferry just said “Tesco”.

You’ve spent years on this album, as you tend to, almost endlessly polishing tracks and ideas that you’ve kept on file. Would you choose to work like that, or is that just the way it pans out?

“If I was super-organised I’d be quicker, sure, but I find it fascinating. You always work on more than you need, for an album. Well, I do. If you have your own studio it encourages you to keep things lying around. In the old days, working in one studio for one album, you’d lose everything.”

Isn’t there a temptation to procrastinate, to never declare anything finished, to keep painting the same water lilies or Marilyns over and over?

“Yes but that’s quite nice. It means you end up doing things that others wouldn’t be bothered to do. For instance, having three bass players on a track (‘You Can Dance’), which people think is a bit mad. But it sounds great; it’s a great big machine. Like the great leader James Brown always had two drummers, and when I saw him he had two bassists as well. He supported me, believe it or not, at a gig at the…you know…the dinosaur. You know…the Natural History Museum. A kind of corporate show for a bank or something, a few years ago. Maybe two years before he died. And I said, my God, James Brown is supporting me? This is absurd! But it was great, the interaction of musicians was like an orchestra…” He tails off, silently sighs. “Most people can’t be bothered with things like that now…”

I once interviewed James Brown in his dressing room before a show and as I left he insisted I take a bowl of bananas as a gesture of his “love and spirit.” I was too polite to decline and so walked to my seat in the crowd, holding the bowl of bananas throughout the concert.

Bryan Ferry guffaws. “Ha ha, he must have liked you! It’s a shame you didn’t get him to sign each one. You’d have been a very popular banana man.”

I’m taking this in and regrouping when Bryan Ferry says, “I was once in a hotel elevator with Chuck Berry. It was weird because he was so unfriendly. Maybe he was embarrassed because he had this McDonalds brown paper bag; he’d been out to get a hamburger to take back to his room.” (In truth, Mr. Ferry says “McDonald”, not “McDonalds”. I doubt he’s overly familiar with the concept.) “I thought it was rather sad. I was just coming in from a Radio City Music Hall show I’d played in New York, with a towel over my head. And there he was. And we had to go up about twenty floors. So I tried to make conversation, but it was a bit hard. He was hugging his Big Mac and I think was embarrassed that I’d recognised him.”

I…. uh….

“Oh I’ve got better ones! I was in another elevator once with Charlton Heston. And that was in Newcastle. I was also in one with Charles Aznavour, years ago, before I’d met him. We were both looking at the floor and he was whistling; it was funny. I could write a book about elevator meetings. But oh yes, Charlton Heston. In Newcastle! In the hotel by the racecourse, a strange place to see him. I think he was doing a theatre season. It was a tiny, tiny elevator. You’re dying to say, ‘Loved you in Ben-Hur‘ or something, but you know you shouldn’t. And the funny thing was he had a towel on his head too because he’d been jogging.”

Bryan Ferry laughs his head off then says, “So, did you say you like Olympia?”

A week or so previously I said hello to him at his album launch party at a Westminster art gallery. A six-song set close up, champagne, models, an exhibition of Kate Moss photos from the Olympia cover shoot; it was well swanky. I said, “Your best album in ages, if I may say so.” He replied, with a wolfish Max De Winter smile, “You may.” He then bowed – yes, bowed – to my companion. Today he recalls, “I didn’t get to taste the food, though I chose it. By the time I’d sung, it had all gone.”

Olympia, yes. It’s more cohesive than Frantic, more unified in mood and atmosphere. Layers upon layers upon layers. An unabashed return to the classic Ferry themes of yearning for impossible romance and idealised beauty and then yearning some more. And loving this yearning, wallowing in it, relishing it. Preferring the fantasy to reality. A seam he’s profitably mined, usually with exquisite results, since Beauty Queen and Mother Of Pearl. On Olympia the currents and jetstreams and vapour trails are played by his own stunning band (including Nile Rodgers, bassist Marcus Miller, young guitarist Oliver Thompson and twin drummers Andy Newmark and Ferry’s son Tara), plus a stellar guest list of Brian Eno, Phil Manzanera, Andy Mackay, David Gilmour, Jonny Greenwood, Flea, Mani, Scissor Sisters, Groove Armada…

“Part of it’s having a lot of young people around. They were very keen it would be strong-sounding, have a certain edge to it. It’s been a lucky project."

Do your sons foist new music upon you?

“Not at all, no. Perhaps they should. My son Isaac drew in the dance mix people that got involved, because that’s a world I don’t know much about really.”

As a perfectionist auteur, it must be agony for you to let someone remix tracks…

“Not really. I tend to go: oh that’s interesting, how funny that they didn’t use this or that line or element that I thought was fundamental. But I accept it. I’ve made my version, and now they can make theirs. Like someone’s making a movie of your book. I thought they’d play these on the radio, but that’s the only area that’s let us down. I don’t get it. I think there’s an ageist thing with radio in England, sadly. And there are no DJs with character like John Peel or people of that nature who play their own choices. It’s all teams of producers, selection committees, formats. Sad, really. They think ‘You Can Dance’ is ‘specialist’…”

‘You Can Dance’ plays with the list-twist idea of ‘Do The Strand’…

“It’s in that idiom. I’ve been singing it a lot lately, and I can tell I like those lyrics because I’m still enjoying it. If after doing a video for eight hours you aren’t fed up with it, then you must really like it.” The video – the Ferry aesthetic turned up to eleven – was shot in Wiltons Music Hall (“I like old venues that have a bit of history to them”) and the director’s pitch appears to have been, “Wall-to-wall gyrating supermodels, right?” (“As with the cover art, it was: go for broke”). Ferry adds how he loves playing the Olympia Music Hall in Paris, (“Where you feel: Piaf has sung here”) and reckons he was one of the first people to play a rock concert at the Royal Albert Hall (“because I had an orchestra, for my first solo gig for ‘These Foolish Things’, so they let us in…”)

He discusses the Kate Moss cover shot, which extends the proud tradition of Roxy/Ferry album sleeves. “Normally we’d try to choose an unknown as this glamorous icon figure, but this time, why not go for the icon? She’s perfect for this. She has this strength of image, as well as the beauty, to play the Olympia role. Of course the original Manet is a very powerful picture. You come up against that. That’s a picture I remember being very taken by, as an art student. I’d think: how and why is this so strong? It’s all in the eye of the beholder – her arrogance, haughtiness. She’s kind of staring you out: who do you think you are? And yet for its day, it had a kind of, I guess, tartiness, too. Very shocking in its era.”

There were other shots from that session, which we saw at the exhibition, which were less direct, more multivalent…

“Well, yes, we had lots of arguments choosing. By the way we had that big electronic billboard, it’s the biggest one I think, out by Shepherds Bush and the huge roundabout and flyover. For a week. And it was fabulous. It looked really great. I thought it was the best visual thing we’ve ever achieved really. It looked so cool that we drove around the roundabout again and again!”

How very J G Ballard, I mutter perfunctorily, beaten down by years of rock stars not knowing what I’m on about…

“Exactly!” says Ferry happily. “Ballard would have loved it, right there overlooking the Westway. It sets you up for your…lightning drive. The shiny grey steel futurist world.”

You once said you devised your record sleeves, inspired by the Pop Art you’d studied, thinking of the cover girl as the “idealised Roxy fan”. Is that still the case? Would Kate Moss now be your ideal fan?

“I don’t know,” chuckles Ferry, to his credit. “These days you’ve got to take what you get, ha ha. When Roxy started out, obviously the fans were much younger. Your fanbase grows older with you. Although quite often we find their children have got into it. And a lot of bands that they like have maybe mentioned Roxy as an influence. It probably also didn’t do any harm that Avalon, the last record, was the most successful they ever made.” He takes off his sweater. He’s still wearing an immaculate shirt and tie.

I’m interested that he says “they” when referring to Roxy Music, not “we”. It’s time to talk about Roxy. He refers jovially to their festival shows of this year as “the Roxy summer season”. “I’ve got a good Roxy archive forming downstairs now. Generally it’s pretty good to know some of your history is saved. We’ve got a good team here in this building at the moment with lots of young people passing through the portals. How organised the archive is I’m not sure, because I never look at it. There’s one guy down there who’s been working on it for a couple of years. Every few weeks he pops his head out and I ask if he’s all right and he says oh yes, yes…he’s beavering away, I guess.”

Does he have a white labcoat and a wild-eyed stare?

“Yes, possibly. We’re busier here now than I can ever remember. There’s a website now, and that gets taken care of. I mean I come here nearly every day and there’s never enough time to do everything. Since the record finished I’ve been chasing to catch up. Because of course there were the Roxy gigs that I’d promised to do and couldn’t back out of, though it wasn’t convenient. I’d be working on artwork for Olympia then dashing off to Bestival…”

Do you have to switch to another part of your brain to do the Roxy shows?

“Yes, it’s weird. It worked quite well this year. I had them rehearsing for a week before I went the last day, just to see if it was all right. Some of the people are from my solo band; they’ve been drafted into the Roxy militia. And my son Tara has been seconded as additional drummer. My musical director Colin Goode is very good at drilling everybody. I know how to sing the songs, so I just go in and go, yes, that sounds good. It IS fruitful. It was therapeutic to finish the album here and then instantly go onstage with Roxy in front of an audience, because you don’t get a great deal of feedback when you’re making a record. The odd person might pop in, but generally nobody really gets to hear it till the end.”

Do you still reckon there were three distinct Roxy phases? The first being the first two albums with Eno, the second running from Stranded to Siren, the third being the comeback from Manifesto through to Avalon?

“Yes, and the first and third were the most interesting.”

See, here’s where I disagree with the consensus. Stranded (Eno’s favourite, magnanimously), Country Life and Siren are right up there for me.

You were at your most lyrical (in every sense).

“But Stranded belongs to the first phase. It begins phase two, but there’s an overlap. Some of the songs were written earlier. ‘Psalm’ was one of the first I ever wrote. And ‘Mother Of Pearl’ relates to ‘In Every Dream Home A Heartache’… it wouldn’t have felt out of place on For Your Pleasure, for instance. Country Life and Siren are…well, they’re all right.”

Sacrilege! ‘Sentimental Fool’ on Siren is one of your masterpieces. Musically, lyrically, and in the way it seems to have shape-shifted every time I go back to it, I’m hard-pushed to think of six minutes that speak to me more profoundly. How come it gets so overlooked?

“Oh I like that one! It’s a shame we only ever performed it on the Siren tour. It started the show, which was quite brave.” He starts singing the intro to himself. “Yeah… I was quite into that. Maybe we should try to revive that on the tour in the new year…”

When you switch hats to Roxy again…

“Yes… but I’m lucky to have so many hats. Can’t complain! It’s just the voice… it gets quite sore… and I have to do a private charity show tonight…” He waves his arm towards the room. “How do you think I pay for all this?”

The Roxy guys (Manzanera, Mackay, Eno) are on Olympia, yet people moan there’s no “new Roxy album”. Critics seem to fixate on personnel rather than the end result, the back-story rather than the art itself. And it’s forgotten that the early Roxy of yourself and Eno accounted for only about a twentieth of each of your careers. It must be like they’re harping on about a girl you dated at school when you’re on your fourth marriage.

“They do fixate on that, yes. They forget I’ve worked with them on several other albums as well. They’ve made the same sort of guest appearances. It’s very nice to have them there; Phil plays more than the other two. He co-wrote ‘BF Bass (Ode To Olympia)’ but I’m not sure if he likes what I did with it as I haven’t talked to him about it yet. Andy doesn’t play sax, but oboe, just the odd note because it’s such a beautiful distinctive sound. He plays one note on ‘Song To The Siren’, but it’s the perfect note. Eno plays on a few backgrounds; it’s so mixed down though. As you say, people make mountains out of molehills. You know, on… what’s that thing… For Your Pleasure… there’s a guy all over it called John Porter, who nobody ever mentions to this day. He rang me the other month; he’s moved to New Orleans and produces blues albums. His bass lines on For Your Pleasure are so great, yet no-one ever says, ooh, when’s the reunion with John Porter?”

He starts singing the bass line to ‘Do The Strand’. “The bass on Olympia by Marcus Miller is…well, he’s a genius. He understands my music, he gets it. Of course he played with Miles Davis, which isn’t bad. Dave Gilmour came in for one afternoon, plays on two tracks. Nile (Rodgers) played on everything. He kind of took over from my guitarist David Williams, who died, which was incredibly sad. He was part of my gang, one of my mates, y’know? My brother. He’d say, ‘How’re you doin’ my brother?’ Actually he’d say, ‘How’re you doin’ my nigga?’”

“I was shy of collaboration in the past. When you start off your career, it’s always me me me. ‘Oh no, I’ve got plenty of ideas, I don’t need anybody else to interfere.’ If, say, David Bowie had said in ’73, ‘Oh can we write together?’ I’d have said no, I’m not interested.”

What if Bowie said that tomorrow? (This flies out of my mouth with an unpremeditated excess of zeal).

“Ah…that could be…ah, maybe, yeah. I’d be interested in anybody that I liked.” Randomly, he praises Modest Mouse and Arcade Fire. Asked which version of ‘Song To The Siren’ inspired him to interpret it, he says, “I’d never heard the Tim Buckley version until fairly recently. When I made it I’d only heard This Mortal Coil. I remember the video was very pretty and I said, God, that’s a great song, I want to do that one day. It turned into quite an opera really. It was a challenge – the sea, the ocean, whalesong – there are so many different sounds on that.” The vocal is such a deft, understated yet emotive contrast to Liz Fraser’s; it’s one of his best and most astute.

“’Alphaville’ was named after the Godard film which “was a landmark of the Nouvelle Vague when I was at college. It was very cool. It’s an evergreen.” Discussing the album’s finale/postscript ‘Tender Is The Night’, as I bring up F. Scott Fitzgerald-Ferry comparisons, he corrects me on a literary point of order. “Remember Keats used the phrase in a poem first, and Fitzgerald took it from there. I mean I do love Fitzgerald, he was a huge influence on me, but I love the Romantic Poets as well. It’s a lovely phrase. The track drifts off into space, into the ether. I like the radio crackling, scanning in and out as if from a foreign station, which adds to the feel of alienation, of loneliness…” His favourite track is ‘Reason Or Rhyme’, which also wouldn’t have seemed out of place on For Your Pleasure. It’s that good.

Do you feel your music is of today, or timeless?

Long cautious pause. “I’d like to think it’s both, really.”

Last time we spoke you bemoaned the demise of Old Europe, the way the individual countries’ identities are being homogenised into one big American shopping mall. I like to think you love Venice. Maybe you are the Venice of pop music.

“I… was fortunate to be born when I was. To feel different currencies in my hand. Going to Paris is still a treat as I always feel it’s much more feminine than London. They complement each other, in the way that New York and LA do. Of course the French still fiercely hold on to their culture. It’s interesting to look at Spain, or Catalonia – they’re banning bullfighting because maybe they want to feel part of the modern world. I have mixed feelings about that. I like old-fashioned and idiosyncratic things. I like going to Seville, the traditions of Andalucia, the music, the colours. And I like Eastern Europe. I still love travelling a lot, though the work compels you to do it. It’s not as if I have a trusty stick and a knapsack. I’m going to Italy next week. If I go on holiday, that’s where I normally go. I love the food.”

You remain an aficionado of the finer things?

“Oh it doesn’t have to be fancy food. I like more rustic, peasant-y type food. I do like five-star hotels, mind you.”

I’m looking around at all your art now. Some might be surprised that your collection (much admired in art circles) isn’t all Pop Art…

“But that depends where you live. If I had a big loft in New York I like to think I’d have a lot of late 20th century art there. But where I live – I don’t live here, my main house is in the country – contemporary art doesn’t look right.” He gets up, beckons me to follow, and we walk half a mile to the other end of the room. He shows me a French surrealist painting from the 1900s, telling me the name of the artist, but we’re so far away from the tape recorder I can’t tell you it now. We walk by another wall. “Whereas these are more modern, they’re Richard Hamilton…” (famously, Ferry’s art teacher).“And very cool. Context is important. I love different periods of art, just as I love different periods of history. I’m quite fond of the 18th century…”

“Times are hard though,” he muses, controversially. We’re back at our seats. “I don’t store things in chambers like some people do, or horde stuff. If I’ve got an empty wall I’ll put a picture on it. I love decorating houses. It’s my favourite thing. I’m quite good at it. I love fabrics, objects. I suppose, I don’t know why, they become my friends. Ha! They do. They don’t answer back. And they’re just beautiful. I like THINGS. I like people as well… but I probably like things better. Of course they’re made by people, so I suppose it’s the best part of them…”

This makes sense if you consider the magnificent Roxy/Ferry oeuvre to be the distillation of his aesthetic. Even if you’re not a fan of his aesthetic, at least he HAS one. That’s rare nowadays.

“You don’t stop being interested in your aesthetic over the years. You get more and more into it.”

Is your constant pursuit of the beautiful an attempt to escape the everyday and mundane?

I’m momentarily worried he won’t like this question but he quickly says, “Yes. It’s a search for a better world, really.” Then he takes one of his tangents. “I’ve never been that interested in politics. I met this interesting chap yesterday…Andrew Marr? I had to do his show. We did it here. He’s an author too, I think…”

He’s a big Picasso fan/expert.

“Is he really?” His eyes light up. “We got on very well, but I suppose the only aspect of politics I felt able to discuss was political correctness. Because I hate all that kind of thing, when you’ve got to watch what you say. It’s too Kafka for me. It’s just too annoying, you know? And England has become like that.”

Clearly, this is my cue to raise the “Nazi art controversy” incident. He’s still stinging from what he – and for the record, I – perceived as a gross injustice. In 2007 he was hauled across the tabloid coals for praising the beauty of the films of Leni Riefenstahl and the architecture of Albert Speer. Astonishingly, elements of the media considered this (which countless intellectuals and academics echo in universities every day) an offensive statement, wilfully mistaking the aesthetic for the ideological, and Ferry had to tick the modern atonement box of apologising. It got him into big trouble with his American record company.

“It was unbelievable. Yes, I agree, it IS good art, as art. I couldn’t believe the fuss, it was staggering. It led to a lot of grief. My managers, who were Jewish, flew to the States for talks and said this is ridiculous. In fact you can’t like music to the degree that I do without being totally immersed in Jewish culture, and black culture for that matter, whether it’s the songs of Broadway, or jazz, or any of the great strands of American music. I also think art should be allowed to be provocative. And that Speer made some incredible buildings.”

So two separate issues became muddled by a simplistic media?

“Yes. It was a witch-hunt of sorts.”

The heaviest rain of the year starts hammering the high windows. We’re drawing to a close. Why did he act onscreen in Neil Jordan’s Breakfast On Pluto, and never before or since? “That’s the only time I was asked, ha ha! I haven’t turned any roles down, to speak of, and I haven’t looked for any. Cameo roles are OK like that; Tom Waits does it very well. What I’d really like to do is a great soundtrack to a great film. That’s something I’ve under-exploited. My music’s always been very cinematic. Of course you create your own movie in your head to it, but… cinema can be a powerful medium when you get it right. It’s because I’m a singer… maybe people don’t use their imaginations and realise the tracks exist as instrumentals for most of their working lives, and I only sing on them towards the end. Often I think it’s a shame to sing over them really, in case it spoils them.”

The lyrics are always the very last thing?

“Always. Because then you’ve committed and there’s no going back.”

Next for Mr. Ferry come the Roxy dates, at little places like the O2 Arena. The Olympia album, marvellously, bears as a banner the Goethe quote “the eternal feminine leads us on”. Do you feel you’ll keep doing this till you drop? “I’ve been a bit fed up the last few days because my voice has been hurting. What I’ll do next, we’ll see. I’d really like to start something new but I’m committed to the Roxy shows. People describe me as “laid-back” or “cool” but I’m often rather impulsive. Hopefully my music won’t go in or out of fashion again by next week. It is what it is.”

He walks me out. Oh, I go, there’s Warhol’s Chairman Mao. “Yes,” he says, “and oh there’s my Q Icon Award, heh heh.” I emerge blinking into a deluge, and after thirty seconds realise this rain is biblical. I take shelter in a cafe opposite the girls’ school where Bryan Ferry once taught pottery. One of us is back in the real world again.