Janelle Monáe is the new Bowie – or so The Guardian would have it. But it always registers as suspicious when the PR personnel wheel the art-pop colossus out. More often than not it’s spin for some rainbow-chic indie release and, on more than one occasion, a starlet’s directional mishap come album No.3. Also available is the ‘New Kate Bush’ for the wacky gals and ‘New Prince’ for the multi-instrumentalist guys.

Bowie transformed on an album-to-album basis, always with a reverence for the LP as a self-contained statement. Bereft of imagination, idealism or even just a sense of romance, today’s pop shape-shifter has little regard for aesthetic logic. We are expected to swallow Beyonce as the gangsta’s moll, faithful subordinate and sassy post-feminist all within 50 minutes of reel. It has a way of decontextualising the songs – that most alienating sin of manufactured pop. The only thing behind the face is some champagne-popping execs and a big dollar bill. Pop is simultaneously out of control yet inert; a kind of hyperactive stasis.

So, let’s say the industrial revolution replaced everything beautiful with something practical: the proverbial ‘flowers in the dustbin’. In the digital revolution, the first casualty is the artist’s mystique, followed swiftly by the subtext. And it’s here where Janelle Monáe earns her press. The Atlantan is tangible proof that the idea for every great pop icon begins its life as art, and cements the conviction that Bowie’s morphing was in itself genuflection to art as pathway to self-actualisation.

Across an Iliad-esque concept which takes silent-era epic and Marxist allegory Metropolis as a narrative foundation, Monáe has made a conscious effort to restore Afrofuturist cosmology to the forefront of urban contemporary music. Not since RZA’s spirit-world Staten Island has black music produced such a fully-realized example of therapy-by-fantasy as that contained on the cinematic The Archandroid. While Santigold and MIA travel the world plastically atop their magic mixing desk, Monáe only has to relocate to her so-called ‘Palace Of The Dogs’ (a kind of Valhalla for black artists) to assume her multifarious alter-ego. The resultant Afrofuturist ‘E-motion picture’ that underpins her debut is intrinsic to Monáe’s rightful claim as an auteurist pop star with real import. She’s an agent of change, and we’re not just talking robot emancipation here.

‘Slavery stripped blacks of almost every possible form of identity. National, familial, religious, and tribal identity was completely wiped due to the slave trade. At that point, what history do you have left? Not much of one, right?’

Blogger Arri Acornly, Berkely

Where do you go when you don’t have a past? The future.

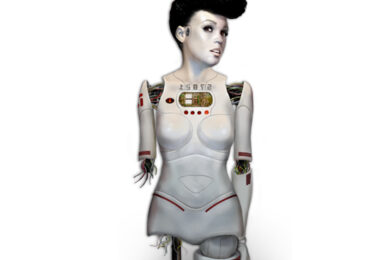

When Andre 3000 imagined himself saved from deep-space lonesomeness by ‘The Prototype’, Janelle Monae was surely what he had in mind as a mock up. On a purely visual level, Monáe sports a protruding afro somewhat like an alien antenna reminiscent of DJ Ruby Rhods’ in The Fifth Element, and in tribute to Metropolis‘ Art Deco milieu she wears a Gatsby-period tux. The garb is simultaneously a nod to ‘post-human’ androgyny and a symbol of class mobility, while her alignment to the 20s holds particular resonance – an era described by social scientist Frederic Jameson as the "last moment in which a genuine American leisure class led an ostentatious public existence, enjoying its privileges without guilt in full view of the other classes". The Egyptian headdress she sports on the cover of The Archandroid (plumed with the copper-green skyscrapers of Metropolis) is in homage to free-jazz pioneer Sun Ra (the moniker ‘Ra’ taken from the eponymous Egyptian sun god), who also declared himself a messianic saviour and whose aesthetic was the first example of a black musician overtly appropriating sci-fi iconography. For him, Sun Ra was an alien abductee – and, through the prism of the African diasporic experience, so was every black American in a literal sense. Meanwhile the Egyptians – an eon-ruling race of beautiful and technologically-advanced African aristocracy – represented supremacy and recaptured empire.

Even pre-dating Sun Ra, glimpses of embryonic Afrofuturism entered black music as far back as a sci-fi infatuated Jimmy Hendrix painting low-flying UFO’s in arching brushstrokes of gain, while in his 1995 essay Black To The Future, Mark Dery cites the techno-psychedelic nature of Dub Reggae’s studio trickery "made out of dark matter and recorded in the crushing gravity field of a black hole". After Sun Ra, the aesthetic was pushed ever further into the mainstream by George Clinton on Parliament’s 1975 album Mothership Connection. A year previously though, drawing from The Stooges’ mechanistic proto-punk, some forward-thinking Germans suddenly presented the Afrofuturists with a very real future.

In the wake of Kraftwerk’s seismic Autobahn, British synth pop and industrial the emerging Detroit techno movement (and laterally New York electro) created a whole new dimension in which Afrofuturism could spread its wings. Again there was a discourse revolving around notions of empowerment. It was the idea of turning white-owned science back on the creators, a political act which Dery calls the "retrofitting, re-functioning and wilful misuse of techno commodities". In fact, Dery’s definition adequately describes the invention of acid house, with its use of a "disposed oddment" in the shape of the Roland TB-303 in ways unintended by its maker. It was this siphoning of the resources prohibited to them by the technological oligarchy which had them cast as cyber-punks, or "techno rebels" as Alvin Toffler theorised in Future Shock.

Secondly, there was the connection between Afrofuturism and class elevation, which again originates with The Belleville Three who reinvented themselves as sleek aristobots, playing to affluent black kids bedecked in chic European clothing brands. Detroit techno engaged with the European sophistication implied by Kraftwerk’s composed minimalism, which was completely drained of the American blues element, yet expressed the melancholy the students felt permeated post-industrial Detroit. It is worthwhile noting that even before the EDM outbreak, disco was repudiated by black funk musicians as synthetic, unnatural and rootless. Subsequently so was its direct descendent – the Moroder-informed Chicago house, itself an ostensibly denatured and bracing variant of the disco genre. More recently, culturalists have alluded to DJ mixing as an extension of Afrofuturism in the way hip-hop DJs use turntable technology and sampling to reposition, decode and reassemble, in uneasy commonality, a half-century’s worth of American narratives: "Travelling by synecdoche," as Afrofuturist devotee and illbient producer DJ Spooky terms it.

The head-spinning genre conflation on The Archandroid is the beachhead of Monae’s Afrofuturism. Speaking with The Quietus about Monáe, Marlo David, Afrofuturist scholar and professor of Woman Studies at Perdue University, points to the ancient tribal ritual of "playing mas"; a febrile act of spiritual rhapsody which involved assuming multiple guises around the fire. It’s the same process that empowers the Afrofuturists to "shift personae in ways that counteract the limitations of identity imposed by the hegemonic gaze of race, gender, class, and religion".

Monáe’s appropriation of the historically ‘non-black’ genres of rock, electronica, MGM musical orchestration, cabaret and folk music allows her to transcend ideological borders – as she told The Quietus, "I learned to embrace things that make me unique even if they make me uncomfortable sometimes". What strikes you most on The Archandroid is Monáe’s impossibly malleable voice which toggles though so many different tones, timbres, modes and methods as to be almost machine-like; or, at least, non-human. It’s the Android 57821 flicking settings on a sternum-embedded control panel, yet organic and native to the 24-year-old’s age-old soul.

While the genre-trekking on The Archandroid plays out in the foreground of some beautiful production, it takes more than special effects to be a bona fide afronaut. After all, with a bit of synth and a green-screen even The Black Eyed Peas can be futuristic, while everyone from the Daft Punk-sampling Kanye West to Martian M.C Lil’ Wayne flirt with Afrofuturist language – verbal or otherwise.

"To me, Janelle Monáe truly captures the idea of Afrofuturistic music," argues David, "which is more than the use of digital technologies, calling yourself an alien or having music filled with blips and glitches or Autotune, although these elements are important". For David, it’s Monáe’s use of both cutting edge production machines and futuristic styles (i.e the ‘non-human’) and her adherence to the like of James Brown and more ripened forms (i.e the ‘human’) which is key. This ‘inexplicable mashup’ – the call-and-response between past and future – is what distinguishes the Afrofuturist from your garden-variety ‘black musician into sci-fi’ and brings to the fore perceptions that African-Americans have always symbolically been human and non-human: "In the era of slavery, people of African descent were human enough to live and love and have culture, but were nonhuman to the extent that they were ‘machines’, labour for capitalism". This duality imposed on them by slavery is what David believes Monáe and other true Afrofuturist artists are confronting. By manipulating these symbolic references of past and future, a kind of third entity emerges which David describes as "a cyborg identity, in resistance to that involuntary binary". Or, as Monáe has it on ‘Cold War’: "I’m another flavour /Something like a terminator".

"In a post-human universe governed by zeroes and ones, the body ceases to matter"

Marlo David

"I’m a cybergirl without a face a heart or a mind,

(a product of the man, I’m a product of the man),

I’m a saviour without a race (without a face)."

Janelle Monáe on ‘Violet Stars Happy Hunting’, from her debut EP ‘The Chase’

Others perceive Afrofuturism as in conflict to the idea of even being human, which music critic Kodwo Eshun describes as a "treacherous category" for the Afrofuturist. If you aren’t human neither can you be "subhuman" or "nonhuman", common descriptions in civilised societies for ‘the other’ i.e the marginalized ethnic classes, the impoverished and the homosexuals – the "semiotic ghosts", as William Gibson saw it. It is part of a rejection of "black humanist" culture in favour of a new subjectivity which jettisons the traditional image of "black bodies in pain" expressed in blues and soul. Thus, if you’re "intergalactic funkadelic" (as George Clinton liked to put it), no longer is ‘the self’ defined reactively by the freedom struggle against white oppressors, who are allowed a presence by inference and thus are free to over-determine African-American culture. As one blogger and Berkeley history graduate Arri Acornly interprets this: "Black women can explore the physical expressions of her feminine form without being sexualised and animalised. A black man can just be a man and not a black man.".

"Eyes look to the moon,

Avoid a world so sad,

Ruled under the hate,

Where there is love."

Janelle Monáe on ‘Babopbyeya’ from The Archandroid

The rebel android Cindy Mayweather is sentenced to retirement for falling in love with a human; a black woman defying societal mores by falling for a white man. As Marlo David tells The Quietus: "Janelle offers her narrative of a futuristic world where certain kinds of love are forbidden, via a simulated or mechanized but still racialized version of her self". This method of projection has a long history in Afro-American culture. "Black people have always been masters of the figurative," writes the prominent black scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. "Saying one thing to mean something quite other has been basic to black survival in oppressive Western cultures."

From chain-gang songs – encrypted condemnation on the jailors – to Chic’s bliss-wrapped afront on Black hedonism, this "metaphorical literacy" is innermost to Black American music. Furthermore is the theme of superhuman customisation, which of course in art is a well-worn act of resistance to limitation. In interviews Monae relates the dystopian cityscapes depicted in Metropolis to the boarded-up projects of poverty-wracked Kansas, while on ‘Cold War’ she constructs the perfect sci-fi metaphor: "Below the ground’s the only place to be/ Because in this life you spend time fighting off the gravity". It’s a common thread in black sci-fi literature – that notion that the frightening future imagined by white sci-fi writers is a reality for the majority of African America; ‘the now’ rather than prophecy. It’s Monae’s android upgrade as Cyndy Mayweather that grants her the means to battle an oppressive regime and liberate the ‘have not’s of society. Consider that the word ‘machine’ is thought by some to be derived from the Greek word for remedy.

Back in the real world, contempt for the fan’s capacity to discern between innovation and re-branding is rife. Neither are we trusted to assimilate anything beyond that of immediate sensation, like maybe a bottled-lighting concept, substituted for whole banks of jobbing outsource producers and star guests. The finished product isn’t ‘multifaceted’ or ‘eclectic’, it’s an exercise in narrowcasting, a portfolio of products, inflationary, shrilly exacting. If every pop star is all things to all people in the space of one release, then what you’re really talking about is the illusion of choice. Follow the money, as they say.

If ever you’ve been pushed to draw the line between ingenious reconstitution and sausage paste, The Archandroid seems every bit the polymorphic quantum leap squabbled over by Rihanna and Lady Gaga. Pop’s greatest art-impostor, Gaga been heralded as everything from feminist icon to master surrealist, and who in musicologist Alexandra Apolloni’s opinion posits the "debilitating burden of fame [and] the stereotype of the female body as both object of desire and a subject of shame and discomfort". High-minded praise indeed for some savvy image hooks, electroclash stage-garb, a piss-poor impression of New York performance art and one woman’s quest to let everyone know she works out. Behold the difference between transgressive and publicity-rigging.

Maybe it has always been this way, and in the final analysis a good tune is paramount. Never, though, has pop felt so recursive, so amnesic, or so self-perpetuating. It’s kind of like that vacuous Lexus car factory in Minority Report, where in near-future industry self-sustaining automatons work tirelessly to make machines of their own.

Although The Archandroid‘s ’60s soul grounding is unlikely to induce the shock of the new, there is a real spirit of effervescent discovery permeating here. And, by unlocking the imagination-firing power of speculative fiction and her own desire for self-determination, Monáe has ushered us towards a hidden escape hatch we forgot was there. Vive La Revolution, Metropolis 2010.