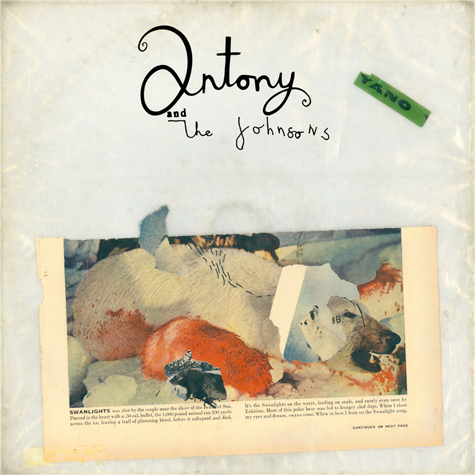

Antony and the Johnsons’ fourth album, Swanlights, is released in October, preceded by an EP at the end of August. It’s being trailed as a lush, verdant contrast to the sparse Crying Light of 2008, partly because that’s how publicity works, but also because it will be available alongside a book containing Antony’s paintings, writing and photography: an expanded, multi-layered experience of Antony Hegarty’s singular world.

I haven’t seen the book; but the music, even as it ripples out into some painterly sounds, textures and moods not found on its predecessors, is thankfully still constructed with the clean lines and simplicity that are at the heart of all Antony’s work. There’s a preconception that his music is ornate, theatrical; close listening often finds it to be quite the opposite, spacious and spare, and crafted with beautiful discipline. Swanlights is only 46-minutes long, and no song outstays its welcome. And they are all songs: for all the many unnecessary words I and other journalists will spin out about the album’s charms – see below: enjoy! – one of the most enduring aspects of Antony and the Johnsons’ music is the primacy and magic of the song as a thing in itself; the reminder that it is sometimes the only form in which to express that which just ends up in a tangle when put into prose.

Everything Is New

A sudden start, the title spoken in wonderment. The title is this song, and not just because "Everything is new" is the only lyric: the melody and arrangement act out the words with diligent clarity. The piano is careful and high in the register as Antony repeats the three words. Boldness and momentum gather, cymbals swarm and strings bolster in preparation for the breaking wave of the song from wonderment into celebration, as Antony bursts into full-throated, wordless lauding, backed by warm brass arrangements.

The Great White Ocean

I’m thinking of Dirty Projectors’ ‘Two Doves’, the intricate folk-pop number voiced by Angel Deradoorian, as I listen to this song. They’re not alike, exactly – aside from being led by a simple acoustic guitar pattern – but both tracks remind me of the gorgeous loneliness of Nico or Sandy Denny, where idiosyncratic voices are isolated within neat arrangements that make their bruised melodies even more poignant. Like many of the folk songs interpreted by Denny, ‘The Great White Ocean’ repeats a simple plea or promise; the comforting guitar line suggests a love song or a lullaby, but Antony’s voice is too ‘other’ for either; he sharpens or twists vowels, hangs tremulous at the end of each line.

Ghost

Antony suddenly confronts a phantom and the album springs into life: "Ghost! Leave from my heart!" Once again we’re in or by water – Swanlights‘ sonic atmosphere is clear and airy, but thematically water is its element, a motif that also recurred throughout The Crying Light. The Michael Nyman-ish piano part flickers, pushed along by clustered strings, as we "chase the river, chase the sunlight" towards, presumably, bliss of some kind, voiced in Antony’s final, ascending "This is your day". There’s something of Scott Walker’s ‘Rosemary’ in ‘Ghost’; the way the Walker song swells from stark, minor key verse to swooning and sensual chorus and then back again (a life interrupted and the song likewise. The two songs’ subject matter is not as far apart as you might think – Walker was never ‘just’ writing about a lonely woman; the tributaries of death and mysteries of the next world are always lapping at his characters’ toes.

I’m In Love

Back in the corporeal, signalled by a muted drum-beat, stand-up bass and percussion. An exotic, twisting melody – brass and wind stabs, and a hint of Hammond organ – frames words about hummingbird kisses and ocean caresses, repeating over and over. Repetition means something different wherever it’s located in music, used for devotion, anger or pleasure, here it sounds faintly sinister. Love is treacherous, sinuous and twisty, makes you free-form sing with pleasure, but is hard to get out of, like a voodoo spell that won’t be broken. I like to imagine Yma Sumac providing imaginary backup vocals on this one.

Violetta

35 seconds long, an instrumental interlude which serves to change the mood once again, prepping us for something sombre ahead.

Swanlights

The title track is built upon unlikely foundations: a distorted, heavily reverbed electric guitar provides a drone that’s broken by resolute piano chords only after three minutes of near-dissonance. The guitar recalls John Martyn, spinning out red-eyed over the dawn with Echoplex on infinite, capturing the dark wordless mystery of ‘Small Hours’; the closest reference from Antony’s own catalogue is The Crying Light‘s ‘Water and Dust’, also based on a drone. But ‘Swanlights’ is far less bleak: for all its sonic haziness, it is a celebratory song, building to almost anthemic heights as it progresses, as if acting as an advocate for dreams, darkness, ambiguity and liminality. The only odd note is sounded when Antony sings "It’s such a mystery to me": this, we already know.

The Spirit Was Gone

A kind of companion-piece to _The Crying Light’s opener, ‘Her Eyes Are Under The Ground’, in which Antony returns again to the separation of soul and body after death; the insoluble, impossibility of dying as perceived by the living. "It’s hard to understand," Antony chimes softly, with knowing understatement, separating the words like a recitation or a prepared platitude (like Billy Mackenzie’s assertion that "We feel for you/Deeply concerned" in the Associates track of the same name), over an delicate, familiar-sounding melody. Antony and the Johnsons have frequently ended live sets with a cover of Lou Reed’s ‘Candy Says’, and ‘The Spirit Was Gone’ is Swanlights‘ closest relative to that strange little song, which, even when drawled by an ironical Lou Reed on Berlin, chills and devastates with its finality.

Thank You For Your Love

Electric piano, drums and horns bloom into a country soul number worthy of cosmic gospel seeress Judee Sill, which ends in a tangle of repetition and near-confusion. Again, Antony uses repetition to great effect: he is one of those musicians able to imbue a musical or lyrical phrase with incremental power, so that as it repeats, the effect is one not of monotony but of alchemical change, of somehow becoming. ‘Thank You For Your Love’ spins out into a frantic, fragmented minimalist outro that makes the ‘thank you’ sound more like a please, illustrating how close the two phrases can be, how gratitude is the hidden reverse of desperate need.

Flétta

Before heading to the internet’s Icelandic/ English dictionaries, I wrote that Bjork’s voice curls and grows upon Antony’s in this song like rust or spores of lichen – turns out that one translation of ‘flétta’ is, in fact, lichen. But the other definition the dictionary gives is plait, twist or braid, which makes more sense, in a way: both singers, with their contrasting and very recognisable voices, here seem to exploit their similarities instead, wrapping around one helix-like, with careful harmonies only disrupted towards the end by Bjork’s percussive rolled ‘rs’ and trademark soars. The effect of the voices is more memorable than the song itself, which is slippery, pretty but slightly elusive; it does, however, have a wonderfully subtle, sudden ending.

Salt Silver Oxygen

A cryptic religious vision – flying horses, a female Christ, the great white ocean of earlier in the record, perhaps the "salt mother" of this song – is expressed in pastoral minimalism familiar to fans of Clogs or British chamber group The North Sea Radio Orchestra. In fact, as if in reference to Antony’s longtime associate David Tibet of Current 93, there’s a kind of British idiom to this odd track, bringing to mind not only Tibet’s own visionary lyrical world but also Ralph Vaughan Williams, Michael Nyman, Welsh painter David Jones, or Shirley Collins’ rendition of folk song ‘Down In Yon Forest’. ‘Salt Silver Oxygen’ deals in the archetypal, but feels coded and personal too, like a fragment from a dream. Stark, strong trombone and trumpet suggest something larger lurking beyond this song, its place in a greater narrative.

Christina’s Farm

Swanlights‘ 7-minute finale, already a live favourite, has a cinematic or painterly feel: its vocal line unfolds like a series of haunting scenes, of doves, owls, white lights, haloes, horses, the Virgin Mary, and a backdrop of wide fields and night-times that recalls the pastoral magic of Joanna Newsom’s ‘Emily’, although you’re also reminded of Talk Talk in the song’s tentative pacing and mournful clarinet. The "everything is new" of the opening track returns in the chorus, and once more the song’s power builds incrementally with repetition: "My face and your face, tenderly renewed”. A cloudy, string-heavy arrangement looms and glows, unrestrained and awe-inspired. ‘Christina’s Farm’ hints at an overarching narrative, perhaps for the whole album, but, like much of Swanlights, it is a song to be experienced, loved, wordlessly understood; but not explained.